The Rings of Power are magical artefacts in J. R. R. Tolkien's legendarium, most prominently in his high fantasy novel The Lord of the Rings. The One Ring first appeared as a plot device, a magic ring in Tolkien's children's fantasy novel, The Hobbit; Tolkien later gave it a backstory and much greater power. He added nineteen other Great Rings, also conferring powers such as invisibility, that it could control, including the Three Rings of the Elves, Seven Rings for the Dwarves, and Nine for Men. He stated that there were in addition many lesser rings with minor powers. A key story element in The Lord of the Rings is the addictive power of the One Ring, made secretly by the Dark Lord Sauron; the Nine Rings enslave their bearers as the Nazgûl (Ringwraiths), Sauron's most deadly servants.

Bilbo's Last Song is a poem by J. R. R. Tolkien, written as a pendant to his fantasy The Lord of the Rings. It was first published in a Dutch translation in 1973, subsequently appearing in English on posters in 1974 and as a picture-book in 1990. It was illustrated by Pauline Baynes, and set to music by Donald Swann and Stephen Oliver. The poem's copyright was owned by Tolkien's secretary, to whom he gave it in gratitude for her work for him.

J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator is a collection of paintings and drawings by J. R. R. Tolkien for his stories, published posthumously in 1995. The book was edited by Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull. It won the 1996 Mythopoeic Scholarship Award for Inklings Studies. The nature and importance of Tolkien's artwork is discussed.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the real-world history and notable fictional elements of J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy universe. It covers materials created by Tolkien; the works on his unpublished manuscripts, by his son Christopher Tolkien; and films, games and other media created by other people.

The works of J. R. R. Tolkien have generated a body of research covering many aspects of his fantasy writings. These encompass The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion, along with his legendarium that remained unpublished until after his death, and his constructed languages, especially the Elvish languages Quenya and Sindarin. Scholars from different disciplines have examined the linguistic and literary origins of Middle-earth, and have explored many aspects of his writings from Christianity to feminism and race.

"Errantry" is a three-page poem by J.R.R. Tolkien, first published in The Oxford Magazine in 1933. It was included in revised and extended form in Tolkien's 1962 collection of short poems, The Adventures of Tom Bombadil. Donald Swann set the poem to music in his 1967 song cycle, The Road Goes Ever On.

Middle-earth is the setting of much of the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy. The term is equivalent to the Miðgarðr of Norse mythology and Middangeard in Old English works, including Beowulf. Middle-earth is the human-inhabited world, that is, the central continent of the Earth, in Tolkien's imagined mythological past. Tolkien's most widely read works, The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, are set entirely in Middle-earth. "Middle-earth" has also become a short-hand term for Tolkien's legendarium, his large body of fantasy writings, and for the entirety of his fictional world.

In the fictional world of J. R. R. Tolkien, Moria, also named Khazad-dûm, is an ancient subterranean complex in Middle-earth, comprising a vast labyrinthine network of tunnels, chambers, mines and halls under the Misty Mountains, with doors on both the western and the eastern sides of the mountain range. Moria is introduced in Tolkien's novel The Hobbit, and is a major scene of action in The Lord of the Rings.

The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien is a selection of the philologist and fantasy author J. R. R. Tolkien's letters. It was published in 1981, edited by Tolkien's biographer Humphrey Carpenter, who was assisted by Christopher Tolkien. The selection, from a large mass of materials, contains 354 letters. These were written between October 1914, when Tolkien was an undergraduate at Oxford, and 29 August 1973, four days before his death. The letters are of interest both for what they show of Tolkien's life and for his interpretations of his Middle-earth writings.

The Silmarillion is a collection of myths and stories in varying styles by the English writer J. R. R. Tolkien. It was edited and published posthumously by his son Christopher Tolkien in 1977, assisted by Guy Gavriel Kay, who became a fantasy author. It tells of Eä, a fictional universe that includes the Blessed Realm of Valinor, the ill-fated region of Beleriand, the island of Númenor, and the continent of Middle-earth, where Tolkien's most popular works—The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings—are set. After the success of The Hobbit, Tolkien's publisher, Stanley Unwin, requested a sequel, and Tolkien offered a draft of the writings that would later become The Silmarillion. Unwin rejected this proposal, calling the draft obscure and "too Celtic", so Tolkien began working on a new story that eventually became The Lord of the Rings.

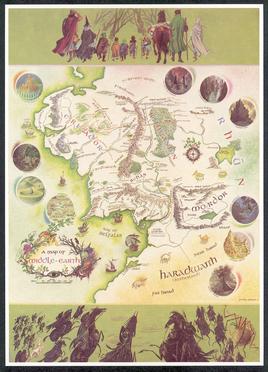

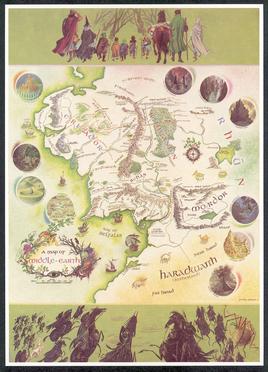

"A Map of Middle-earth" is the name of two colour posters by different artists, Barbara Remington and Pauline Baynes. They depict the north-western region of the fictional continent of Middle-earth. They were published in 1965 and 1970 by the American and British publishers of J. R. R. Tolkien's book The Lord of the Rings. The poster map by Pauline Baynes has been described as "iconic".

Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth is a 2018 art book exploring images of the artwork, illustrations, maps, letters and manuscripts of J. R. R. Tolkien. The book was written by Catherine McIlwaine, Tolkien archivist at the Bodleian Library. It was timed to coincide with an exhibition of the same name, also curated by McIlwaine.

The plants in Middle-earth, the fictional world devised by J. R. R. Tolkien, are a mixture of real plant species with fictional ones. Middle-earth was intended to represent the real world in an imagined past, and in many respects its natural history is realistic.

Trees play multiple roles in J. R. R. Tolkien's fantasy world of Middle-earth, some such as Old Man Willow indeed serving as characters in the plot. Both for Tolkien personally, and in his Middle-earth writings, caring about trees really mattered. Indeed, the Tolkien scholar Matthew Dickerson wrote "It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of trees in the writings of J. R. R. Tolkien."

J. R. R. Tolkien's maps, depicting his fictional Middle-earth and other places in his legendarium, helped him with plot development, guided the reader through his often complex stories, and contributed to the impression of depth and worldbuilding in his writings.

Tolkien's Middle-earth family trees contribute to the impression of depth and realism in the stories set in his fantasy world by showing that each character is rooted in history with a rich network of relationships. J. R. R. Tolkien included multiple family trees in both The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion; they are variously for Elves, Dwarves, Hobbits, and Men.

J. R. R. Tolkien invented heraldic devices for many of the characters and nations of Middle-earth. His descriptions were in simple English rather than in specific blazon. The emblems correspond in nature to their bearers, and their diversity contributes to the richly-detailed realism of his writings.

In Tolkien's legendarium, ancestry provides a guide to character. The apparently genteel Hobbits of the Baggins family turn out to be worthy protagonists of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Bilbo Baggins is seen from his family tree to be both a Baggins and an adventurous Took. Similarly, Frodo Baggins has some relatively outlandish Brandybuck blood. Among the Elves of Middle-earth, as described in The Silmarillion, the highest are the peaceful Vanyar, whose ancestors conformed most closely to the divine will, migrating to Aman and seeing the light of the Two Trees of Valinor; the lowest are the mutable Teleri; and in between are the conflicted Noldor. Scholars have analysed the impact of ancestry on Elves such as the creative but headstrong Fëanor, who makes the Silmarils. Among Men, Aragorn, hero of The Lord of the Rings, is shown by his descent from Kings, Elves, and an immortal Maia to be of royal blood, destined to be the true King who will restore his people. Scholars have commented that in this way, Tolkien was presenting a view of character from Norse mythology, and an Anglo-Saxon view of kingship, though others have called his implied views racist.

J. R. R. Tolkien included many elements in his Middle-earth writings, especially The Lord of the Rings, other than narrative text. These include artwork, calligraphy, chronologies, family trees, heraldry, languages, maps, poetry, proverbs, scripts, glossaries, prologues, and annotations. Scholars have stated that the use of these elements places Tolkien in the tradition of English antiquarianism.

Since the publication of J. R. R. Tolkien's The Hobbit in 1937, artists including Tolkien himself have sought to capture aspects of Middle-earth fantasy novels in paintings and drawings. He was followed in his lifetime by artists whose work he liked, such as Pauline Baynes, Mary Fairburn, Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, and Ted Nasmith, and by some whose work he rejected, such as Horus Engels for the German edition of The Hobbit. Tolkien had strong views on illustration of fantasy, especially in the case of his own works. His recorded opinions range from his rejection of the use of images in his 1936 essay On Fairy-Stories, to agreeing the case for decorative images for certain purposes, and his actual creation of images to accompany the text in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Commentators including Ruth Lacon and Pieter Collier have described his views on illustration as contradictory, and his requirements as being as fastidious as his editing of his novels.