Related Research Articles

In grammar, the locative case is a grammatical case which indicates a location. In languages using it, the locative case may perform a function which in English would be expressed with such prepositions as "in", "on", "at", and "by". The locative case belongs to the general local cases, together with the lative and ablative case.

Oromo, historically also called Galla, which is regarded by the Oromo as pejorative, is an Afroasiatic language that belongs to the Cushitic branch. It is native to the Ethiopian state of Oromia and northern Kenya and is spoken predominantly by the Oromo people and neighboring ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa. It is used as a lingua franca particularly in the Oromia Region and northeastern Kenya.

This page describes the declension of nouns, adjectives and pronouns in Slovene. For information on Slovene grammar in general, see Slovene grammar.

Swedish is descended from Old Norse. Compared to its progenitor, Swedish grammar is much less characterized by inflection. Modern Swedish has two genders and no longer conjugates verbs based on person or number. Its nouns have lost the morphological distinction between nominative and accusative cases that denoted grammatical subject and object in Old Norse in favor of marking by word order. Swedish uses some inflection with nouns, adjectives, and verbs. It is generally a subject–verb–object (SVO) language with V2 word order.

Hindustani, the lingua franca of Northern India and Pakistan, has two standardised registers: Hindi and Urdu. Grammatical differences between the two standards are minor but each uses its own script: Hindi uses Devanagari while Urdu uses an extended form of the Perso-Arabic script, typically in the Nastaʿlīq style.

Ukrainian grammar is complex and characterised by a high degree of inflection; moreover, it has a relatively free word order, although the dominant arrangement is subject–verb–object (SVO). Ukrainian grammar describes its phonological, morphological, and syntactic rules. Ukrainian has seven grammatical cases and two numbers for its nominal declension and two aspects, three tenses, three moods, and two voices for its verbal conjugation. Adjectives agree in number, gender, and case with their nouns.

This article describes the grammar of the Scottish Gaelic language.

The grammar of the Marathi language shares similarities with other modern Indo-Aryan languages such as Odia, Gujarati or Punjabi. The first modern book exclusively about the grammar of Marathi was printed in 1805 by Willam Carey.

Punjabi is an Indo-Aryan language native to the region of Punjab of Pakistan and India and spoken by the Punjabi people. This page discusses the grammar of Modern Standard Punjabi as defined by the relevant sources below.

Dirasha is a member of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. It is spoken in the Omo region of Ethiopia, in the hills west of Lake Chamo, around the town of Gidole.

Nepali grammar is the study of the morphology and syntax of Nepali, an Indo-European language spoken in South Asia.

Standard Kannada grammar is primarily based on Keshiraja's Shabdamanidarpana which provides the fullest systematic exposition of Kannada language. The earlier grammatical works include portions of Kavirajamarga of 9th century, Kavyavalokana and Karnatakabhashabhushana both authored by Nagavarma II in first half of the 12th century.

Old Norse has three categories of verbs and two categories of nouns. Conjugation and declension are carried out by a mix of inflection and two nonconcatenative morphological processes: umlaut, a backness-based alteration to the root vowel; and ablaut, a replacement of the root vowel, in verbs.

Historical linguistics has made tentative postulations about and multiple varyingly different reconstructions of Proto-Germanic grammar, as inherited from Proto-Indo-European grammar. All reconstructed forms are marked with an asterisk (*).

Malayalam is one of the Dravidian languages and has an agglutinative grammar. The word order is generally subject–object–verb, although other orders are often employed for reasons such as emphasis. Nouns are inflected for case and number, whilst verbs are conjugated for tense, mood, and causativity. Malayalam adjectives, adverbs, postpositions, and conjunctions do not undergo any inflection; they are invariant.

The morphology of the Polish language is characterised by a fairly regular system of inflection as well as word formation. Certain regular or common alternations apply across the Polish morphological system, affecting word formation and inflection of various parts of speech. These are described below, mostly with reference to the orthographic rather than the phonological system for clarity.

This article concerns the morphology of the Albanian language, including the declension of nouns and adjectives, and the conjugation of verbs. It refers to the Tosk-based Albanian standard regulated by the Academy of Sciences of Albania.

This article describes the grammar of the Old Irish language. The grammar of the language has been described with exhaustive detail by various authors, including Thurneysen, Binchy and Bergin, McCone, O'Connell, Stifter, among many others.

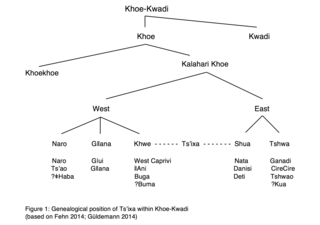

Tsʼixa is a critically endangered African language that belongs to the Kalahari Khoe branch of the Khoe-Kwadi language family. The Tsʼixa speech community consists of approximately 200 speakers who live in Botswana on the eastern edge of the Okavango Delta, in the small village of Mababe. They are a foraging society that consists of the ethnically diverse groups commonly subsumed under the names "San", "Bushmen" or "Basarwa". The most common term of self-reference within the community is Xuukhoe or 'people left behind', a rather broad ethnonym roughly equaling San, which is also used by Khwe-speakers in Botswana. Although the affiliation of Tsʼixa within the Khalari Khoe branch, as well as the genetic classification of the Khoisan languages in general, is still unclear, the Khoisan language scholar Tom Güldemann posits in a 2014 article the following genealogical relationships within Khoe-Kwadi, and argues for the status of Tsʼixa as a language in its own right. The language tree to the right presents a possible classification of Tsʼixa within Khoe-Kwadi:

This page describes the grammar of Maithili language, which has a complex verbal system, nominal declension with a few inflections, and extensive use of honoroficity. It is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Maithili people and is spoken in the Indian state of Bihar with some speakers in Jharkhand and nearby states.The language has a large number of speakers in Nepal too, which is second in number of speakers after Bihar.

References

- ↑ ( Dwyer 1995 , pp. 65–66)

- ↑ ( Dwyer 1995 , p. 282)

- ↑ ( Masica 1991 , p. 213)

- ↑ ( Masica 1991 , p. 473)

- ↑ Taylor 1908, p. 15.

- ↑ ( Tisdall 1892 , p. 27)

- ↑ ( Taylor 1908 , p. 13)

- ↑ ( Masica 1991 , p. 219)

- 1 2 ( Dwyer 1995 , p. 43)

- ↑ ( Masica 1991 , p. 78)

- ↑ ( Dwyer 1995 , pp. 320–321)

- ↑ ( Masica 1991 , p. 234)

- ↑ ( Cardona & Suthar 2003 , pp. 675–676)

- ↑ Masica (1991 :257)

- ↑ ( Masica 1991 , p. 302)

- ↑ ( Masica 1991 , p. 269)

- ↑ ( Dwyer 1995 , p. 149)

- 1 2 3 ( Cardona & Suthar 2003 , p. 680)

- ↑ ( Dwyer 1995 , pp. 88–89)

- ↑ ( Dwyer 1995 , p. 90)

- ↑ ( Dwyer 1995 , pp. 304–306)

- ↑ ( Dwyer 1995 , p. 307)

- ↑ ( Dwyer 1995 , pp. 311–312)

- ↑ ( Dwyer 1995 , pp. 292–294)

- ↑ ( Cardona & Suthar 2003 , p. 686)

- ↑ Grierson, G.A. Linguistic Survey of India: Volume IX, Indo-Aryan FamilY: Central Group, Part II: Specimens of the Rājasthānī and Gujarātī. Superintendent Government Printing. p. 365-366.