Danna, was a Palestinian village 13 kilometres north of Baysan that was captured by the Israel Defense Forces during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, and the villagers were expelled.

Kawfakha' was a Palestinian village located 18 kilometers (11 mi) east of Gaza that was depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

Hamama was a Palestinian town of over 5,000 inhabitants that was depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. It was located 24 kilometers north of Gaza. It was continuously inhabited from the Mamluk period until 1948.

Qula was a Palestinian village in the Ramle Subdistrict of Mandatory Palestine, located 15 km northeast of Ramla. Its residents had their origins in Jimzu, Ammuriya and other places.

Bayt Jirja or Beit Jerja was a Palestinian Arab village 15.5 km Northeast of Gaza. In 1931 the village consisted of 115 houses. It was overrun by Israeli forces during operation Yo'av in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Bayt Jirja was found depopulated in November 1948, during "clean up sweeps" to expel any partial inhabited villages and destroy village housing to prevent any possible re-occupation in the area. The village was completely destroyed after the occupation and only one tomb remains.

al-Tira was a Palestinian town located 7 kilometres south of Haifa. It was made up of five khirbets, including Khirbat al-Dayr where lie the ruins of St. Brocardus monastery and a cave complex with vaulted tunnels.

Miska was a Palestinian village, located fifteen kilometers southwest of Tulkarm, depopulated in 1948.

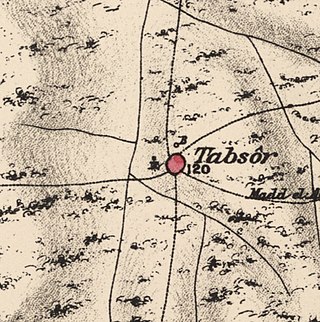

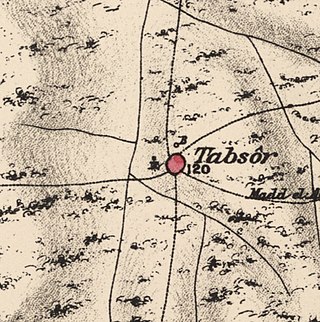

Tabsur, also Khirbat 'Azzun, was a Palestinian village located 19 kilometres southwest of Tulkarm. In 1931, the village had 218 houses and an elementary school for boys. Its Palestinian population was expelled during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war.

Kafr Lam was a Palestinian Arab village located 26 kilometres (16 mi) south of Haifa on the Mediterranean coast. The name of the village was shared with that of an Islamic fort constructed there early in the period of Arab Caliphate rule in Palestine. To the Crusaders, both the fort and the village, which they controlled for some time in the 13th century, were known as Cafarlet.

Bayt Jiz was a Palestinian Arab village situated on undulating land in the western foothills of the Jerusalem heights, 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) southwest of Ramla. In 1945, it had a population of 550. It was occupied by Israeli forces in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and became depopulated.

Bayt Tima was a Palestinian Arab village in the Gaza Subdistrict, located 21 kilometers (13 mi) northeast of Gaza and some 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) from the coastline. It was situated in flat terrain on the southern coastal plain of Palestine. Bayt Tima was depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Its population in 1945 was 1,060.

Kafr Saba was a Palestinian village famous for its shrine dating to the Mamluk period and for a history stretching back for two millennia. In Roman times, it was called Capharsaba and was an important town in Palestine. By around 1000, it was noted as a village with a mosque. The people of Kafr Saba were said to have come from Hebron because of crop failures.

Sarafand al-Ammar was a Palestinian Arab village situated on the coastal plain of Palestine, about 5 kilometers (3.1 mi) northwest of Ramla. It had a population of 1,950 in 1945 and a land area of 13,267 dunams.

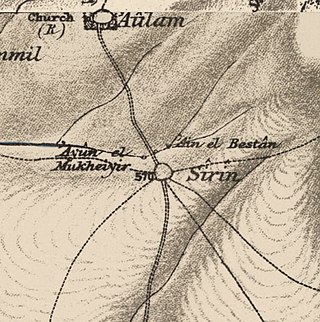

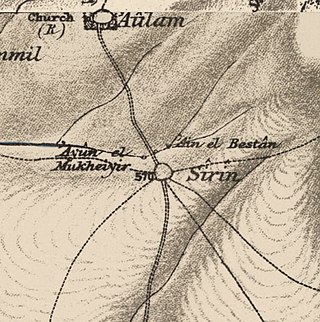

Sirin, was a Palestinian Arab village located 17 kilometers (11 mi) north of Beisan. The village was depopulated and destroyed in 1948. Only the village cemetery and one house remain standing, along with the remains of a mosaic pavement and a vaulted spring dating to the Byzantine period. Mentioned in historical documents, the 1596 census indicated it had 45 households; by 1945, the number of inhabitants had risen to 810.

Ni'ilya was a Palestinian village in the Gaza Subdistrict. It was depopulated during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War on November 4, 1948, under Operation Yo'av. It was located 19 km northeast of Gaza in the city territory of modern Ashkelon. The village was defended by the Egyptian Army.

Al-Haram, was a Palestinian Arab village in the Jaffa Subdistrict, in Mandatory Palestine. It was located 16 km north of Jaffa, adjacent to the ruins of the medieval walled city of Arsuf, and its extent was estimated to range between 9,653 and 11,698 dunams of which 5,150 were accounted for in the cadastral registrations. It was depopulated during the 1948 war.

Al-Safiriyya was a Palestinian Arab village in the Jaffa Subdistrict. It was depopulated during Operation Hametz in the 1948 Palestine War on May 20, 1948. It was located 11 km east of Jaffa, 1.5 km west of Ben Gurion Airport.

Bir Ma'in was a Palestinian Arab village in the Ramle Subdistrict. It was depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War on July 15, 1948 during the second phase of Operation Danny by the First and Second Battalions of the Yiftach Brigade. It was located 14 km east of Ramla. The village was defended by the Jordanian Army.

Dayr Tarif was a Palestinian Arab village in the Ramle Subdistrict of Mandatory Palestine. It was depopulated during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War on July 10, 1948.

Sarafand al-Kharab was a Palestinian Arab village in the Ramle Subdistrict, located 50 meters (160 ft) above sea level, 7 kilometers (4.3 mi) west of Ramla, in the area that is today northeast of Ness Ziona.