Related Research Articles

Fijian is an Austronesian language of the Malayo-Polynesian family spoken by some 350,000–450,000 ethnic Fijians as a native language. The 2013 Constitution established Fijian as an official language of Fiji, along with English and Fiji Hindi and there is discussion about establishing it as the "national language". Fijian is a VOS language.

Greenlandic is an Eskimo–Aleut language with about 57,000 speakers, mostly Greenlandic Inuit in Greenland. It is closely related to the Inuit languages in Canada such as Inuktitut. It is the most widely spoken Eskimo–Aleut language. In June 2009, the government of Greenland, the Naalakkersuisut, made Greenlandic the sole official language of the autonomous territory, to strengthen it in the face of competition from the colonial language, Danish. The main variety is Kalaallisut, or West Greenlandic. The second variety is Tunumiit oraasiat, or East Greenlandic. The language of the Inughuit of Greenland, Inuktun or Polar Eskimo, is a recent arrival and a dialect of Inuktitut.

Rapa Nui or Rapanui, also known as Pascuan or Pascuense, is an Eastern Polynesian language of the Austronesian language family. It is spoken on Easter Island, also known as Rapa Nui.

Vaeakau-Taumako is a Polynesian language spoken in some of the Reef Islands as well as in the Taumako Islands in the Temotu province of Solomon Islands.

Taba is a Malayo-Polynesian language of the South Halmahera–West New Guinea group. It is spoken mostly on the islands of Makian, Kayoa and southern Halmahera in North Maluku province of Indonesia by about 20,000 people.

The Nafsan language, also known as South Efate or Erakor, is a Southern Oceanic language spoken on the island of Efate in central Vanuatu. As of 2005, there are approximately 6,000 speakers who live in coastal villages from Pango to Eton. The language's grammar has been studied by Nick Thieberger, who has produced a book of stories and a dictionary of the language.

Sherpa is a Tibetic language spoken in Nepal and the Indian state of Sikkim, mainly by the Sherpa. The majority speakers of the Sherpa language live in the Khumbu region of Nepal, spanning from the Chinese (Tibetan) border in the east to the Bhotekosi River in the west. About 127,000 speakers live in Nepal, some 16,000 in Sikkim, India (2011), and some 800 in the Tibetan Autonomous Region (1994). Sherpa is a subject-object-verb (SOV) language. Sherpa is predominantly a spoken language, although it is occasionally written using either the Devanagari or Tibetan script.

In linguistic typology, a verb–object–subject or verb–object–agent language, which is commonly abbreviated VOS or VOA, is one in which most sentences arrange their elements in that order. That would be the equivalent in English to "Ate oranges Sam." The relatively rare default word order accounts for only 3% of the world's languages. It is the fourth-most common default word order among the world's languages out of the six. It is a more common default permutation than OVS and OSV but is significantly rarer than SOV, SVO, and VSO. Families in which all or many of their languages are VOS include the following:

Tamambo, or Malo, is an Oceanic language spoken by 4,000 people on Malo and nearby islands in Vanuatu. It is one of the most conservative Southern Oceanic languages.

Apma is the language of central Pentecost island in Vanuatu. Apma is an Oceanic language. Within Vanuatu it sits between North Vanuatu and Central Vanuatu languages, and combines features of both groups.

Anejom̃ or Aneityum is an Oceanic language spoken by 900 people on Aneityum Island, Vanuatu. It is the only indigenous language of Aneityum.

The Southern, Kolyma or Forest Yukaghir language is one of two extant Yukaghir languages.

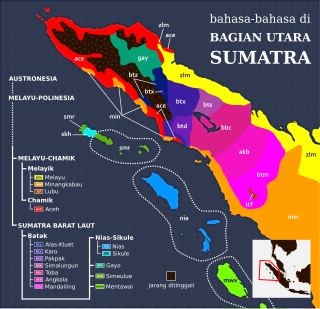

The Nias language is an Austronesian language spoken on Nias Island and the Batu Islands off the west coast of Sumatra in Indonesia. It is known as Li Niha by its native speakers. It belongs to the Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands subgroup which also includes Mentawai and the Batak languages. It had about 770,000 speakers in 2000. There are three main dialects: northern, central and southern. It is an open-syllable language, which means there are no syllable-final consonants.

Uyghur is a Turkic language spoken mostly in the west of China.

Miluk, also known as Lower Coquille from its location, is one of two Coosan languages. It shares more than half of its vocabulary with Coos proper (Hanis), though these are not always obvious, and grammatical differences cause the two languages to look quite different. Miluk started being displaced by Athabascan in the late 18th century, and many Miluk shifted to Athabascan and Hanis.

Mav̋ea is an Oceanic language spoken on Mavea Island in Vanuatu, off the eastern coast of Espiritu Santo. It belongs to the North–Central Vanuatu linkage of Southern Oceanic. The total population of the island is approximately 172, with only 34 fluent speakers of the Mav̋ea language reported in 2008.

Toʼabaita, also known as Toqabaqita, Toʼambaita, Malu and Maluʼu, is a language spoken by the people living at the north-western tip of Malaita Island, of South Eastern Solomon Islands. Toʼabaita is an Austronesian language.

Merei or Malmariv is an Oceanic language spoken in north central Espiritu Santo Island in Vanuatu.

Baluan-Pam is an Oceanic language of Manus Province, Papua New Guinea. It is spoken on Baluan Island and on nearby Pam Island. The number of speakers, according to the latest estimate based on the 2000 Census, is 2,000. Speakers on Baluan Island prefer to refer to their language with its native name Paluai.

Longgu (Logu) is a Southeast Solomonic language of Guadalcanal, but originally from Malaita.

References

- Chowning, Ann; Goodenough, Ward H. (2016). A Dictionary of the Lakalai (Nakanai) Language of New Britain, Papua New Guinea. Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics. hdl: 1885/107217 . ISBN 9781922185310.

- Johnston, Raymond L. (1978). Nakanai Syntax (PhD thesis). Australian National University. doi: 10.25911/5D763637B41D4 . hdl: 1885/10920 .

- Johnston, Raymond L. (1980). Nakanai of New Britain: The Grammar of an Oceanic Language Series. Pacific Linguistics Series B-70. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. doi: 10.15144/PL-B70 . hdl: 1885/148444 .

- Spaelti, Philip (1997). Dimensions of Variation in Multi-Pattern Reduplication (PhD thesis). University of California, Santa Cruz. doi: 10.7282/T3NV9H3K .