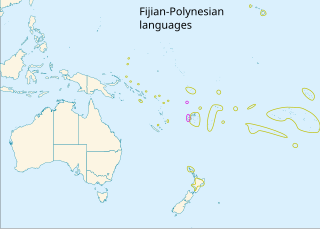

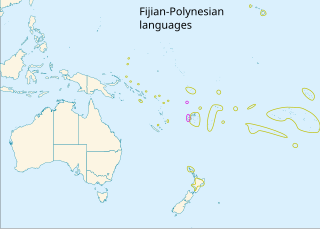

The Polynesian languages form a genealogical group of languages, itself part of the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian family.

Mam is a Mayan language spoken by about half a million Mam people in the Guatemalan departments of Quetzaltenango, Huehuetenango, San Marcos, and Retalhuleu, and the Mexican states of Campeche and Chiapas. Thousands more make up a Mam diaspora throughout the United States and Mexico, with notable populations living in Oakland, California and Washington, D.C. The most extensive Mam grammar is Nora C. England's A grammar of Mam, a Mayan language (1983), which is based on the San Ildefonso Ixtahuacán dialect of Huehuetenango Department.

Kapampangan, Capampáñgan, or Pampangan, is an Austronesian language, and one of the eight major languages of the Philippines. It is the primary and predominant language of the entire province of Pampanga and southern Tarlac, on the southern part of Luzon's central plains geographic region, where the Kapampangan ethnic group resides. Kapampangan is also spoken in northeastern Bataan, as well as in the provinces of Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, and Zambales that border Pampanga. It is further spoken as a second language by a few Aeta groups in the southern part of Central Luzon. The language is known honorifically as Amánung Sísuan.

In grammar, a reflexive verb is, loosely, a verb whose direct object is the same as its subject, for example, "I wash myself". More generally, a reflexive verb has the same semantic agent and patient. For example, the English verb to perjure is reflexive, since one can only perjure oneself. In a wider sense, the term refers to any verb form whose grammatical object is a reflexive pronoun, regardless of semantics; such verbs are also more broadly referred to as pronominal verbs, especially in the grammar of the Romance languages. Other kinds of pronominal verbs are reciprocal, passive, subjective, and idiomatic. The presence of the reflexive pronoun changes the meaning of a verb, e.g., Spanish abonar'to pay', abonarse'to subscribe'.

Tzeltal or Tseltal is a Mayan language spoken in the Mexican state of Chiapas, mostly in the municipalities of Ocosingo, Altamirano, Huixtán, Tenejapa, Yajalón, Chanal, Sitalá, Amatenango del Valle, Socoltenango, Las Rosas, Chilón, San Juan Cancuc, San Cristóbal de las Casas and Oxchuc. Tzeltal is one of many Mayan languages spoken near this eastern region of Chiapas, including Tzotzil, Chʼol, and Tojolabʼal, among others. There is also a small Tzeltal diaspora in other parts of Mexico and the United States, primarily as a result of unfavorable economic conditions in Chiapas.

Alyutor or Alutor is a language of Russia that belongs to the Chukotkan branch of the Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages, by the Alyutors. It is moribund, as only 25 speakers were reported in the 2010 Russian census.

Wallisian, or ʻUvean, is the Polynesian language spoken on Wallis Island. The language is also known as East Uvean to distinguish it from the related West Uvean language spoken on the outlier island of Ouvéa near New Caledonia. The latter island was colonised from Wallis Island in the 18th century.

Futuna-Aniwa is a language spoken in the Tafea Province of Vanuatu on the outlier islands of Futuna and Aniwa. The language has approximately 1,500 speakers. It is a Polynesian language, part of the Austronesian language family.

Tsez, also known as Dido, is a Northeast Caucasian language with about 15,000 speakers spoken by the Tsez, a Muslim people in the mountainous Tsunta District of southwestern Dagestan in Russia. The name is said to derive from the Tsez word for 'eagle', but this is most likely a folk etymology. The name Dido is derived from the Georgian word დიდი, meaning 'big'.

Tsimshian, known by its speakers as Sm'algya̱x, is a dialect of the Tsimshian language spoken in northwestern British Columbia and southeastern Alaska. Sm'algya̱x means literally "real or true language."

Classical Kʼicheʼ was an ancestral form of today's Kʼicheʼ language, which was spoken in the highland regions of Guatemala around the time of the 16th-century Spanish conquest of Guatemala. Classical Kʼicheʼ has been preserved in a number of historical Mesoamerican documents, lineage histories, missionary texts, and dictionaries. Most famously, it is the language in which the renowned highland Maya mythological and historical narrative Popol Vuh is written. Another historical text of partly similar content is the Título de Totonicapán.

Wagiman, also spelt Wageman, Wakiman, Wogeman, and other variants, is a near-extinct Aboriginal Australian language spoken by a small number of Wagiman people in and around Pine Creek, in the Katherine Region of the Northern Territory.

Kanamarí, or Katukina-Kanamari, is a Katukinan language spoken by about 650 individuals in Amazonas, Brazil. It is considered endangered.

Maliseet-Passamaquoddy is an endangered Algonquian language spoken by the Wolastoqey and Passamaquoddy peoples along both sides of the border between Maine in the United States and New Brunswick, Canada. The language consists of two major dialects: Maliseet, which is mainly spoken in the Saint John River Valley in New Brunswick; and Passamaquoddy, spoken mostly in the St. Croix River Valley of eastern Maine. However, the two dialects differ only slightly, mainly in their phonology. The indigenous people widely spoke Maliseet-Passamaquoddy in these areas until around the post-World War II era when changes in the education system and increased marriage outside of the speech community caused a large decrease in the number of children who learned or regularly used the language. As a result, in both Canada and the U.S. today, there are only 600 speakers of both dialects, and most speakers are older adults. Although the majority of younger people cannot speak the language, there is growing interest in teaching the language in community classes and in some schools.

The Nias language is an Austronesian language spoken on Nias Island and the Batu Islands off the west coast of Sumatra in Indonesia. It is known as Li Niha by its native speakers. It belongs to the Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands subgroup which also includes Mentawai and the Batak languages. It had about 770,000 speakers in 2000. There are three main dialects: northern, central and southern. It is an open-syllable language, which means there are no syllable-final consonants.

The Yukulta language, also spelt Yugulda, Yokula, Yukala, Jugula, and Jakula, and also known as Ganggalidda, is a Tangkic language spoken in Queensland and Northern Territory, Australia. It was spoken by the Yukulta people, whose traditional lands lie on the southern coast of the Gulf of Carpentaria.

The Hawu language is the language of the Savu people of Savu Island in Indonesia and of Raijua Island off the western tip of Savu. Hawu has been referred to by a variety of names such as Havu, Savu, Sabu, Sawu, and is known to outsiders as Savu or Sabu. Hawu belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family, and is most closely related to Dhao and the languages of Sumba. Dhao was once considered a dialect of Hawu, but the two languages are not mutually intelligible.

Akuntsu is a Tupian language of Brazil. Peaceful contact with the Akuntsu people was only made in 1995; they had been massacred by cattle ranchers in the 1980s.

Xârâcùù, or Canala, is an Oceanic language spoken in New Caledonia. It has about 5,000 speakers. Xârâcùù is most commonly spoken in the south Central area of New Caledonia in and around the city of Canala and the municipalities of Canala, Thio, and Boulouparis.

Claire Moyse-Faurie is a French linguist specializing in Oceanic languages, in particular the languages of Wallis and Futuna and of New Caledonia.