Chemical synapses are biological junctions through which neurons' signals can be sent to each other and to non-neuronal cells such as those in muscles or glands. Chemical synapses allow neurons to form circuits within the central nervous system. They are crucial to the biological computations that underlie perception and thought. They allow the nervous system to connect to and control other systems of the body.

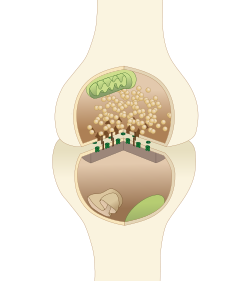

Exocytosis is a form of active transport and bulk transport in which a cell transports molecules out of the cell. As an active transport mechanism, exocytosis requires the use of energy to transport material. Exocytosis and its counterpart, endocytosis, are used by all cells because most chemical substances important to them are large polar molecules that cannot pass through the hydrophobic portion of the cell membrane by passive means. Exocytosis is the process by which a large amount of molecules are released; thus it is a form of bulk transport. Exocytosis occurs via secretory portals at the cell plasma membrane called porosomes. Porosomes are permanent cup-shaped lipoprotein structure at the cell plasma membrane, where secretory vesicles transiently dock and fuse to release intra-vesicular contents from the cell.

An excitatory synapse is a synapse in which an action potential in a presynaptic neuron increases the probability of an action potential occurring in a postsynaptic cell. Neurons form networks through which nerve impulses travel, each neuron often making numerous connections with other cells. These electrical signals may be excitatory or inhibitory, and, if the total of excitatory influences exceeds that of the inhibitory influences, the neuron will generate a new action potential at its axon hillock, thus transmitting the information to yet another cell.

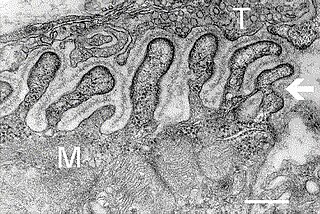

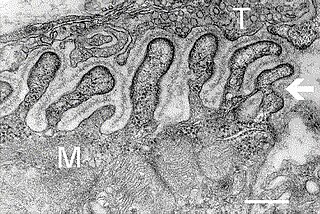

A neuromuscular junction is a chemical synapse between a motor neuron and a muscle fiber.

In a neuron, synaptic vesicles store various neurotransmitters that are released at the synapse. The release is regulated by a voltage-dependent calcium channel. Vesicles are essential for propagating nerve impulses between neurons and are constantly recreated by the cell. The area in the axon that holds groups of vesicles is an axon terminal or "terminal bouton". Up to 130 vesicles can be released per bouton over a ten-minute period of stimulation at 0.2 Hz. In the visual cortex of the human brain, synaptic vesicles have an average diameter of 39.5 nanometers (nm) with a standard deviation of 5.1 nm.

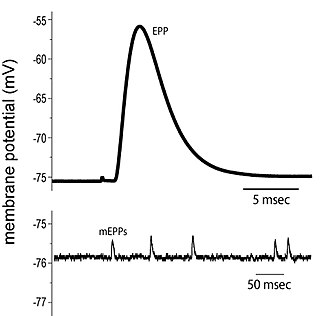

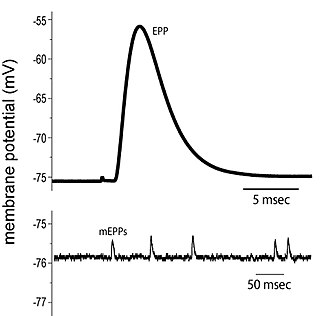

End plate potentials (EPPs) are the voltages which cause depolarization of skeletal muscle fibers caused by neurotransmitters binding to the postsynaptic membrane in the neuromuscular junction. They are called "end plates" because the postsynaptic terminals of muscle fibers have a large, saucer-like appearance. When an action potential reaches the axon terminal of a motor neuron, vesicles carrying neurotransmitters are exocytosed and the contents are released into the neuromuscular junction. These neurotransmitters bind to receptors on the postsynaptic membrane and lead to its depolarization. In the absence of an action potential, acetylcholine vesicles spontaneously leak into the neuromuscular junction and cause very small depolarizations in the postsynaptic membrane. This small response (~0.4mV) is called a miniature end plate potential (MEPP) and is generated by one acetylcholine-containing vesicle. It represents the smallest possible depolarization which can be induced in a muscle.

Molecular neuroscience is a branch of neuroscience that observes concepts in molecular biology applied to the nervous systems of animals. The scope of this subject covers topics such as molecular neuroanatomy, mechanisms of molecular signaling in the nervous system, the effects of genetics and epigenetics on neuronal development, and the molecular basis for neuroplasticity and neurodegenerative diseases. As with molecular biology, molecular neuroscience is a relatively new field that is considerably dynamic.

Neurotransmission is the process by which signaling molecules called neurotransmitters are released by the axon terminal of a neuron, and bind to and react with the receptors on the dendrites of another neuron a short distance away. A similar process occurs in retrograde neurotransmission, where the dendrites of the postsynaptic neuron release retrograde neurotransmitters that signal through receptors that are located on the axon terminal of the presynaptic neuron, mainly at GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses.

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that permits a neuron to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or to the target effector cell.

Synaptic potential refers to the potential difference across the postsynaptic membrane that results from the action of neurotransmitters at a neuronal synapse. In other words, it is the “incoming” signal that a neuron receives. There are two forms of synaptic potential: excitatory and inhibitory. The type of potential produced depends on both the postsynaptic receptor, more specifically the changes in conductance of ion channels in the post synaptic membrane, and the nature of the released neurotransmitter. Excitatory post-synaptic potentials (EPSPs) depolarize the membrane and move the potential closer to the threshold for an action potential to be generated. Inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) hyperpolarize the membrane and move the potential farther away from the threshold, decreasing the likelihood of an action potential occurring. The Excitatory Post Synaptic potential is most likely going to be carried out by the neurotransmitters glutamate and acetylcholine, while the Inhibitory post synaptic potential will most likely be carried out by the neurotransmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glycine. In order to depolarize a neuron enough to cause an action potential, there must be enough EPSPs to both depolarize the postsynaptic membrane from its resting membrane potential to its threshold and counterbalance the concurrent IPSPs that hyperpolarize the membrane. As an example, consider a neuron with a resting membrane potential of -70 mV (millivolts) and a threshold of -50 mV. It will need to be raised 20 mV in order to pass the threshold and fire an action potential. The neuron will account for all the many incoming excitatory and inhibitory signals via summative neural integration, and if the result is an increase of 20 mV or more, an action potential will occur.

Complexin (also known as synaphin) refers to a one of a small set of eukaryotic cytoplasmic neuronal proteins which binds to the SNARE protein complex (SNAREpin) with a high affinity. These are called synaphin 1 and 2. In the presence of Ca2+, the transport vesicle protein synaptotagmin displaces complexin, allowing the SNARE protein complex to bind the transport vesicle to the presynaptic membrane.

The Calyx of Held is a particularly large synapse in the mammalian auditory central nervous system, so named after Hans Held who first described it in his 1893 article Die centrale Gehörleitung because of its resemblance to the calyx of a flower. Globular bushy cells in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus (AVCN) send axons to the contralateral medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (MNTB), where they synapse via these calyces on MNTB principal cells. These principal cells then project to the ipsilateral lateral superior olive (LSO), where they inhibit postsynaptic neurons and provide a basis for interaural level detection (ILD), required for high frequency sound localization. This synapse has been described as the largest in the brain.

Neuromuscular junction disease is a medical condition where the normal conduction through the neuromuscular junction fails to function correctly.

Axon terminals are distal terminations of the telodendria (branches) of an axon. An axon, also called a nerve fiber, is a long, slender projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, that conducts electrical impulses called action potentials away from the neuron's cell body, or soma, in order to transmit those impulses to other neurons, muscle cells or glands.

Cellular neuroscience is a branch of neuroscience concerned with the study of neurons at a cellular level. This includes morphology and physiological properties of single neurons. Several techniques such as intracellular recording, patch-clamp, and voltage-clamp technique, pharmacology, confocal imaging, molecular biology, two photon laser scanning microscopy and Ca2+ imaging have been used to study activity at the cellular level. Cellular neuroscience examines the various types of neurons, the functions of different neurons, the influence of neurons upon each other, and how neurons work together.

The ribbon synapse is a type of neuronal synapse characterized by the presence of an electron-dense structure, the synaptic ribbon, that holds vesicles close to the active zone. It is characterized by a tight vesicle-calcium channel coupling that promotes rapid neurotransmitter release and sustained signal transmission. Ribbon synapses undergo a cycle of exocytosis and endocytosis in response to graded changes of membrane potential. It has been proposed that most ribbon synapses undergo a special type of exocytosis based on coordinated multivesicular release. This interpretation has recently been questioned at the inner hair cell ribbon synapse, where it has been instead proposed that exocytosis is described by uniquantal release shaped by a flickering vesicle fusion pore.

Vesicle fusion is the merging of a vesicle with other vesicles or a part of a cell membrane. In the latter case, it is the end stage of secretion from secretory vesicles, where their contents are expelled from the cell through exocytosis. Vesicles can also fuse with other target cell compartments, such as a lysosome. Exocytosis occurs when secretory vesicles transiently dock and fuse at the base of cup-shaped structures at the cell plasma membrane called porosome, the universal secretory machinery in cells. Vesicle fusion may depend on SNARE proteins in the presence of increased intracellular calcium (Ca2+) concentration.

Thomas Christian Südhof, ForMemRS, is a German-American biochemist known for his study of synaptic transmission. Currently, he is a professor in the School of Medicine in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Physiology, and by courtesy in Neurology, and in Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University.

Synaptic fatigue, or short-term synaptic depression, is an activity-dependent form of short term synaptic plasticity that results in the temporary inability of neurons to fire and therefore transmit an input signal. It is thought to be a form of negative feedback in order to physiologically control particular forms of nervous system activity.

Neurotransmitters are released into a synapse in packaged vesicles called quanta. One quantum generates what is known as a miniature end plate potential (MEPP) which is the smallest amount of stimulation that one neuron can send to another neuron. Quantal release is the mechanism by which most traditional endogenous neurotransmitters are transmitted throughout the body. The aggregate sum of many MEPPs is known as an end plate potential (EPP). A normal end plate potential usually causes the postsynaptic neuron to reach its threshold of excitation and elicit an action potential. Electrical synapses do not use quantal neurotransmitter release and instead use gap junctions between neurons to send current flows between neurons. The goal of any synapse is to produce either an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) or an inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP), which generate or repress the expression, respectively, of an action potential in the postsynaptic neuron. It is estimated that an action potential will trigger the release of approximately 20% of an axon terminal's neurotransmitter load.