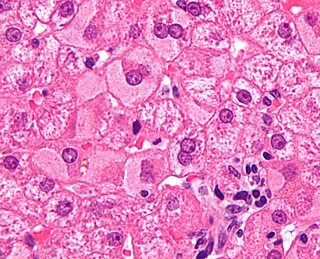

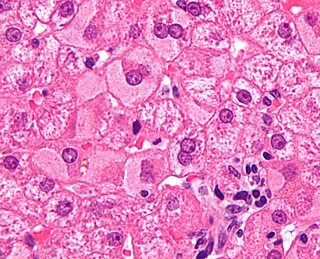

Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver tissue. Some people or animals with hepatitis have no symptoms, whereas others develop yellow discoloration of the skin and whites of the eyes (jaundice), poor appetite, vomiting, tiredness, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Hepatitis is acute if it resolves within six months, and chronic if it lasts longer than six months. Acute hepatitis can resolve on its own, progress to chronic hepatitis, or (rarely) result in acute liver failure. Chronic hepatitis may progress to scarring of the liver (cirrhosis), liver failure, and liver cancer.

Hepatitis C is an infectious disease caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) that primarily affects the liver; it is a type of viral hepatitis. During the initial infection period, people often have mild or no symptoms. Early symptoms can include fever, dark urine, abdominal pain, and yellow tinged skin. The virus persists in the liver, becoming chronic, in about 70% of those initially infected. Early on, chronic infection typically has no symptoms. Over many years however, it often leads to liver disease and occasionally cirrhosis. In some cases, those with cirrhosis will develop serious complications such as liver failure, liver cancer, or dilated blood vessels in the esophagus and stomach.

Hepatitis D is a type of viral hepatitis caused by the hepatitis delta virus (HDV). HDV is one of five known hepatitis viruses: A, B, C, D, and E. HDV is considered to be a satellite because it can propagate only in the presence of the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Transmission of HDV can occur either via simultaneous infection with HBV (coinfection) or superimposed on chronic hepatitis B or hepatitis B carrier state (superinfection).

Viral hepatitis is liver inflammation due to a viral infection. It may present in acute form as a recent infection with relatively rapid onset, or in chronic form, typically progressing from a long-lasting asymptomatic condition up to a decompensated hepatic disease and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Liver disease, or hepatic disease, is any of many diseases of the liver. If long-lasting it is termed chronic liver disease. Although the diseases differ in detail, liver diseases often have features in common.

A satellite is a subviral agent that depends on the coinfection of a host cell with a helper virus for its replication. Satellites can be divided into two major classes: satellite viruses and satellite nucleic acids. Satellite viruses, which are most commonly associated with plants, are also found in mammals, arthropods, and bacteria. They encode structural proteins to enclose their genetic material, which are therefore distinct from the structural proteins of their helper viruses. Satellite nucleic acids, in contrast, do not encode their own structural proteins, but instead are encapsulated by proteins encoded by their helper viruses. The genomes of satellites range upward from 359 nucleotides in length for satellite tobacco ringspot virus RNA (STobRV).

The Jade Ribbon Campaign (JRC) also known as JoinJade, was launched by the Asian Liver Center (ALC) at Stanford University in May 2001 during Asian Pacific American Heritage Month to help spread awareness internationally about hepatitis B (HBV) and liver cancer in Asian and Pacific Islander (API) communities.

In medicine, the window period for a test designed to detect a specific disease is the time between first infection and when the test can reliably detect that infection. In antibody-based testing, the window period is dependent on the time taken for seroconversion.

Hepatitis B is endemic in China. Of the 350 million individuals worldwide infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV), one-third reside in China. As of 2006 China has immunized 11.1 million children in its poorest provinces as part of several programs initiated by the Chinese government and as part of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI). However, the effects of these programs have yet to reach levels of immunization that would limit the spread of hepatitis B effectively.

HBsAg is the surface antigen of the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Its presence in blood indicates existing hepatitis B infection.

Hepatitis B is an infectious disease caused by the Hepatitis B virus (HBV) that affects the liver; it is a type of viral hepatitis. It can cause both acute and chronic infection.

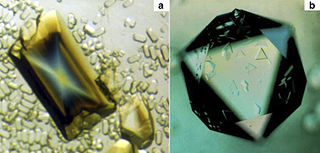

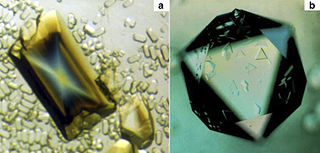

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a partially double-stranded DNA virus, a species of the genus Orthohepadnavirus and a member of the Hepadnaviridae family of viruses. This virus causes the disease hepatitis B.

cccDNA is a special DNA structure that arises during the propagation of some viruses in the cell nucleus and may remain permanently there. It is a double-stranded DNA that originates in a linear form that is ligated by means of DNA ligase to a covalently closed ring. In most cases, transcription of viral DNA can occur from the circular form only. The cccDNA of viruses is also known as episomal DNA or occasionally as a minichromosome.

Estimates place the worldwide risk of cancers from infectious causes at 16.1%. Viral infections are risk factors for cervical cancer, 80% of liver cancers, and 15–20% of the other cancers. This proportion varies in different regions of the world from a high of 32.7% in Sub-Saharan Africa to 3.3% in Australia and New Zealand.

The transmission of hepadnaviruses between their natural hosts, humans, non-human primates, and birds, including intra-species host transmission and cross-species transmission, is a topic of study in virology.

A precore mutant is a variety of hepatitis B virus that does not produce hepatitis B virus e antigen (HBeAg). These mutants are important because infections caused by these viruses are difficult to treat, and can cause infections of prolonged duration and with a higher risk of liver cirrhosis. The mutations are changes in DNA bases from guanine to adenine at base position 1896 (G1896A), and from cytosine to thymine at position 1858 (C1858T) in the precore region of the viral genome.

Mario Rizzetto is an Italian virologist who in 1977 first reported the Hepatitis D virus as a nuclear antigen in patients infected with HBV who had severe liver disease.

Ground squirrel hepatitis virus, abbreviated GSHV, is a partially double-stranded DNA virus that is closely related to human Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and Woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV). It is a member of the family of viruses Hepadnaviridae and the genus Orthohepadnavirus. Like the other members of its family, GSHV has high degree of species and tissue specificity. It was discovered in Beechey ground squirrels, Spermophilus beecheyi, but also infects Arctic ground squirrels, Spermophilus parryi. Commonalities between GSHV and HBV include morphology, DNA polymerase activity in genome repair, cross-reacting viral antigens, and the resulting persistent infection with viral antigen in the blood (antigenemia). As a result, GSHV is used as an experimental model for HBV.

The woolly monkey hepatitis B virus (WMHBV) is a viral species of the Orthohepadnavirus genus of the Hepadnaviridae family. Its natural host is the woolly monkey (Lagothrix), an inhabitant of South America categorized as a New World primate. WMHBV, like other hepatitis viruses, infects the hepatocytes, or liver cells, of its host organism. It can cause hepatitis, liver necrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Because nearly all species of Lagothrix are threatened or endangered, researching and developing a vaccine and/or treatment for WMHBV is important for the protection of the whole woolly monkey genus.

Bulevirtide, sold under the brand name Hepcludex, is an antiviral medication for the treatment of chronic hepatitis D.