Related Research Articles

Formica exsecta is a species of ant found from Western Europe to Asia.

An ant colony is a population of ants, typically from a single species, capable of maintaining their complete lifecycle. Ant colonies are eusocial, communal, and efficiently organized and are very much like those found in other social Hymenoptera, though the various groups of these developed sociality independently through convergent evolution. The typical colony consists of one or more egg-laying queens, numerous sterile females and, seasonally, many winged sexual males and females. In order to establish new colonies, ants undertake flights that occur at species-characteristic times of the day. Swarms of the winged sexuals depart the nest in search of other nests. The males die shortly thereafter, along with most of the females. A small percentage of the females survive to initiate new nests.

The pharaoh ant is a small (2 mm) yellow or light brown, almost transparent ant notorious for being a major indoor nuisance pest, especially in hospitals. A cryptogenic species, it has now been introduced to virtually every area of the world, including Europe, the Americas, Australasia and Southeast Asia. It is a major pest in the United States, Australia, and Europe. The ant's common name is possibly derived from the mistaken belief that it was one of the Egyptian (pharaonic) plagues.

The name army ant (or legionary ant or marabunta) is applied to over 200 ant species in different lineages. Because of their aggressive predatory foraging groups, known as "raids", a huge number of ants forage simultaneously over a limited area.

Atta sexdens is a species of leafcutter ant belonging to the tribe Attini, native to America, from the southern United States (Texas) to northern Argentina. They are absent from Chile. They cut leaves to provide a substrate for the fungus farms which are their principal source of food. Their societies are among the most complex found in social insects. A. sexdens is an ecologically important species, but also an agricultural pest. Other Atta species, such as Atta texana, Atta cephalotes and others, have similar behavior and ecology.

Bombus terrestris, the buff-tailed bumblebee or large earth bumblebee, is one of the most numerous bumblebee species in Europe. It is one of the main species used in greenhouse pollination, and so can be found in many countries and areas where it is not native, such as Tasmania. Moreover, it is a eusocial insect with an overlap of generations, a division of labour, and cooperative brood care. The queen is monogamous which means she mates with only one male. B. terrestris workers learn flower colours and forage efficiently.

Haplodiploidy is a sex-determination system in which males develop from unfertilized eggs and are haploid, and females develop from fertilized eggs and are diploid. Haplodiploidy is sometimes called arrhenotoky.

Bombus ternarius, commonly known as the orange-belted bumblebee or tricolored bumblebee, is a yellow, orange and black bumblebee. It is a ground-nesting social insect whose colony cycle lasts only one season, common throughout the northeastern United States and much of Canada. The orange-belted bumblebee forages on Rubus, goldenrods, Vaccinium, and milkweeds found throughout the colony's range. Like many other members of the genus, Bombus ternarius exhibits complex social structure with a reproductive queen caste and a multitude of sister workers with labor such as foraging, nursing, and nest maintenance divided among the subordinates.

Nuptial flight is an important phase in the reproduction of most ant, termite, and some bee species. It is also observed in some fly species, such as Rhamphomyia longicauda.

Formica polyctena is a species of European red wood ant in the genus Formica and large family Formicidae. The species was first described by Arnold Förster in 1850. The latin species name polyctena is from Greek and literally means 'many cattle', referring to the species' habit of farming aphids for honeydew food. It is found in many European countries. It is a eusocial species, that has a distinct caste system of sterile workers and a very small reproductive caste. The ants have a genetic based cue that allow them to identify which other ants are members of their nest and which are foreign individuals. When facing these types of foreign invaders the F. polyctena has a system to activate an alarm. It can release pheromones which can trigger an alarm response in other nearby ants.

Eusociality is the highest level of organization of sociality [by what metric?]. It is defined by the following characteristics: cooperative brood care, overlapping generations within a colony of adults, and a division of labor into reproductive and non-reproductive groups. The division of labor creates specialized behavioral groups within an animal society which are sometimes referred to as 'castes'. Eusociality is distinguished from all other social systems because individuals of at least one caste usually lose the ability to perform behaviors characteristic of individuals in another caste. Eusocial colonies can be viewed as superorganisms.

Monogyny is a specialised mating system in which a male can only mate with one female throughout his lifetime, but the female may mate with more than one male. In this system, the males generally provide no paternal care. In many spider species that are monogynous, the males have two copulatory organs, which allows them to mate a maximum of twice throughout their lifetime. As is commonly seen in honeybees, ants and certain spider species, a male may put all his energy into a single copulation, knowing that this will lower his overall fitness. During copulation, monogynous males have adapted to cause self genital damage or even death to increase their chances of paternity.

Polistes metricus is a wasp native to North America. In the United States, it ranges throughout the southern Midwest, the South, and as far northeast as New York, but has recently been spotted in southwest Ontario. A single female specimen has also been reported from Dryden, Maine. P. metricus is dark colored, with yellow tarsi and black tibia. Nests of P. metricus can be found attached to the sides of buildings, trees, and shrubbery.

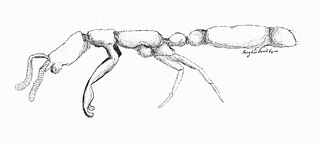

Leptanilla japonica is an uncommon highly migratory, subterranean ant found in Japan. They are tiny insects, with workers measuring about 1.2 mm and queens reaching to about 1.8 mm, and live in very small colonies of only a few hundred individuals at a time Its sexual development follows a seasonal cycle that affects the colony's migration and feeding habits, and vice versa. L. japonica exhibits specialized predation, with prey consisting mainly of geophilomorph centipedes, a less reliable food source that also contributes to their high rate of nest migration. Like ants of genera Amblyopone and Proceratium, the genus Leptanilla engages in larval hemolymph feeding (LHF), with the queen using no other form of sustenance. LHF is an advantageous alternative to the more costly cannibalism. Unlike any other ant, however, members of Leptanilla, including L. japonica, have evolved a specialized organ dubbed the “larval hemolymph tap” that reduces the damage LHF inflicts on the larvae. LHF has become this species' main form of nutrition.

The tree wasp is a species of eusocial wasp in the family Vespidae, found in the temperate regions of Eurasia, particularly in western Europe. Despite being called the tree wasp, it builds both aerial and underground paper nests, and can be found in rural and urban habitats. D. sylvestris is a medium-sized wasp that has yellow and black stripes and a black dot in the center of its clypeus. It is most common to see this wasp between May and September during its 3.5 month colony cycle.

A gamergate is a mated worker ant that can reproduce sexually, i.e., lay fertilized eggs that will develop as females. In the vast majority of ant species, workers are sterile and gamergates are restricted to taxa where the workers have a functional sperm reservoir ('spermatheca'). In some species, gamergates reproduce in addition to winged queens, while in other species the queen caste has been completely replaced by gamergates. In gamergate species, all workers in a colony have similar reproductive potentials, but as a result of physical interactions, a dominance hierarchy is formed and only one or a few top-ranking workers can mate and produce eggs. Subsequently, however, aggression is no longer needed as gamergates secrete chemical signals that inform the other workers of their reproductive status in the colony.

Worker policing is a behavior seen in colonies of social hymenopterans whereby worker females eat or remove eggs that have been laid by other workers rather than those laid by a queen. Worker policing ensures that the offspring of the queen will predominate in the group. In certain species of bees, ants and wasps, workers or the queen may also act aggressively towards fertile workers. Worker policing has been suggested as a form of coercion to promote the evolution of altruistic behavior in eusocial insect societies.

Polistes bellicosus is a social paper wasp from the order Hymenoptera typically found within Texas, namely the Houston area. Like other paper wasps, Polistes bellicosus build nests by manipulating exposed fibers into paper to create cells. P. bellicosus often rebuild their nests at least once per colony season due to predation.

Belonogaster petiolata is a species of primitively eusocial wasp that dwells in southern Africa, in temperate or subhumid climate zones. This wasp species has a strong presence in South Africa and has also been seen in northern Johannesburg. Many colonies can be found in caves. The Sterkfontein Caves in South Africa, for example, contain large populations of B. petiolata.

Protopolybia exigua is a species of vespid wasp found in South America and Southern Brazil. These neotropical wasps, of the tribe Epiponini, form large colonies with multiple queens per colony. P. exigua are small wasps that find nourishment from nectar and prey on arthropods. Their nests are disc-shaped and hang from the undersides of leaves and tree branches. This particular species of wasp can be hard to study because they frequently abandon their nests. P. exigua continuously seek refuge from phorid fly attacks and thus often flee infested nests to build new ones. The wasps' most common predators are ants and the parasitoid phorid flies from the Phoridae family.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Schultner, Eva; d’Ettorre, Patrizia; Helanterä, Heikki (2013). "Social conflict in ant larvae: egg cannibalism occurs mainly in males and larvae prefer alien eggs". Behavioral Ecology. 24 (6): 1306–1311. doi:10.1093/beheco/art067. ISSN 1465-7279.

- ↑ Schultner, Eva; Gardner, Andy; Karhunen, Markku; Helanterä, Heikki (December 2014). "Ant Larvae as Players in Social Conflict: Relatedness and Individual Identity Mediate Cannibalism Intensity". The American Naturalist. 184 (6): E161–E174. doi:10.1086/678459. ISSN 0003-0147. PMID 25438185.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Schultner, Eva (2014). "Cannibalism and conflict in Formica ants". helda.helsinki.fi. Retrieved 2024-08-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Passera, Luc; Aron, Serge (2003-04-01). "Asymétries de parenté et conflits d'intérêt génétique chez les fourmis". Médecine/Sciences (in French). 19 (4): 453–458. doi:10.1051/medsci/2003194453. ISSN 0767-0974. PMID 12836218. Archived from the original on 2023-11-30. Retrieved 2024-08-27.

- ↑ Ratnieks, Francis L.W.; Foster, Kevin R.; Wenseleers, Tom (2006-01-01). "Conflict Resolution in Insect Societies". Annual Review of Entomology. 51 (1): 581–608. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151003. ISSN 0066-4170. PMID 16332224.

- 1 2 3 Brunner, E.; Heinze, J. (2009-11-01). "Worker dominance and policing in the ant Temnothorax unifasciatus". Insectes Sociaux. 56 (4): 397–404. doi:10.1007/s00040-009-0037-x. ISSN 1420-9098.

- ↑ Dobata, Shigeto (2012-08-29). "Arms Race Between Selfishness and Policing: Two-Trait Quantitative Genetic Model for Caste Fate Conflict in Eusocial Hymenoptera". Evolution. 66 (12): 3754–3764. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01745.x. ISSN 0014-3820. PMID 23206134.

- 1 2 André, J. -B.; Peeters, C.; Huet, M.; Doums, C. (2006-05-01). "Estimating the rate of gamergate turnover in the queenless ant Diacamma cyaneiventre using a maximum likelihood model". Insectes Sociaux. 53 (2): 233–240. doi:10.1007/s00040-006-0863-z. ISSN 1420-9098.