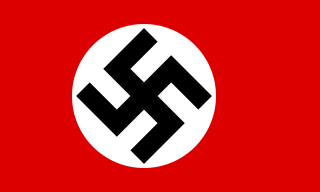

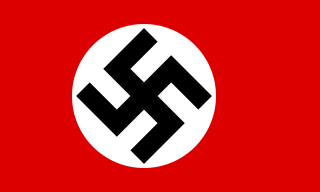

Nazi Germany, also known as the Third Reich and officially the Deutsches Reich until 1943 and Großdeutsches Reich from 1943 to 1945, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party (NSDAP) controlled the country which they transformed into a dictatorship. Under Hitler's rule, Germany became a totalitarian state where nearly all aspects of life were controlled by the government. The Third Reich name, meaning Third Realm or Third Empire, alluded to the Nazis' perception that Nazi Germany was the successor of the earlier Holy Roman (800–1806) and German (1871–1918) empires. The regime ended after the Allies defeated Germany in May 1945, ending World War II in Europe.

The Treaty of Versailles was the most important of the peace treaties that brought World War I to an end. The Treaty ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919 in Versailles, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which had directly led to the war. The other Central Powers on the German side signed separate treaties. Although the armistice, signed on 11 November 1918, ended the actual fighting, it took six months of Allied negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference to conclude the peace treaty. The treaty was registered by the Secretariat of the League of Nations on 21 October 1919.

The Weimar Republic, officially the German Reich and also referred to as the German People's State or simply the German Republic, was the German state from 1918 to 1933. As a term, it is an unofficial historical designation that derives its name from the city of Weimar, where its constitutional assembly first took place. The official name of the republic remained that of the German Reich from the German Empire because of the German tradition of substates. Although commonly translated as "German Empire", Reich here better translates as "realm" in that the term does not necessarily have monarchical connotations in itself. The Reich was changed from a constitutional monarchy into a republic. In English, the country was usually known simply as Germany and the Weimar Republic name became mainstream only in the 1930s.

The Night of the Long Knives, or the Röhm Purge, also called Operation Hummingbird, was a purge that took place in Nazi Germany from June 30 to July 2, 1934. Chancellor Adolf Hitler, urged on by Hermann Göring and Heinrich Himmler, ordered a series of political extrajudicial executions intended to consolidate his power and alleviate the concerns of the German military about the role of Ernst Röhm and the Sturmabteilung (SA), the Nazis' paramilitary organization. Nazi propaganda presented the murders as a preventive measure against an alleged imminent coup by the SA under Röhm – the so-called Röhm Putsch.

Carl von Ossietzky was a German journalist and pacifist. He was the recipient of the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize for his work in exposing the clandestine German re-armament.

Ludwig August Theodor Beck was a German general and Chief of the German General Staff during the early years of the Nazi regime in Germany before World War II. Ludwig Beck never became a member of the Nazi Party, though in the early 1930s he supported Adolf Hitler's forceful denunciation of the Versailles Treaty and his belief in the need for Germany to rearm. Beck had grave misgivings regarding the Nazi demand that all German officers swear an oath of fealty to the person of Hitler in 1934, though he believed that Germany needed strong government and that Hitler could successfully provide this so long as the Führer was influenced by traditional elements within the military rather than by the SA and SS.

The Reichswehr formed the military organisation of Germany from 1919 until 1935, when it was united with the new Wehrmacht.

Der Stahlhelm, Bund der Frontsoldaten, commonly known as Der Stahlhelm, was a German First World War ex-servicemen's organisation existing from 1918 to 1935. It was part of the "Black Reichswehr" and in the late days of the Weimar Republic operated as the paramilitary wing of the Monarchist German National People's Party (DNVP), placed at party gatherings in the position of armed security guards (Saalschutz).

Kurt Ferdinand Friedrich Hermann von Schleicher was a German general and the last Chancellor of Germany during the Weimar Republic. A rival for power with Adolf Hitler, Schleicher was murdered by Hitler's SS during the Night of the Long Knives in 1934.

The events preceding World War II in Europe are closely tied to the bellicosity of Italy, Germany and Japan, as well as the Great Depression. The peace movement led to appeasement and disarmament.

Werner Eduard Fritz von Blomberg was a German General Staff officer, who, after serving at the Western Front during World War I, was appointed chief of the Troop Office during the Weimar Republic and Minister of War and Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces of Nazi Germany and the first general to be promoted to Generalfeldmarschall in 1936. His political opponent Hermann Göring confronted him with criminal records among allegations of pornographic activities of his newly wed wife and forced him to resign on 27 January 1938.

Johannes "Hans" Friedrich Leopold von Seeckt was a German military officer who served as Chief of Staff to August von Mackensen and was a central figure in planning the victories Mackensen achieved for Germany in the east during the First World War.

Paramilitary groups were formed throughout the Weimar Republic in the wake of Germany's defeat in World War I and the ensuing German Revolution. Some were created by political parties to help in recruiting, discipline and in preparation for seizing power. Some were created before World War I. Others were formed by individuals after the war and were called "Freikorps". The party affiliated groups and others were all outside government control, but the Freikorps units were under government control, supply and pay.

These are terms, concepts and ideas that are useful to understanding the political situation in the Weimar Republic. Some are particular to the period and government, while others were just in common usage but have a bearing on the Weimar milieu and political maneuvering.

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) of 18 June 1935 was a naval agreement between the United Kingdom and Germany regulating the size of the Kriegsmarine in relation to the Royal Navy.

A Mefo bill, named after the company Metallurgische Forschungsgesellschaft, was a promissory note used for a system of deferred payment to finance the German rearmament, devised by the German Central Bank President, Hjalmar Schacht, in 1934.

Adolf Hitler's rise to power began in Germany in September 1919 when Hitler joined the political party then known as the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei – DAP. The name was changed in 1920 to the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei – NSDAP. It was anti-Marxist and opposed to the democratic post-war government of the Weimar Republic and the Treaty of Versailles, advocating extreme nationalism and Pan-Germanism as well as virulent anti-Semitism. Hitler attained power in March 1933, after the Reichstag adopted the Enabling Act of 1933 in that month, giving expanded authority. President Paul von Hindenburg had already appointed Hitler as Chancellor on 30 January 1933 after a series of parliamentary elections and associated backroom intrigues. The Enabling Act—when used ruthlessly and with authority—virtually assured that Hitler could thereafter constitutionally exercise dictatorial power without legal objection.

MEFO was the more common abbreviation for, a dummy company set up by the Nazi German government to finance the German re-armament effort in the years prior to World War II.

The German economy, like those of many other western nations, suffered the effects of the Great Depression with unemployment soaring around the Wall Street Crash of 1929. When Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in 1933, he introduced policies aimed at improving the economy. The changes included privatization of state industries, autarky, and tariffs on imports. Although weekly earnings increased by 19% in real terms in the period between 1932 and 1938, average working hours had also risen to approximately 60 per week by 1939. Furthermore, reduced foreign trade meant rationing in consumer goods like poultry, fruit, and clothing for many Germans.

National Socialism, more commonly known as Nazism, is the ideology and practices associated with the Nazi Party—officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party —in Nazi Germany, and of other far-right groups with similar ideas and aims.