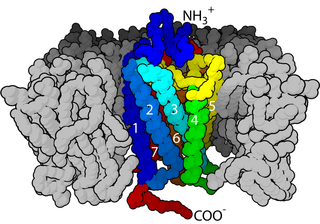

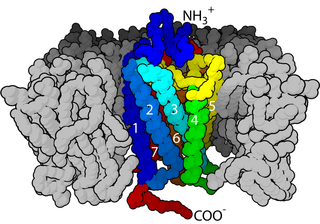

The α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor is an ionotropic transmembrane receptor for glutamate (iGluR) that mediates fast synaptic transmission in the central nervous system (CNS). It has been traditionally classified as a non-NMDA-type receptor, along with the kainate receptor. Its name is derived from its ability to be activated by the artificial glutamate analog AMPA. The receptor was first named the "quisqualate receptor" by Watkins and colleagues after a naturally occurring agonist quisqualate and was only later given the label "AMPA receptor" after the selective agonist developed by Tage Honore and colleagues at the Royal Danish School of Pharmacy in Copenhagen. The GRIA2-encoded AMPA receptor ligand binding core was the first glutamate receptor ion channel domain to be crystallized.

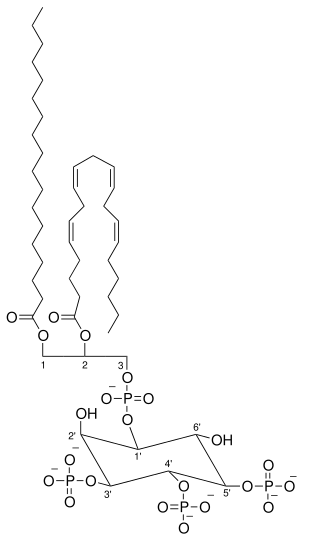

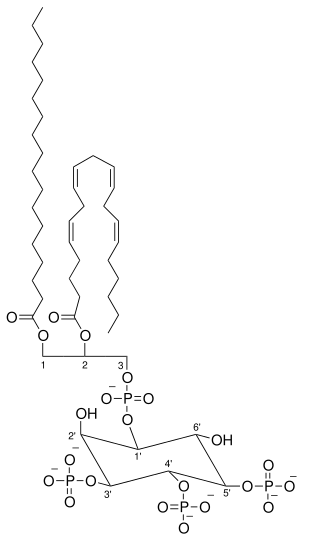

Phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate (PtdIns(3,4,5)P3), abbreviated PIP3, is the product of the class I phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI 3-kinases) phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol (4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2). It is a phospholipid that resides on the plasma membrane.

The postsynaptic density (PSD) is a protein dense specialization attached to the postsynaptic membrane. PSDs were originally identified by electron microscopy as an electron-dense region at the membrane of a postsynaptic neuron. The PSD is in close apposition to the presynaptic active zone and ensures that receptors are in close proximity to presynaptic neurotransmitter release sites. PSDs vary in size and composition among brain regions, and have been studied in great detail at glutamatergic synapses. Hundreds of proteins have been identified in the postsynaptic density, including glutamate receptors, scaffold proteins, and many signaling molecules.

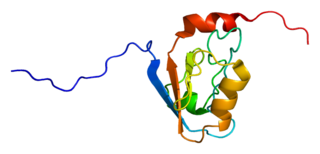

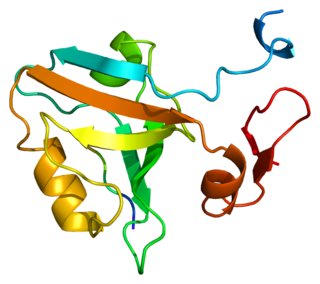

Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 8 (LRP8), also known as apolipoprotein E receptor 2 (ApoER2), is a protein that in humans is encoded by the LRP8 gene. ApoER2 is a cell surface receptor that is part of the low-density lipoprotein receptor family. These receptors function in signal transduction and endocytosis of specific ligands. Through interactions with one of its ligands, reelin, ApoER2 plays an important role in embryonic neuronal migration and postnatal long-term potentiation. Another LDL family receptor, VLDLR, also interacts with reelin, and together these two receptors influence brain development and function. Decreased expression of ApoER2 is associated with certain neurological diseases.

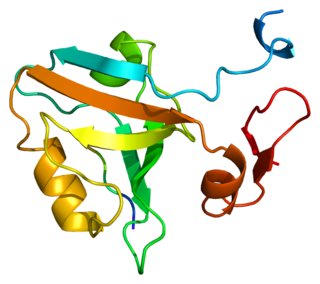

PSD-95 also known as SAP-90 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the DLG4 gene.

Discs large homolog 1 (DLG1), also known as synapse-associated protein 97 or SAP97, is a scaffold protein that in humans is encoded by the SAP97 gene.

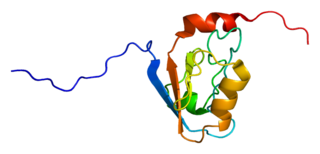

Protein Interacting with C Kinase - 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the PICK1 gene.

Disks large homolog 3 (DLG3) also known as neuroendocrine-DLG or synapse-associated protein 102 (SAP-102) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the DLG3 gene. DLG3 is a member of the membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) superfamily of proteins.

Disks large homolog 2 (DLG2) also known as channel-associated protein of synapse-110 (chapsyn-110) or postsynaptic density protein 93 (PSD-93) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the DLG2 gene.

Syntenin-1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SDCBP gene.

Glutamate [NMDA] receptor subunit epsilon-2, also known as N-methyl D-aspartate receptor subtype 2B, is a protein that in humans is encoded by the GRIN2B gene.

GIPC PDZ domain containing family, member 1 (GIPC1) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the GIPC1 gene. GIPC was originally identified as it binds specifically to the C terminus of RGS-GAIP, a protein involved in the regulation of G protein signaling. GIPC is an acronym for "GAIP Interacting Protein C-terminus". RGS proteins are "Regulators of G protein Signaling" and RGS-GAIP is a "GTPase Activator protein for Gαi/Gαq", which are two major subtypes of Gα proteins. The human GIPC1 molecule is 333 amino acids or about 36 kDa in molecular size and consists of a central PDZ domain, a compact protein module which mediates specific protein-protein interactions. The RGS-GAIP protein interacts with this domain and many other proteins interact here or at other parts of the GIPC1 molecule. As a result, GIPC1 was independently discovered by several other groups and has a variety of alternate names, including synectin, C19orf3, RGS19IP1 and others. The GIPC1 gene family in mammals consisting of three members, so the first discovered, originally named GIPC, is now generally called GIPC1, with the other two being named GIPC2 and GIPC3. The three human proteins are about 60% identical in protein sequence. GIPC1 has been shown to interact with a variety of other receptor and cytoskeletal proteins including the GLUT1 receptor, ACTN1, KIF1B, MYO6, PLEKHG5, SDC4/syndecan-4, SEMA4C/semaphorin-4 and HTLV-I Tax. The general function of GIPC family proteins therefore appears to be mediating specific interactions between proteins involved in G protein signaling and membrane translocation.

Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A member 4 also known as Kv1.4 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the KCNA4 gene. It contributes to the cardiac transient outward potassium current (Ito1), the main contributing current to the repolarizing phase 1 of the cardiac action potential.

Connector enhancer of kinase suppressor of ras 2, also known as CNK homolog protein 2 (CNK2) or maguin, is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the CNKSR2 gene.

Dishevelled (Dsh) is a family of proteins involved in canonical and non-canonical Wnt signalling pathways. Dsh is a cytoplasmic phosphoprotein that acts directly downstream of frizzled receptors. It takes its name from its initial discovery in flies, where a mutation in the dishevelled gene was observed to cause improper orientation of body and wing hairs. There are vertebrate homologs in zebrafish, Xenopus (Xdsh), mice and humans. Dsh relays complex Wnt signals in tissues and cells, in normal and abnormal contexts. It is thought to interact with the SPATS1 protein when regulating the Wnt Signalling pathway.

Cell surface receptors are receptors that are embedded in the plasma membrane of cells. They act in cell signaling by receiving extracellular molecules. They are specialized integral membrane proteins that allow communication between the cell and the extracellular space. The extracellular molecules may be hormones, neurotransmitters, cytokines, growth factors, cell adhesion molecules, or nutrients; they react with the receptor to induce changes in the metabolism and activity of a cell. In the process of signal transduction, ligand binding affects a cascading chemical change through the cell membrane.

Long-term potentiation (LTP), thought to be the cellular basis for learning and memory, involves a specific signal transmission process that underlies synaptic plasticity. Among the many mechanisms responsible for the maintenance of synaptic plasticity is the cadherin–catenin complex. By forming complexes with intracellular catenin proteins, neural cadherins (N-cadherins) serve as a link between synaptic activity and synaptic plasticity, and play important roles in the processes of learning and memory.

Glutamate receptor-interacting protein (GRIP) refers to either a family of proteins that bind to the glutamate receptor or specifically to the GRIP1 protein within this family. Proteins in the glutamate receptor-interacting protein (GRIP) family have been shown to interact with GluR2, a common subunit in the AMPA receptor. This subunit also interacts with other proteins such as protein interacting with C-kinase1 (PICK1) and N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein (NSF). Studies have begun to elucidate its function; however, much is still to be learned about these proteins.

Mary Bernadette Kennedy is an American biochemist and neuroscientist. She is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and is the Allen and Lenabelle Davis Professor of Biology at the California Institute of Technology, where she has been a member of the faculty since 1981. Her research focuses on the molecular mechanisms of synaptic plasticity, the process underlying formation of memory in the central nervous system. Her lab uses biochemical and molecular biological methods to study the protein machinery within a structure called the postsynaptic density. Kennedy has published over 100 papers with over 20,000 total citations.

Synaptic stabilization is crucial in the developing and adult nervous systems and is considered a result of the late phase of long-term potentiation (LTP). The mechanism involves strengthening and maintaining active synapses through increased expression of cytoskeletal and extracellular matrix elements and postsynaptic scaffold proteins, while pruning less active ones. For example, cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) play a large role in synaptic maintenance and stabilization. Gerald Edelman discovered CAMs and studied their function during development, which showed CAMs are required for cell migration and the formation of the entire nervous system. In the adult nervous system, CAMs play an integral role in synaptic plasticity relating to learning and memory.