Karen Georgievich Shakhnazarov is a Soviet and Russian filmmaker, producer, and screenwriter. He became the director general of Mosfilm in 1998.

The ribbon of Saint George is a Russian military symbol consisting of a black and orange bicolour pattern, with three black and two orange stripes.

The German Strafgesetzbuch in section § 86a outlaws use of symbols of "unconstitutional organizations" and terrorism outside the contexts of "art or science, research or teaching". The law does not name the individual symbols to be outlawed, and there is no official exhaustive list. However, the law has primarily been used to supress fascist, Nazi, communist, Islamic extremist and Russian militarist symbols. The law, adopted during the Cold War, most notably affected the Communist Party of Germany, which was banned as unconstitutional in 1956; the Socialist Reich Party, which was banned in 1952; and several small far-right parties.

Opposition to the government of President Vladimir Putin in Russia, commonly referred to as the Russian opposition, can be divided between the parliamentary opposition parties in the State Duma and the various non-systemic opposition organizations. While the former are largely viewed as being more or less loyal to the government and Putin, the latter oppose the government and are mostly unrepresented in government bodies. According to Russian NGO Levada Center, about 15% of the Russian population disapproved of Putin in the beginning of 2023.

The Night Wolves or Night Wolves Motorcycle Club is a Russian motorcycle club that was founded around the Moscow area in 1989. It holds an international status with at least 45 chapters world-wide.

The Russo-Ukrainian War began in February 2014. Following Ukraine's Revolution of Dignity, Russia occupied and annexed Crimea from Ukraine and supported pro-Russian separatists fighting the Ukrainian military in the Donbas War. These first eight years of conflict also included naval incidents and cyberwarfare. In February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine and began occupying more of the country, starting the biggest conflict in Europe since World War II. The war has resulted in a refugee crisis and tens of thousands of deaths.

Media portrayals of the Russo-Ukrainian War, including skirmishes in eastern Donbas and the 2014 Ukrainian revolution after the Euromaidan protests, the subsequent 2014 annexation of Crimea, incursions into Donbas, and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, have differed widely between Ukrainian, Western and Russian media. Russian, Ukrainian, and Western media have all, to various degrees, been accused of propagandizing, and of waging an information war.

The 12th Special Operations Brigade "Azov" is a formation of the National Guard of Ukraine formerly based in Mariupol, in the coastal region of the Sea of Azov, from which it derives its name. It was founded in May 2014 as the Azov Battalion, a self-funded volunteer militia under the command of Andriy Biletsky, to fight Russian-backed forces in the Donbas War. It was formally incorporated into the National Guard on 11 November 2014, and redesignated Special Operations Detachment "Azov", also known as the Azov Regiment. In February 2023, the Ukrainian Ministry of Internal Affairs announced that Azov was to be expanded as a brigade of the new Offensive Guard.

The propaganda of the Russian Federation promotes views, perceptions or agendas of the government. The media include state-run outlets and online technologies, and may involve using "Soviet-style 'active measures' as an element of modern Russian 'political warfare'". Notably, contemporary Russian propaganda promotes the cult of personality of Vladimir Putin and positive views of Soviet history. Russia has established a number of organizations, such as the Presidential Commission of the Russian Federation to Counter Attempts to Falsify History to the Detriment of Russia's Interests, the Russian web brigades, and others that engage in political propaganda to promote the views of the Russian government.

During Ukraine's post-Soviet history, the far-right has remained on the political periphery and been largely excluded from national politics since independence in 1991. Unlike most Eastern European countries which saw far-right groups become permanent fixtures in their countries' politics during the decline and the Dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the national electoral support for far-right parties in Ukraine only rarely exceeded 3% of the popular vote. Far-right parties usually enjoyed just a few wins in single-mandate districts, and no far right candidate for president has ever secured more than 5 percent of the popular vote in an election. Only once in the 1994–2014 period was a radical right-wing party elected to the parliament as an independent organization within the proportional part of the voting: Svoboda in 2012. Since then far-right parties have failed to gain enough votes to attain political representation, even at the height of nationalist sentiment during and after Russia's annexation of Crimea and the Russo-Ukrainian War.

The Russian information war against Ukraine was articulated by the Russian government as part of the Gerasimov doctrine. They believed that Western governments were instigating color revolutions in former Soviet states which posed a threat to Russia.

Ivan Vitalievich Kuliak is a Russian artistic gymnast. He is the 2019 Russian Junior all-around and floor champion and the horizontal bar silver medalist. In March 2022, he gained notoriety for displaying a pro-invasion Z symbol during a medal ceremony, shortly after the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The 2022 FIG World Cup circuit in Artistic Gymnastics is a series of competitions officially organized and promoted by the International Gymnastics Federation (FIG) in 2022. Due to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the International Gymnastics Federation implemented restrictions regarding the use of Russian and Belarusian anthems and flags for the competitions in Cottbus and Doha. Starting March 7, the FIG banned Russian and Belarusian athletes and officials from taking part in FIG-sanctioned competitions.

As part of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Russian state and state-controlled media have spread disinformation in their information war against Ukraine. Ukrainian media and politicians have also been accused of using propaganda and deception, although such efforts have been described as more limited than the Russian disinformation campaign.

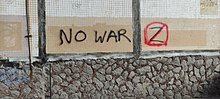

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, anti-war demonstrations and protests broke out across Russia. As well as the demonstrations, a number of petitions and open letters have been penned in opposition to the war, and a number of public figures, both cultural and political, have released statements against the war.

Since early 2022, Russia and Belarus have been boycotted by many companies and organizations in Europe, North America, Australasia, and elsewhere, in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which is supported by Belarus. As of 2 July 2022, the Yale School of Management recorded more than 1,000 companies withdrawing or divesting themselves from Russia, either as a result of sanctions or in protest of Russian actions. Ukrainian National Agency on Corruption Prevention maintains a list called International Sponsors of War that includes companies and individuals still doing business with Russia.

The 2022 Moscow rally, officially known in Russia as "For a world without Nazism", was a political rally and concert at Luzhniki Stadium in Moscow on 18 March 2022, which marked the eighth anniversary of the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation. President Vladimir Putin spoke at the event, justifying the Russian invasion of Ukraine and praising Russian troops to a crowd of 200,000 people, per Moscow City Police. Outlets including the BBC and the Moscow Times reported that state employees were transported to the venue, and other attendees were paid or forced to attend.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine led to widespread international condemnation by political parties and international organisations, as well as by people and groups in the areas of entertainment, media, business, and sport, where boycotts of Russia and Belarus also took place.

Imagery promoting the Soviet Union has been a prominent aspect of the Russo-Ukrainian War, especially since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Both Russia and Russian separatist forces in Ukraine have used Soviet symbols as a means of expressing their antipathy to Ukraine and to Ukrainian decommunization policies. For Russia, in particular, these displays are also part of a broader campaign to de-legitimize Ukrainian statehood and justify annexations of the country's territory, as was the case with Crimea in March 2014 and with southeastern Ukraine in September 2022.

On 24 February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War which began in 2014. The invasion caused Europe's largest refugee crisis since World War II, with more than 8.2 million Ukrainians fleeing the country and a third of the population displaced. The invasion also caused global food shortages. Reactions to the invasion have varied considerably across a broad spectrum of concerns including public reaction, media responses, and peace efforts.