Related Research Articles

Robin Hood is a legendary heroic outlaw originally depicted in English folklore and subsequently featured in literature, theatre, and cinema. He stole from the rich and gave to the poor. According to legend, he was a highly skilled archer and swordsman. In some versions of the legend, he is depicted as being of noble birth, and in modern retellings he is sometimes depicted as having fought in the Crusades before returning to England to find his lands taken by the Sheriff. In the oldest known versions, he is instead a member of the yeoman class. He is traditionally depicted dressed in Lincoln green.

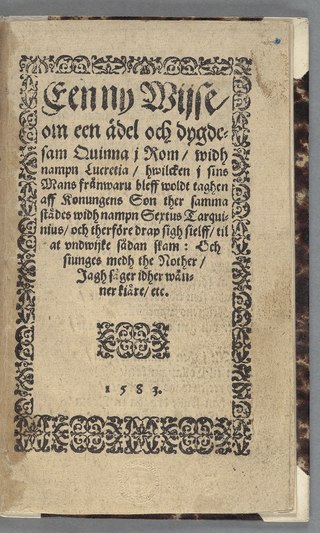

A broadside is a single sheet of inexpensive paper printed on one side, often with a ballad, rhyme, news and sometimes with woodcut illustrations. They were one of the most common forms of printed material between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, particularly in Britain, Ireland and North America because they are easy to produce and are often associated with one of the most important forms of traditional music from these countries, the ballad.

Robin Hood's Chase is an English folk song about Robin Hood, and a sequel to "Robin Hood and Queen Katherine". This song has survived as, among other forms, a late seventeenth-century English broadside ballad. It is one of several ballads about the medieval folk hero that form part of the Child Ballads.

Robin Hood's Death, also known as Robin Hoode his Death, is an Early Modern English ballad of Robin Hood. It dates from at the latest the 17th century, and possibly originating earlier, making it one of the oldest existing tales of Robin Hood. It is a longer version of the last six stanzas of A Gest of Robyn Hode, suggesting that one of the authors was familiar with the other work and made an expansion or summary of the other, or else both were drawing from a lost common tale. The surviving version in the Percy Folio is fragmentary, with sections missing. A more complete but later version is from the middle of the 18th century, and is written in modern English. Both versions were later published by Francis James Child as Child ballad #120 in his influential collection of popular ballads.

Robin Hood and the Tanner is a late seventeenth-century English broadside ballad and folk song that forms part of the Robin Hood canon.

Robin Hood and the Potter is a 15th century ballad of Robin Hood. While usually classed with other Robin Hood ballads, it does not appear to have originally been intended to be sung, but rather recited by a minstrel, and thus is closer to a poem. It is one of the very oldest pieces of the surviving Robin Hood legend, with perhaps only Robin Hood and the Monk older than it. It inspired a short play intended for use in May Day games, attested to around 1560. It was later published by Francis James Child as Child ballad #121 in his influential collection of popular ballads in the 1880s.

Robin Hood and the Butcher is a story in the Robin Hood canon which has survived as, among other forms, a late seventeenth-century English broadside ballad, and is one of several ballads about the medieval folk hero that form part of the Child ballad collection, which is one of the most comprehensive collections of traditional English ballads. It may have been derived from the similar Robin Hood and the Potter.

Robin Hood's Golden Prize is an English folk song. It is a story in the Robin Hood canon, which has survived as, among other forms, a late seventeenth-century English broadside ballad, and is one of several ballads about the medieval folk hero that form part of the Child ballad collection.

Robin Hood's Delight is an English folk song. It is a story in the Robin Hood canon which has survived as, among other forms, a late seventeenth-century English broadside ballad, and is one of several ballads about the medieval folk hero that form part of the Child ballad collection, which is one of the most comprehensive collections of traditional English ballads.

A Gest of Robyn Hode is one of the earliest surviving texts of the Robin Hood tales. Written in late Middle English poetic verse, it is an early example of an English language ballad, in which the verses are grouped in quatrains with an ABCB rhyme scheme, also known as ballad stanzas. Gest, which means tale or adventure, is a compilation of various Robin Hood tales, arranged as a sequence of adventures involving the yeoman outlaws Robin Hood and Little John, the poor knight Sir Richard at the Lee, the greedy abbot of St Mary's Abbey, the villainous Sheriff of Nottingham, and King Edward of England. The work survives in printed editions from the early 16th century, just some 30 years after the first printing press was brought to England. Its popularity is proven by the fact that portions of more than ten 16th- and 17th-century printed editions have been preserved. While the oldest surviving copies are from the early 16th century, many scholars believe that based on the style of writing, the work likely dates to the 15th century, perhaps even as early as 1400. The story itself is set somewhere from 1272 to 1483, during the reign of a King Edward; this contrasts with later works, which generally placed Robin Hood earlier in 1189–1216, during the reigns of Richard I of England and John, King of England.

Robin Hood and the Bishop is an English-language folk song describing an adventure of Robin Hood. This song has also survived as a late seventeenth-century English broadside ballad, and is one of several ballads about the medieval folk hero that form part of the Child ballad collection, which is one of the most comprehensive collections of traditional English ballads.

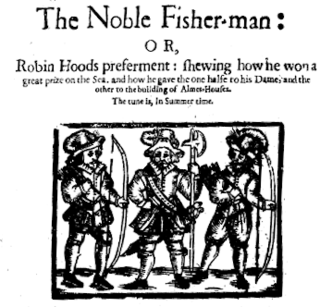

The Noble Fisherman, also known as Robin Hood's Preferment and Robin Hood's Fishing, is a 17th-century ballad of Robin Hood. Unusually, it depicts Robin Hood as a hero of the sea, rather than his usual portrayal as someone who operated in the greenwood forest. It seems to have been quite popular for the first two centuries of its existence, although it eventually lost prominence and was less used in adaptations of Robin Hood from the 19th and 20th centuries. It was later published by Francis James Child in the 1880s as Child Ballad #148 in his influential collection of popular ballads.

Robin Hood and the Monk is a Middle English ballad and one of the oldest surviving ballads of Robin Hood. The earliest surviving document with the work is from around 1450, and it may have been composed even earlier in the 15th century. It is also one of the longest ballads at around 2,700 words. It is considered one of the best of the original ballads of Robin Hood.

Robyn and Gandeleyn is an English ballad. The poem is in Sloane Manuscript 2593, a document of lyrics and carols which dates from around 1450. It was first printed by Joseph Ritson in his 1790 collection Ancient Songs. It was later republished in the second half of the 19th century in an anthology of traditional English and Scottish ballads by Francis James Child known as the Child Ballads, where it is Child Ballad 115. Child also divided the continuous text into seventeen stanzas.

Robin Hood and the Shepherd is a story in the Robin Hood canon which has survived as, among other forms, a late seventeenth-century English broadside ballad, and is one (#135) out of several ballads about the medieval folk hero that form part of the Child ballad collection, which is one of the most comprehensive collections of traditional English ballads.

"Robin Hood and the Beggar" is a story in the Robin Hood canon which has survived as, among other forms, a late seventeenth-century English broadside ballad, and is a pair out of several ballads about the medieval folk hero that form part of the Child ballad collection, which is one of the most comprehensive collections of traditional English ballads. These two ballads share the same basic plot device in which the English folk hero Robin Hood meets a beggar.

An itinerant poet or strolling minstrel was a wandering minstrel, bard, musician, or other poet common in medieval Europe but extinct today. Itinerant poets were from a lower class than jesters or jongleurs, as they did not have steady work, instead travelling to make a living.

Robin Hood and Little John is Child ballad 125. It is a story in the Robin Hood canon which has survived as, among other forms, a late seventeenth-century English broadside ballad, and is one of several ballads about the medieval folk hero that form part of the Child ballad collection, which is one of the most comprehensive collections of traditional English ballads.

The English Broadside Ballad Archive (EBBA) is a digital library of 17th-century English Broadside Ballads, a project of the English Department of the University of California, Santa Barbara. The project archives ballads in multiple accessible digital formats.

References

- ↑ Archived October 9, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ This synopsis refers to a text transcription of a 17th-century broadside ballad version of the tale held in the Roxburghe collection of the British Library.

- ↑ Watt (1993) , pp. 39–40

- ↑ Watt (1993) , pp. 39–40, quoting Edward Dering, A brief and necessary instruction (1572), sig.A2v.

- ↑ Child (2003) , p. 42

- ↑ Brown (2010) , p. 67; Brown's italics

- 1 2 Brown (2010) , p. 69

- 1 2 Fumerton & Guerrini (2010) , p. 1

- ↑ Holt (1989) , pp. 37–38

- ↑ Holt (1989) , p. 10

- ↑ Singman (1998) , p. 46, and first chapter as a whole

- ↑ "Archived copy". ebba.english.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Bibliography

- Brown, Mary Ellen (2010). "Child's ballads and the broadside conundrum". In Patricia Fumerton; Anita Guerrini; Kris McAbee (eds.). Ballads and Broadsides in Britain, 1500–1800. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company. pp. 57–72. ISBN 978-0-7546-6248-8.

- Child, Francis James, ed. (2003) [1888–1889]. The English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Vol. 3. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

- Fumerton, Patricia; Guerrini, Anita (2010). "Introduction: straws in the wind". In Patricia Fumerton; Anita Guerrini; Kris McAbee (eds.). Ballads and Broadsides in Britain, 1500–1800. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company. pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-0-7546-6248-8.

- Holt, J. C. (1989). Robin Hood. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27541-6.

- Singman, Jeffrey L. (1998). Robin Hood: The Shaping of the Legend. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-30101-8.

- Watt, Tessa (1993). Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550–1640. Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521458276.