History of the Pacific Islands covers the history of the islands in the Pacific Ocean.

Hina is the name assigned to a number of Polynesian deities. The name Hina usually relates to a powerful female force who has dominion over a specific entity. Some variations of the name Hina include Sina, Hanaiakamalama, and Ina. Even within a single culture, Hina could refer to multiple goddesses and the distinction between the different identities are not always clear. In Hawaiian mythology, the name is usually paired with words which explain or identify the goddess and her power such as Hina-puku-iʻa (Hina-gathering-seafood) the goddess of fishermen, and Hina-ʻopu-hala-koʻa who gave birth to all reef life.

In Māori mythology, Tāne is the god of forests and of birds, and the son of Ranginui and Papatūānuku, the sky father and the earth mother, who used to lie in a tight embrace where their many children lived in the darkness between them.

Tangaroa is the great atua of the sea, lakes, rivers, and creatures that live within them, especially fish, in Māori mythology. As Tangaroa-whakamau-tai he exercises control over the tides. He is sometimes depicted as a whale.

Atua are the gods and spirits of the Polynesian peoples such as the Māori or the Hawaiians ; the Polynesian word literally means "power" or "strength" and so the concept is similar to that of mana. Today, it is also used for the monotheistic conception of God. Especially powerful atua included:

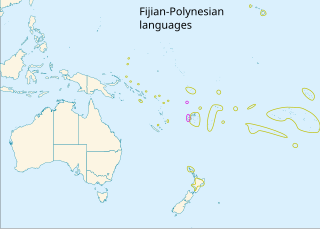

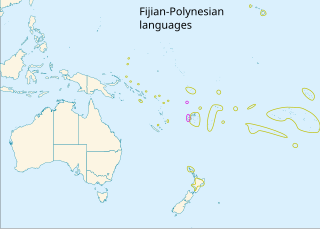

The Polynesian languages form a genealogical group of languages, itself part of the Oceanic branch of the Austronesian family.

In Polynesian mythology, Hawaiki is the original home of the Polynesians, before dispersal across Polynesia. It also features as the underworld in many Māori stories.

The Polynesian Triangle is a region of the Pacific Ocean with three island groups at its corners: Hawai‘i, Easter Island and New Zealand (Aotearoa). It is often used as a simple way to define Polynesia.

Mangareva is the central and largest island of the Gambier Islands in French Polynesia. It is surrounded by smaller islands: Taravai in the southwest, Aukena and Akamaru in the southeast, and islands in the north. Mangareva has a permanent population of 1,239 (2012) and the largest village on the island, Rikitea, is the chief town of the Gambier Islands.

Polynesian culture is the culture of the indigenous peoples of Polynesia who share common traits in language, customs and society. The development of Polynesian culture is typically divided into four different historical eras:

Sir Peter Henry Buck, also known as Te Rangi Hīroa or Te Rangihīroa, was a New Zealand doctor, military leader, health administrator, politician, anthropologist and museum director. He was a prominent member of Ngāti Mutunga, his mother's Māori iwi.

Various Māori traditions recount how their ancestors set out from their homeland in waka hourua, large twin-hulled ocean-going canoes (waka). Some of these traditions name a mythical homeland called Hawaiki.

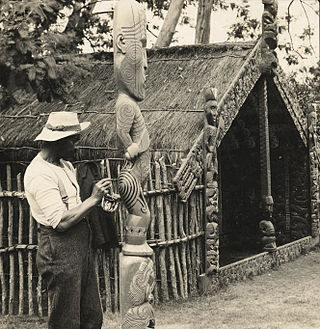

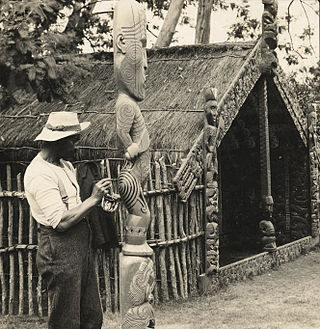

In Māori mythology, Tiki is the first man created by either Tūmatauenga or Tāne. He found the first woman, Marikoriko, in a pond; she seduced him and he became the father of Hine-kau-ataata. By extension, a tiki is a large or small wooden, pounamu or stone carving in humanoid form, notably worn on the neck as a hei-tiki, although this is a somewhat archaic usage in the Māori language. Hei-tiki are often considered taonga, especially if they are older and have been passed down throughout multiple generations. Carvings similar to ngā tiki and coming to represent deified ancestors are found in most Polynesian cultures. They often serve to mark the boundaries of sacred or significant sites. In the Western world, Tiki culture, a movement inspired by various Pacific cultures, has become popular in the 20th and 21st centuries; this has proven controversial, however, as the movement is regarded by many Polynesians as cultural appropriation.

Māori mythology and Māori traditions are two major categories into which the remote oral history of New Zealand's Māori may be divided. Māori myths concern fantastic tales relating to the origins of what was the observable world for the pre-European Māori, often involving gods and demigods. Māori tradition concerns more folkloric legends often involving historical or semi-historical forebears. Both categories merge in whakapapa to explain the overall origin of the Māori and their connections to the world which they lived in.

Rakahanga-Manihiki is a Cook Islands Maori dialectal variant belonging to the Polynesian language family, spoken by about 2500 people on Rakahanga and Manihiki Islands and another 2500 in other countries, mostly New Zealand and Australia. Wurm and Hattori consider Rakahanga-Manihiki as a distinct language with "limited intelligibility with Rarotongan". According to the New Zealand Maori anthropologist Te Rangi Hīroa who spent a few days on Rakahanga in the years 1920, "the language is a pleasing dialect and has closer affinities with [New Zealand] Maori than with the dialects of Tongareva, Tahiti, and the Cook Islands"

Pili line was a royal house in ancient Hawaii that ruled over the island of Hawaiʻi with deep roots in the history of Samoa and possibly beyond further to the west, Ao-Po, in Pulotu, the Samoan Underworld. It was founded on unknown date by King Pilikaʻaiea (Pili), who either was born in or came from either Upolu, Samoa or Uporu, Tahiti, but came to Hawaii and established his own dynasty of kings (Aliʻi). The overall arc of his career describes a brilliant young chief from foreign lands who was eager to share his abundant knowledge of advanced technology with distant frontier rustics. Some stories relate how his ambition got the better of him and damaged his relationships with his subjects. These stories cast him as a libidinous, restless and petty tyrant ever on the move searching for new conquests.

Polynesia is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in common, including language relatedness, cultural practices, and traditional beliefs. In centuries past, they had a strong shared tradition of sailing and using stars to navigate at night. The largest country in Polynesia is New Zealand.

The Polynesian Leaders Group (PLG) is an international governmental cooperation group bringing together four independent countries and eight self-governing territories in Polynesia.

Hina-Oio is a goddess of the sea animals in the mythology of Easter Island. She was married to Atua-Metua and represented the mother of all animals of the sea.

Toi-te-huatahi, also known as Toi and Toi-kai-rākau, is a legendary Māori tupuna (ancestor) of many Māori iwi (tribes) from the Bay of Plenty area, including Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Te Rangi and Ngāi Tūhoe. The Bay of Plenty's name in te reo Māori, Te Moana-a-Toi, references Toi-te-huatahi.