The Sand Creek massacre was a massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho people by the U.S. Army in the American Indian Wars that occurred on November 29, 1864, when a 675-man force of the Third Colorado Cavalry under the command of U.S. Volunteers Colonel John Chivington attacked and destroyed a village of Cheyenne and Arapaho people in southeastern Colorado Territory, killing and mutilating an estimated 70 to over 600 Native American people. Chivington claimed 500 to 600 warriors were killed. However, most sources estimate around 150 people were killed, about two-thirds of whom were women and children. The location has been designated the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site and is administered by the National Park Service. The massacre is considered part of a series of events known as the Colorado Wars.

John Milton Chivington was a Methodist pastor and Mason who served as a colonel in the United States Volunteers during the New Mexico Campaign of the American Civil War. He led a rear action against a Confederate supply train in the Battle of Glorieta Pass that had the effect of ending the Confederacy's campaigns in the Western states, and was then appointed a colonel of cavalry during the Colorado War.

Black Kettle was a leader of the Southern Cheyenne during the American Indian Wars. Born to the Northern Só'taeo'o / Só'taétaneo'o band of the Northern Cheyenne in the Black Hills of present-day South Dakota, he later married into the Wotápio / Wutapai band of the Southern Cheyenne.

The Colorado Department of Corrections is the principal department of the Colorado state government that operates the state prisons. It has its headquarters in the Springs Office Park in unincorporated El Paso County, Colorado, near Colorado Springs. The Colorado Department of Corrections runs 20 state-run prisons and also has been affiliated with 7 for-profit prisons in Colorado, of which the state currently contracts with 3 for-profit prisons.

The Territory of Colorado was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from February 28, 1861, until August 1, 1876, when it was admitted to the Union as the 38th State of Colorado.

John Evans was an American politician, physician, founder of various hospitals and medical associations, railroad promoter, second governor of the Territory of Colorado, and namesake of Evanston, Illinois; Evans, Colorado; and formerly Mount Evans, Colorado.

The Colorado War was an Indian War fought in 1864 and 1865 between the Southern Cheyenne, Arapaho, and allied Brulé and Oglala Lakota peoples versus the U.S. Army, Colorado militia, and white settlers in Colorado Territory and adjacent regions. The Kiowa and the Comanche played a minor role in actions that occurred in the southern part of the Territory along the Arkansas River. The Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Lakota Sioux played the major role in actions that occurred north of the Arkansas River and along the South Platte River, the Great Platte River Road, and the eastern portion of the Overland Trail. The United States government and Colorado Territory authorities participated through the 1st Colorado Cavalry Regiment, often called the Colorado volunteers. The war was centered on the Colorado Eastern Plains, extending eastward into Kansas and Nebraska.

The 3rd Colorado Cavalry Regiment was a Union Army unit formed in the mid-1860s when increased traffic on the United States emigrant trails and settler encroachment resulted in numerous attacks against them by the Cheyenne and Arapaho. The Hungate massacre and the display in Denver of mutilated victims raised political pressure for the government to protect its people. Governor John Evans sought and gained authorization from the War Department in Washington to found the Third. More a militia than a military unit, the "Bloodless Third" was composed of "100-daysers," that is, volunteers who signed on for 100 days to fight against the Indians. The unit's only commander was Col. George L. Shoup, a politician from Colorado. The regiment was assigned to the District of Colorado commanded by Col. John M. Chivington.

William Wells Bent was a frontier trader and rancher in the American West, with forts in Colorado. He also acted as a mediator among the Cheyenne Nation, other Native American tribes and the expanding United States. With his brothers, Bent established a trade business along the Santa Fe Trail. In the early 1830s Bent built an adobe fort, called Bent's Fort, along the Arkansas River in present-day Colorado. Furs, horses and other goods were traded for food and other household goods by travelers along the Santa Fe trail, fur-trappers, and local Mexican and Native American people. Bent negotiated a peace among the many Plains tribes north and south of the Arkansas River, as well as between the Native American and the United States government.

Samuel Forster Tappan was an American journalist, military officer, abolitionist and a Native American rights activist. Appointed as a member of the Indian Peace Commission in 1867 to reach peace with the Plains Indians, he advocated self-determination for native tribes. He proposed the federal government replace military jurisdiction over tribal matters with a form of civil law on reservations, applied by the tribes themselves.

The Treaty of Fort Wise of 1861 was a treaty entered into between the United States and six chiefs of the Southern Cheyenne and four of the Southern Arapaho Indian tribes. A significant proportion of Cheyennes opposed this treaty on the grounds that only a minority of Cheyenne chiefs had signed, and without the consent or approval of the rest of the tribe. Different responses to the treaty became a source of conflict between whites and Indians, leading to the Colorado War of 1864, including the Sand Creek Massacre.

Edward Wanshear Wynkoop was a US Army officer during the American Civil War and later an Indian agent. He was a founder of the city of Denver, Colorado. Wynkoop Street in Denver is named after him.

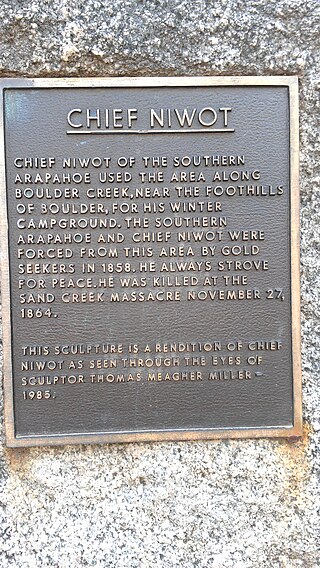

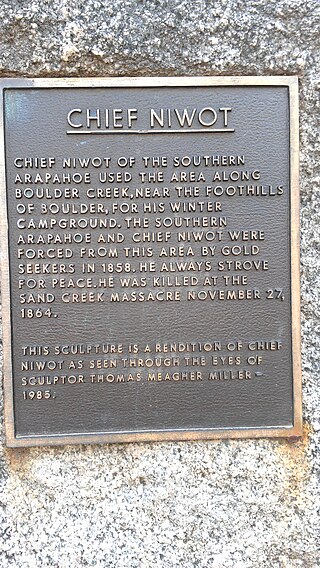

Chief Niwot or Left Hand(-ed) was a Southern Arapaho chief, diplomat, and interpreter who negotiated for peace between white settlers and the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes during the Pike's Peak Gold Rush and Colorado War.

George Bent, also named Ho—my-ike in Cheyenne, was a Cheyenne-Anglo who became a Confederate soldier during the American Civil War and waged war against Americans as a Cheyenne warrior afterward. He was the mixed-race son of Owl Woman, daughter of White Thunder, a Cheyenne chief and keeper of the Medicine Arrows, and the American William Bent, founder of the trading post named Bent's Fort and a trading partnership with his brothers and Ceran St. Vrain. Bent was born near present-day La Junta, Colorado, and was reared among both his mother's people, his father and other European Americans at the fort, and other whites from the age of 10 while attending boarding school in St. Louis, Missouri. He identified as Cheyenne.

Bent's New Fort was a historic fort and trading post along the banks of the Arkansas River in what is now Bent County, Colorado, about nine miles west of Lamar, on the Mountain Route branch of the Santa Fe Trail. William Bent operated a trading post with limited success at the site and in 1860 leased the fort to the United States government, which operated it as a military outpost until 1867. In 1862, it was named Fort Lyon. The fort was abandoned after a flood of the Arkansas River in 1867.

Fort Weld, also called Camp Weld, began as a military camp on 30 acres east of the Platte River in what is now the La Alma-Lincoln Park neighborhood of Denver, Colorado. It was named for Lewis Ledyard Weld, the first Territorial Secretary. The central square of the post was used to practice drills of the troops. Buildings—soldier's quarters, officers' headquarters, mess rooms, a hospital, and a guard house—surrounded the square. The main entrance to the camp was on the eastern side of the post. It was established in September 1861 and abandoned in 1865.

Amache Ochinee Prowers, also known as Walking Woman, was a Native American activist, advocate, cattle rancher, and operator of a store on the Santa Fe Trail. Her father was a Cheyenne peace chief who was killed during the Sand Creek massacre on November 29, 1864, after which she became a mediator between Colorado territorial settlers, Mexicans, and Native Americans during the 1860s and 1870s. She was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame in 2018.

John Wesley Prowers was an American trader, cattle rancher, legislator, and businessman in the territory and state of Colorado. Married to Amache Prowers, a Cheyenne woman, his father-in-law was a Cheyenne chief who negotiated for peace and was killed during the Sand Creek massacre.

Ochinee, also known as Lone Bear and One-Eye, was a Native American Peace Chief of the Cheyenne tribe. He was the father of Amache Prowers, a tradeswoman, advocate and leader among the Southern Cheyenne. Ochinee, who had worked to create peace for the Cheyenne, died during the Sand Creek massacre on November 29, 1864.

White Antelope was a chief of the Southern Cheyenne. He was known for his advocacy of peace between white Americans living in the Great Plains until his killing at the Sand Creek massacre. Accounts of the massacre conflict as to whether White Antelope led his people in resistance to the attack or continued to advocate for peace until his death. White Antelope's body was desecrated after the massacre, and the blanket he was wearing stolen.