Racism is discrimination and prejudice against people based on their race or ethnicity. Racism can be present in social actions, practices, or political systems that support the expression of prejudice or aversion in discriminatory practices. The ideology underlying racist practices often assumes that humans can be subdivided into distinct groups that are different in their social behavior and innate capacities and that can be ranked as inferior or superior. Racist ideology can become manifest in many aspects of social life. Associated social actions may include nativism, xenophobia, otherness, segregation, hierarchical ranking, supremacism, and related social phenomena.

The Aryan race is an obsolete historical race concept that emerged in the late-19th century to describe people who descend from the Proto-Indo-Europeans as a racial grouping. The terminology derives from the historical usage of Aryan, used by modern Indo-Iranians as an epithet of "noble". Anthropological, historical, and archaeological evidence does not support the validity of this concept.

The racial policy of Nazi Germany was a set of policies and laws implemented in Nazi Germany under the dictatorship of Adolf Hitler, based on pseudoscientific and racist doctrines asserting the superiority of the putative "Aryan race", which claimed scientific legitimacy. This was combined with a eugenics program that aimed for "racial hygiene" by compulsory sterilization and extermination of those who they saw as Untermenschen ("sub-humans"), which culminated in the Holocaust.

The Völkisch movement was a German ethno-nationalist movement active from the late 19th century through to the Nazi era, with remnants in the Federal Republic of Germany afterwards. Erected on the idea of "blood and soil", inspired by the one-body-metaphor, and by the idea of naturally grown communities in unity, it was characterized by organicism, racialism, populism, agrarianism, romantic nationalism and – as a consequence of a growing exclusive and ethnic connotation – by antisemitism from the 1900s onward. Völkisch nationalists generally considered the Jews to be an "alien people" who belonged to a different Volk from the Germans.

The term racial hygiene was used to describe an approach to eugenics in the early 20th century, which found its most extensive implementation in Nazi Germany. It was marked by efforts to avoid miscegenation, analogous to an animal breeder seeking purebred animals. This was often motivated by the belief in the existence of a racial hierarchy and the related fear that "lower races" would "contaminate" a "higher" one. As with most eugenicists at the time, racial hygienists believed that the lack of eugenics would lead to rapid social degeneration, the decline of civilization by the spread of inferior characteristics.

Organicism is the philosophical position that states that the universe and its various parts ought to be considered alive and naturally ordered, much like a living organism. Vital to the position is the idea that organicistic elements are not dormant "things" per se but rather dynamic components in a comprehensive system that is, as a whole, everchanging. Organicism is related to but remains distinct from holism insofar as it prefigures holism; while the latter concept is applied more broadly to universal part-whole interconnections such as in anthropology and sociology, the former is traditionally applied only in philosophy and biology. Furthermore, organicism is incongruous with reductionism because of organicism's consideration of "both bottom-up and top-down causation." Regarded as a fundamental tenet in natural philosophy, organicism has remained a vital current in modern thought, alongside both reductionism and mechanism, that has guided scientific inquiry since the early 17th century.

Biopolitics refers to the political relations between the administration of life and a locality's populations, where politics and law evaluate life based on perceived constants and traits. French philosopher Michel Foucault, who wrote about and gave lectures dedicated to his theory of biopolitics, wrote that it is "to ensure, sustain, and multiply life, to put this life in order."

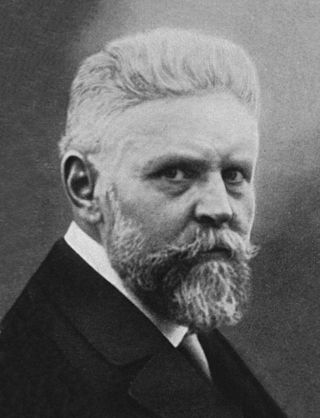

Alfred Ploetz was a German physician, biologist, Social Darwinist, and eugenicist known for coining the term racial hygiene (Rassenhygiene), a form of eugenics, and for promoting the concept in Germany.

Detlev Julio K. Peukert was a German historian, noted for his studies of the relationship between what he called the "spirit of science" and the Holocaust and in social history and the Weimar Republic. Peukert taught modern history at the University of Essen and served as director of the Research Institute for the History of the Nazi Period. Peukert was a member of the German Communist Party until 1978, when he joined the Social Democratic Party of Germany. A politically engaged historian, Peukert was known for his unconventional take on modern German history, and in an obituary, the British historian Richard Bessel wrote that it was a major loss that Peukert had died at the age of 39 as a result of AIDS.

Fritz Gottlieb Karl Lenz was a German geneticist, member of the Nazi Party, and influential specialist in eugenics in Nazi Germany.

The Nazi Party of Germany adopted and developed several pseudoscientific racial classifications as part of its ideology (Nazism) in order to justify the genocide of groups of people which it deemed racially inferior. The Nazis considered the putative "Aryan race" a superior "master race", and they considered black people, mixed-race people, Slavs, Roma, Jews and other ethnicities racially inferior "sub-humans", whose members were only suitable for slave labor and extermination. These beliefs stemmed from a mixture of 19th-century anthropology, scientific racism, and anti-Semitism. The term "Aryan" belongs in general to the discourses of Volk.

Nazi eugenics refers to the social policies of eugenics in Nazi Germany, composed of various ideas about genetics. The racial ideology of Nazism placed the biological improvement of the German people by selective breeding of "Nordic" or "Aryan" traits at its center. These policies were used to justify the involuntary sterilization and mass-murder of those deemed "undesirable".

An Investigation of Global Policy with the Yamato Race as Nucleus was a secret Japanese government report created by the Ministry of Health and Welfare's Institute of Population Problems, and completed on July 1, 1943.

Volkstum is the entirety of utterances of a Volk or of an ethnic minority over its lifetime, expressing a "Volkscharakter" which the people of such an ethnicity allegedly have in common. It was the defining idea of the Völkisch movement.

The Expert Committee on Questions of Population and Racial Policy was a Nazi Germany committee formed on 2 June 1933 that planned Nazi racial policy. On July 14, 1933, the committee's recommendations were made law as the Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring, or the "Sterilization Law".

Nazism, the common name in English for National Socialism, is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Nazi Germany. During Hitler's rise to power in 1930s Europe, it was frequently referred to as Hitlerism. The later related term "neo-Nazism" is applied to other far-right groups with similar ideas which formed after the Second World War. Nazism is a form of fascism, with disdain for liberal democracy and the parliamentary system. It incorporates a dictatorship, fervent antisemitism, anti-communism, anti-Slavism, scientific racism, white supremacy, Nordicism, social Darwinism and the use of eugenics into its creed. Its extreme nationalism originated in pan-Germanism and the ethno-nationalist Völkisch movement which had been a prominent aspect of German ultranationalism since the late 19th century. Nazism was strongly influenced by the Freikorps paramilitary groups that emerged after Germany's defeat in World War I, from which came the party's underlying "cult of violence". It subscribed to pseudo-scientific theories of a racial hierarchy, identifying ethnic Germans as part of what the Nazis regarded as an Aryan or Nordic master race. Nazism sought to overcome social divisions and create a homogeneous German society based on racial purity which represented a people's community. The Nazis aimed to unite all Germans living in historically German territory, as well as gain additional lands for German expansion under the doctrine of Lebensraum and exclude those whom they deemed either Community Aliens or "inferior" races.

The body politic is a polity—such as a city, realm, or state—considered metaphorically as a physical body. Historically, the sovereign is typically portrayed as the body's head, and the analogy may also be extended to other anatomical parts, as in political readings of Aesop's fable of "The Belly and the Members". The image originates in ancient Greek philosophy, beginning in the 6th century BC, and was later extended in Roman philosophy. Following the high and late medieval revival of the Byzantine Corpus Juris Civilis in Latin Europe, the "body politic" took on a jurisprudential significance by being identified with the legal theory of the corporation, gaining salience in political thought from the 13th century on. In English law the image of the body politic developed into the theory of the king's two bodies and the Crown as corporation sole.

Geza von Hoffmann (1885–1921) was a prominent Austrian-Hungarian eugenicist and writer. He lived for a time in California as the Austrian Vice-Consulate where he observed and wrote on eugenics practices in the United States.

Ethnic nationalism, also known as ethnonationalism, is a form of nationalism wherein the nation and nationality are defined in terms of ethnicity, with emphasis on an ethnocentric approach to various political issues related to national affirmation of a particular ethnic group.

Friedrich Wilhelm Schallmayer was Germany's first advocate of eugenics who, along with Alfred Ploetz, founded the German eugenics movement. Schallmayer made a lasting impact on the eugenics movement.