Related Research Articles

In grammar, the accusative case of a noun is the grammatical case used to receive the direct object of a transitive verb.

Hebrew is a Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and remained in regular use as a first language until after 200 CE and as the liturgical language of Judaism and Samaritanism. The language was revived as a spoken language in the 19th century, and is the only successful large-scale example of linguistic revival. It is the only Canaanite language, as well as one of only two Northwest Semitic languages, with the other being Aramaic, still spoken today.

A mater lectionis is any consonant that is used to indicate a vowel, primarily in the writing of Semitic languages such as Arabic, Hebrew and Syriac. The letters that do this in Hebrew are aleph א, he ה, waw ו and yod י, with the latter two in particular being more often vowels than they are consonants. In Arabic, the matres lectionis are ʾalif ا, wāw و and yāʾ ي.

An analytic language is a type of natural language in which a series of root/stem words is accompanied by prepositions, postpositions, particles and modifiers, using affixes very rarely. This is opposed to synthetic languages, which synthesize many concepts into a single word, using affixes regularly. Syntactic roles are assigned to words primarily by word order. For example, by changing the individual words in the Latin phrase fēl-is pisc-em cēpit "the cat caught the fish" to fēl-em pisc-is cēpit "the fish caught the cat", the fish becomes the subject, while the cat becomes the object. This transformation is not possible in an analytic language without altering the word order. Typically, analytic languages have a low morpheme-per-word ratio, especially with respect to inflectional morphemes. No natural language, however, is purely analytic or purely synthetic.

The plural, in many languages, is one of the values of the grammatical category of number. The plural of a noun typically denotes a quantity greater than the default quantity represented by that noun. This default quantity is most commonly one. Therefore, plurals most typically denote two or more of something, although they may also denote fractional, zero or negative amounts. An example of a plural is the English word cats, which corresponds to the singular cat.

Elohim, the plural of אֱלוֹהַּ, is a Hebrew word meaning "gods" or "godhood". Although the word is grammatically plural, in the Hebrew Bible it most often takes singular verbal or pronominal agreement and refers to a single deity, particularly the God of Israel. In other verses it refers to the singular gods of other nations or to deities in the plural.

Arabic grammar is the grammar of the Arabic language. Arabic is a Semitic language and its grammar has many similarities with the grammar of other Semitic languages. Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic have largely the same grammar; colloquial spoken varieties of Arabic can vary in different ways.

Phoenician is an extinct Canaanite Semitic language originally spoken in the region surrounding the cities of Tyre and Sidon. Extensive Tyro-Sidonian trade and commercial dominance led to Phoenician becoming a lingua franca of the maritime Mediterranean during the Iron Age. The Phoenician alphabet spread to Greece during this period, where it became the source of all modern European scripts.

Modern Hebrew, also called Israeli Hebrew or simply Hebrew, is the standard form of the Hebrew language spoken today. Developed as part of Hebrew's revival in the late 19th century and early 20th century, it is the official language of the State of Israel, and the world's only Canaanite language in use. Coinciding with the creation of the state of Israel, where it is the national language, Modern Hebrew is the only successful instance of a complete language revival.

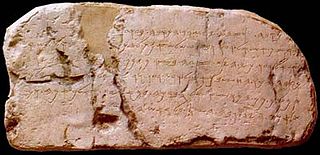

Biblical Hebrew, also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanitic branch of the Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Israel, roughly west of the Jordan River and east of the Mediterranean Sea. The term ʿiḇrîṯ "Hebrew" was not used for the language in the Hebrew Bible, which was referred to as שְֹפַת כְּנַעַן śəp̄aṯ kənaʿan "language of Canaan" or יְהוּדִית Yəhûḏîṯ, "Judean", but it was used in Koine Greek and Mishnaic Hebrew texts.

Ashkenazi Hebrew is the pronunciation system for Biblical and Mishnaic Hebrew favored for Jewish liturgical use and Torah study by Ashkenazi Jewish practice.

Sephardi Hebrew is the pronunciation system for Biblical Hebrew favored for liturgical use by Sephardi Jews. Its phonology was influenced by contact languages such as Spanish and Portuguese, Judaeo-Spanish (Ladino), Judeo-Arabic dialects, and Modern Greek.

Yiddish grammar is the system of principles which govern the structure of the Yiddish language. This article describes the standard form laid out by YIVO while noting differences in significant dialects such as that of many contemporary Hasidim. As a Germanic language descended from Middle High German, Yiddish grammar is fairly similar to that of German, though it also has numerous linguistic innovations as well as grammatical features influenced by or borrowed from Hebrew, Aramaic, and various Slavic languages.

In Hebrew, verbs, which take the form of derived stems, are conjugated to reflect their tense and mood, as well as to agree with their subjects in gender, number, and person. Each verb has an inherent voice, though a verb in one voice typically has counterparts in other voices. This article deals mostly with Modern Hebrew, but to some extent, the information shown here applies to Biblical Hebrew as well.

The revival of the Hebrew language took place in Europe and the Palestine region toward the end of the 19th century and into the 20th century, through which the language's usage changed from purely the sacred language of Judaism to a spoken and written language used for daily life among the Yishuv, and later the State of Israel. Eliezer Ben-Yehuda is often regarded as the "reviver of the Hebrew language" having been the first to raise the concept of reviving Hebrew and initiating a project known as the Ben-Yehuda Dictionary. The revitalization of Hebrew was then ultimately brought about by its usage in Jewish settlement in Ottoman Palestine that arrived in the waves of migration known as the First Aliyah and the Second Aliyah. In Mandatory Palestine, Modern Hebrew became one of three official languages and after the Israeli Declaration of Independence in 1948, one of two official languages of Israel, along with Modern Arabic. In July 2018, a new law made Hebrew the sole official language of the state of Israel, while giving Arabic a "special status".

In linguistics, an inflected preposition is a type of word that occurs in some languages, that corresponds to the combination of a preposition and a personal pronoun. For instance, the Welsh word iddo is an inflected form of the preposition i meaning "to/for him"; it would not be grammatically correct to say *i ef.

Ugaritic is an extinct Northwest Semitic language. This article describes the grammar of the Ugaritic language. For more information regarding the Ugaritic language in general, see Ugaritic language.

The pluralis excellentiae is the name given by early grammarians of Hebrew, such as Wilhelm Gesenius, to a perceived anomaly in the grammatical number and syntax in Hebrew. In some cases it bears some similarity to the pluralis maiestatis or "royal plural". However the idea of excellence is not necessarily present:

Of (c): the pluralis excellentiae or maiestatis, as has been remarked above, is properly a variety of the abstract plural, since it sums up the several characteristics belonging to the idea, besides possessing the secondary sense of an intensification of the original idea. It is thus closely related to the plurals of amplification, treated under e, which are mostly found in poetry.

In Afro-Asiatic languages, the first noun in a genitive phrase that consists of a possessed noun followed by a possessor noun often takes on a special morphological form, which is termed the construct state. For example, in Arabic and Hebrew, the word for "queen" standing alone is malika ملكة and malkaמלכה respectively, but when the word is possessed, as in the phrase "Queen of Sheba", it becomes malikat sabaʾ ملكة سبأ and malkat šəvaמלכת שבא respectively, in which malikat and malkat are the construct state (possessed) form and malikah and malka are the absolute (unpossessed) form. In Geʽez, the word for "queen" is ንግሥት nəgəśt, but in the construct state it is ንግሥተ, as in the phrase "[the] Queen of Sheba" ንግሥታ ሣባ nəgəśta śābā..

The grammar of Modern Hebrew shares similarities with that of its Biblical Hebrew counterpart, but it has evolved significantly over time. Modern Hebrew grammar incorporates analytic, expressing such forms as dative, ablative, and accusative using prepositional particles rather than morphological cases.

References

- ↑ G. Khan, J. B. Noah, The Early Karaite Tradition of Hebrew Grammatical Thought (2000)

- ↑ Pinchas Wechter, Ibn Barūn's Arabic Works on Hebrew Grammar and Lexicography (1964)

- ↑ Online version of De rudimentis hebraicis

- ↑ Grammatica linguae sanctae at Google Books

- ↑ Zuckermann (2006 :74)

- ↑ Rosén (1969)

- 1 2 Glinert (2004 :52)

- ↑ Blau (1981 :153–154)

- ↑ Davis (2007 :536)

- ↑ Doron (2005 :3)

Works cited

- Blau, Joshua (1981). The renaissance of modern Hebrew and modern standard Arabic. University of California Press. ISBN 0520095480.

- Davis, Craig (2007). Dating the Old Testament. New York: RJ Communications. ISBN 978-0-9795062-0-8.

- Doron, Edit (2005), "VSO and Left-conjunct Agreement: Biblical Hebrew vs. Modern Hebrew", in Kiss, Katalin É. (ed.), Universal Grammar in the Reconstruction of Dead Languages (PDF), Berlin: Mouton, pp. 239–264, ISBN 3110185504, archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2011

- Glinert, Lewis (2004). The Grammar of Modern Hebrew. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521611881.

- Rosén, H. (1969). "Israel Language Policy and Linguistics". Ariel. 25: 48–63.