| Seminal vesicle | |

|---|---|

Cross-section of the lower abdomen in a male, showing parts of the urinary tract and male reproductive system, with the seminal vesicles seen top right | |

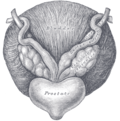

The seminal vesicles seen near the prostate, viewed from in front and above. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Mesonephric ducts |

| System | Male reproductive system |

| Artery | Inferior vesical artery, middle rectal artery |

| Lymph | External iliac lymph nodes, internal iliac lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | vesiculae seminales, glandulae vesiculosae |

| MeSH | D012669 |

| TA98 | A09.3.06.001 |

| TA2 | 3631 |

| FMA | 19386 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The seminal vesicles (also called vesicular glands [1] or seminal glands) are a pair of convoluted tubular accessory glands that lie behind the urinary bladder of male mammals. They secrete fluid that largely composes the semen.

Contents

- Structure

- Development

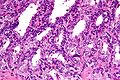

- Microanatomy

- Function

- Clinical significance

- Disease

- Investigations

- Other animals

- History

- Additional images

- See also

- References

- External links

The vesicles are 5–10 cm in size, 3–5 cm in diameter, and are located between the bladder and the rectum. They have multiple outpouchings, which contain secretory glands, which join together with the vasa deferentia at the ejaculatory ducts. They receive blood from the vesiculodeferential artery, and drain into the vesiculodeferential veins. The glands are lined with column-shaped and cuboidal cells. The vesicles are present in many groups of mammals, but not marsupials, monotremes or carnivores[ citation needed ].

Inflammation of the seminal vesicles is called seminal vesiculitis and most often is due to bacterial infection as a result of a sexually transmitted infection or following a surgical procedure. Seminal vesiculitis can cause pain in the lower abdomen, scrotum, penis or peritoneum, painful ejaculation, and blood in the semen. It is usually treated with antibiotics, although may require surgical drainage in complicated cases. Other conditions may affect the vesicles, including congenital abnormalities such as failure or incomplete formation, and, uncommonly, tumours.

The seminal vesicles have been described as early as the second century AD by Galen, although the vesicles only received their name much later, as they were initially described using the term from which the word prostate is derived.