Baal, or Baʽal, was a title and honorific meaning "owner", "lord" in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during antiquity. From its use among people, it came to be applied to gods. Scholars previously associated the theonym with solar cults and with a variety of unrelated patron deities but inscriptions have shown that the name Ba'al was particularly associated with the storm and fertility god Hadad and his local manifestations.

ʼĒl is a Northwest Semitic word meaning "god" or "deity", or referring to any one of multiple major ancient Near Eastern deities. A rarer form, ʼila, represents the predicate form in Old Akkadian and in Amorite. The word is derived from the Proto-Semitic *ʔil-, meaning "god".

Qetesh was a goddess who was incorporated into the ancient Egyptian religion in the late Bronze Age. Her name was likely developed by the Egyptians based on the Semitic root Q-D-Š meaning 'holy' or 'blessed,' attested as a title of El and possibly Athirat and a further independent deity in texts from Ugarit.

Hadad, Adad, Haddad or Iškur (Sumerian) was the storm and rain god in the Canaanite and ancient Mesopotamian religions. He was attested in Ebla as "Hadda" in c. 2500 BCE. From the Levant, Hadad was introduced to Mesopotamia by the Amorites, where he became known as the Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) god Adad. Adad and Iškur are usually written with the logogram 𒀭𒅎dIM—the same symbol used for the Hurrian god Teshub. Hadad was also called Pidar, Rapiu, Baal-Zephon, or often simply Baʿal (Lord), but this title was also used for other gods. The bull was the symbolic animal of Hadad. He appeared bearded, often holding a club and thunderbolt while wearing a bull-horned headdress. Hadad was equated with the Greek god Zeus; the Roman god Jupiter, as Jupiter Dolichenus; the Hittite storm-god Teshub; the Egyptian god Set.

Dagon, or more accurately Dagan, was a god worshiped in ancient Syria across the middle of the Euphrates, with primary temples located Tuttul and Terqa, though many attestations of his cult come from cities such as Mari and Emar as well. In settlements situated in the upper Euphrates area he was regarded as the "father of gods" similar to Mesopotamian Enlil or Hurrian Kumarbi, as well as a lord of the land, a god of prosperity, and a source of royal legitimacy. A large number of theophoric names, both masculine and feminine, attests that he was a popular deity. He was also worshiped further east, in Mesopotamia, where many rulers regarded him as the god capable of granting them kingship over the western areas.

Atargatis or Ataratheh was the chief goddess of northern Syria in Classical antiquity. Ctesias also used the name Derketo for her, and the Romans called her Dea Syria, or in one word Deasura. Primarily she was a goddess of fertility, but, as the baalat ("mistress") of her city and people she was also responsible for their protection and well-being. Her chief sanctuary was at Hierapolis, modern Manbij, northeast of Aleppo, Syria.

Ugarit was an ancient port city in northern Syria, in the outskirts of modern Latakia, discovered by accident in 1928 together with the Ugaritic texts. Its ruins are often called Ras Shamra after the headland where they lie.

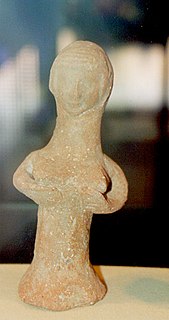

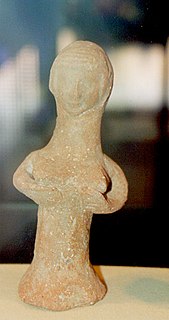

Asherah, in ancient Semitic religion, is a mother goddess who appears in a number of ancient sources. She appears in Akkadian writings by the name of Ašratu(m), and in Hittite writings as Aserdu(s) or Asertu(s). Asherah is generally considered identical with the Ugaritic goddess ʾAṯiratu.

Astarte is the Hellenized form of the Ancient Near Eastern goddess Ashtart or Athtart, a deity closely related to Ishtar, worshipped from the Bronze Age through classical antiquity. The name is particularly associated with her worship in the ancient Levant among the Canaanites and Phoenicians, though she was originally associated with Amorite cities like Ugarit and Emar, as well as Mari and Ebla. She was also celebrated in Egypt, especially during the reign of the Ramessides, following the importation of foreign cults there. Phoenicians introduced her cult in their colonies on the Iberian Peninsula.

Anat, Anatu, classically Anath is a major northwest Semitic goddess. Her attributes vary widely among different cultures and over time, and even within particular myths. She likely heavily influenced the character of the Greek goddess Athena.

Mot was the ancient Canaanite god of death and the Underworld. He was worshipped by the people of Ugarit, and by the Phoenicians. The main source of information about his role in Canaanite mythology comes from the texts discovered at Ugarit, but he is also mentioned in the surviving fragments of Philo of Byblos's Greek translation of the writings of the Phoenician Sanchuniathon and also in various books of the Old Testament.

Idolatry in Judaism is prohibited. Judaism holds that idolatry is not limited to the worship of an idol itself, but also worship involving any artistic representations of God. The prohibition is epitomized by the first two "words" of the decalogue: I am the Lord thy God, Thou shalt have no other gods before me, and Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.

Ancient Semitic religion encompasses the polytheistic religions of the Semitic peoples from the ancient Near East and Northeast Africa. Since the term Semitic itself represents a rough category when referring to cultures, as opposed to languages, the definitive bounds of the term "ancient Semitic religion" are only approximate.

Yam is the god of the sea in the Canaanite pantheon. He takes the role of the adversary of Baal in the Ugaritic Baal Cycle.

Kothar-wa-Khasis is an Ugaritic god whose name means "Skillful-and-Wise" or "Adroit-and-Perceptive" or "Deft-and-Clever". Another of his names, Hayyan hrs yd means "Deft-with-both-hands" or "of skillful hands. Kothar is smith, craftsman, engineer, architect, and inventor. He is also a soothsayer and magician, creating sacred words and incantations, in part because there is an association in many cultures of metalworking deities with magic. The divine name Ka-sha-lu in texts from Ebla suggests that he was known in Syria as early as the late third millennium BCE.

The Baal Cycle is an Ugaritic cycle of stories about the Canaanite god Baʿal, a storm god associated with fertility. It is one of the Ugarit texts.

Baalshamin, also called Baal Shamem and Baal Shamaim, was a Northwest Semitic god and a title applied to different gods at different places or times in ancient Middle Eastern inscriptions, especially in Canaan/Phoenicia and Syria. The title was most often applied to Hadad, who is also often titled just Ba‘al. Baalshamin was one of the two supreme gods and the sky god of pre-Islamic Palmyra in ancient Syria. There his attributes were the eagle and the lightning bolt, and he perhaps formed a triad with the lunar god Aglibol and the sun god Malakbel.

The Early History of God: Yahweh and Other Deities in Ancient Israel is a book on the history of ancient Israelite religion by Mark S. Smith, Skirball Professor of Bible and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at New York University. The revised 2002 edition contains revisions to the original 1990 edition in light of intervening archaeological finds and studies.

Shapash, alternatively written as Shapshu or Shapsh, was a Canaanite sun goddess. She also served as the royal messenger of the high god El, her probable father. Her most common epithets in the Ugaritic corpus are nrt 'ilm špš, rbt špš, and špš 'lm. In the pantheon lists KTU 1.118 and 1.148, Shapash is equated with the Akkadian dšamaš.

Yahwism is the name given by modern scholars to the religion of ancient Israel. Yahwism was polytheistic, with a plethora of gods and goddesses. Heading the pantheon was Yahweh, with his consort, the goddess Asherah; below them were second-tier gods and goddesses such as Baal, Shamash, Yarikh, Mot, and Astarte, all of whom had their own priests and prophets and numbered royalty among their devotees, and a third and fourth tier of minor divine beings, including the mal'ak, the messengers of the higher gods, who in later times became the angels of Christianity, Judaism and Islam.