Plant, microbe and insect chemical ecology

Plant, microbe, and insect chemical ecology focuses on the role of chemical cues and signals in mediating interactions with their abiotic (e.g. ability of some bacterium to reduce metals in the surrounding environment) and biotic environment (e.g. microorganisms, phytophagous insects, and pollinators). [10] [11] Cues allow for organisms to monitor interactions with the environment and to adjust accordingly through changes in chemical abundance as a response. [12] Changes in compound abundance allows for defensive measures to be enacted, e.g. attracts for predators. [12]

Plant-insect interactions

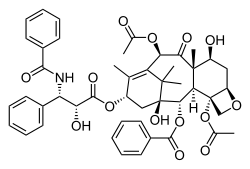

The chemical ecology of plant-insect interaction is a significant subfield of chemical ecology. [2] [13] [14] In particular, plants and insects are often involved in a chemical evolutionary arms race. [15] As plants develop chemical defenses to herbivory, insects which feed on them co-evolved to develop immunity to these poisons, and in some cases, repurpose these poisons for their own chemical defense against predators. [15] For example, caterpillars of the monarch butterfly sequester cardenolide toxins from their milkweed host-plants and are able to use them as an anti-predator defense. [15] Whereas most insects are killed by cardenolides, which are potent inhibitors of the Na+/K+-ATPase, monarchs have evolved resistance to the toxin over their long evolutionary history with milkweeds. Other examples of sequestration include the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta , which use nicotine sequestered from tobacco plants in predator defense; [13] and the bella moth, which secretes a quinone-containing froth to deter predators obtained from feeding on Crotalaria plants as a caterpillar.

Chemical ecologists also study chemical interactions involved in indirect defenses of plants, such as the attraction of predators and parasitoids through herbivore-induced volatile organic compounds (VOCs). [12]

Plant-microbe interactions

Plant interactions with microorganisms are also mediated by chemistry. Both constitutive and induced secondary metabolites (specialized metabolites in modern terminology) are involved in plant defense against pathogens and chemical signals are also important in the establishment and maintenance of resource mutualisms. For example, both rhizobia and mycorrhizae depend on chemical signals, such as strigolactones and flavanoids exuded from plant roots, in order to find a suitable host.

For microbes to gain access to the plant, they must be able to penetrate the layer of wax that forms a hydrophobic barrier on the plant's surface. [16] Many plant-pathogenic microbes secrete enzymes that break down these cuticular waxes. [17] Mutualistic microbes on the other hand may be granted access. For example, rhizobia secrete Nod factors that trigger the formation of an infection thread in receptive plants. The rhizobial symbionts can then travel through this infection thread to gain entrance to root cells.

Mycorrhizae and other fungal endophytes may also benefit their host plants by producing antibiotics or other secondary metabolites that ward off harmful fungi, bacteria and herbivores in the soil. [18] Some entomopathogenic fungi can also form endophytic relationships with plants and may even transfer nitrogen directly to plants from insects they consume in the surrounding soil. [19]

Plant-plant interactions

Allelopathy

Allelopathy is a sub-field of chemical ecology which focuses on secondary (known as allelochemicals) produced by plants or microorganisms that can inhibit the growth and formation of neighboring plants or microorganisms within the natural community. [20] [21] Many examples of allelopathic competition have been controversial due to the difficulty of positively demonstrating a causal link between allelopathic substances and plant performance under natural conditions, [22] but it is widely accepted that phytochemicals are involved in competitive interactions between plants. One of the clearest examples of allelopathy is the production of juglone by walnut trees, whose strong competitive effects on neighboring plants were recognized in the ancient world as early as 36 BC. [23] Allelopathic compounds have also become an interest in agriculture as an alternative to weed management over synthetic herbicides, e.g. wheat production. [24]

Plant-plant communication

Plants communicate with each other through both airborne and below-ground chemical cues. For example, when damaged by an herbivore, many plants emit an altered bouquet of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Various C6 fatty acids and alcohols (sometimes known as green leaf volatiles) are often emitted from damaged leaves, since they are break-down products of plant cell membranes. These compounds (familiar to many as the smell of freshly mown grass) can be perceived by neighboring plants where they may trigger the induction of plant defenses. [25] It is debated to what extent this communication reflects a history of active selection due to mutual benefit as opposed to "eavesdropping" on cues unintentionally emitted by neighboring plants. [26]

Insect-reptile interactions

Further information: predator-prey arms race

Reptiles interaction also contribute to chemical ecology via bioaccumulation or neutralization of toxic compounds. Diablito poison frog (Oophaga sylvatica) which feeds on leaf litter arthropods sequesters the poison cardenolides with no self harm. [27] [28] Species of dart frogs have evolved in similar fashion to the insects they consume via modification to their Na+/K+-ATPase. [28] Again, similar to the insects they prey upon, the dart frog physiology has changed to allow for secretion of toxic chemicals such as batrachotoxins found on the skin of certain neotropical dendrobatid frogs. [29] Modification to the Na+/K+-ATPase illustrates a co-evolution based on a predator-prey arms race where each must keep evolving to survive. [15] [28] Another example is the interactions between the horned lizards (Phrynosoma spp.) and harvester ants (Pogonomyrmex spp.). [30] Horned lizards evolution has shown the blood contains a factor that metabolizes toxins produced by harvester ants. The metabolized poison is broken down and used in a specialized blood squirting defensive mechanism to defend the horned lizard against predators. [31]

Insect-mammal interactions

Mammals such as lemurs and monkeys demonstrate application of chemicals similar to how humans use chemicals for pest management and medical use. [32] [33] [34] These applications vary from prevention of internal and external parasites or pathogens, decrease likelihood of infection, increase reproductive function, reducing inflammation, social cues, and more. [32] [34] Red-fronted lemurs (Eulemur ruffrons) have evolved two pathways, preventive measure for avoiding bioaccumulation, allowing for the modification of 2-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone and 2-methoxy-3-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone a secretion of Spirostreptidae millipedes shown to inhibit certain bacterial species. [33] Red-fronted lemurs have also been observed in rubbing the secretion on their fur similar to capuchins, this action uses benzoquinone compounds as repellent for various insects such as ticks and mosquitoes. [34] [35] [36]