Columbanus was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries after 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil Abbey in present-day France and Bobbio Abbey in present-day Italy.

Boniface, OSB was an English Benedictine monk and leading figure in the Anglo-Saxon mission to the Germanic parts of the Frankish Empire during the eighth century. He organised significant foundations of the church in Germany and was made archbishop of Mainz by Pope Gregory III. He was martyred in Frisia in 754, along with 52 others, and his remains were returned to Fulda, where they rest in a sarcophagus which has become a site of pilgrimage.

Celtic Christianity is a form of Christianity that was common, or held to be common, across the Celtic-speaking world during the Early Middle Ages. Some writers have described a distinct Celtic Church uniting the Celtic peoples and distinguishing them from adherents of the Roman Church, while others classify Celtic Christianity as a set of distinctive practices occurring in those areas. Varying scholars reject the former notion, but note that there were certain traditions and practices present in both the Irish and British churches that were not seen in the wider Christian world.

Christian monasticism is the devotional practice of Christians who live ascetic and typically cloistered lives that are dedicated to Christian worship. It began to develop early in the history of the Christian Church, modeled upon scriptural examples and ideals, including those in the Old Testament, but not mandated as an institution in the scriptures. It has come to be regulated by religious rules and, in modern times, the Canon law of the respective Christian denominations that have forms of monastic living. Those living the monastic life are known by the generic terms monks (men) and nuns (women). The word monk originated from the Greek μοναχός, itself from μόνος meaning 'alone'.

Lay abbot is a name used to designate a layman on whom a king or someone in authority bestowed an abbey as a reward for services rendered; he had charge of the estate belonging to it, and was entitled to part of the income. The custom existed principally in the Frankish Empire from the eighth century until the ecclesiastical reforms of the eleventh.

Ecgbert was an 8th-century cleric who established the archdiocese of York in 735. In 737, Ecgbert's brother became king of Northumbria and the two siblings worked together on ecclesiastical issues. Ecgbert was a correspondent of Bede and Boniface and the author of a legal code for his clergy. Other works have been ascribed to him, although the attribution is doubted by modern scholars.

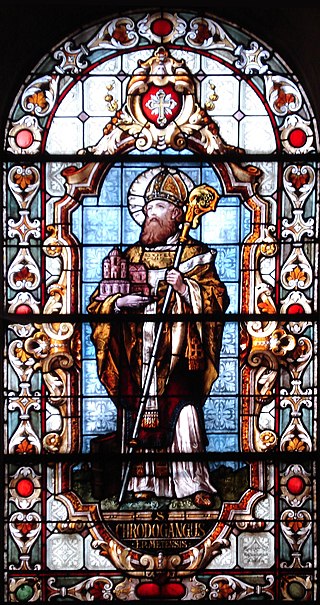

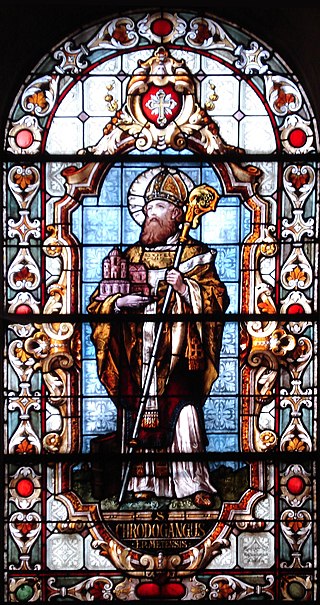

Chrodegang was the Frankish Bishop of Metz from 742 or 748 until his death. He served as chancellor for his kinsman, Charles Martel. Chrodegang is claimed to be a progenitor of the Frankish dynasty of the Robertians. He is recognized as a saint in the Catholic Church

A penitential is a book or set of church rules concerning the Christian sacrament of penance, a "new manner of reconciliation with God" that was first developed by Celtic monks in Ireland in the sixth century AD. It consisted of a list of sins and the appropriate penances prescribed for them, and served as a type of manual for confessors.

Corbie Abbey is a former Benedictine monastery in Corbie, Picardy, France, dedicated to Saint Peter. It was founded by Balthild, the widow of Clovis II, who had monks sent from Luxeuil. The Abbey of Corbie became celebrated both for its library and the scriptorium.

Christianity in Medieval Scotland includes all aspects of Christianity in the modern borders of Scotland in the Middle Ages. Christianity was probably introduced to what is now Lowland Scotland by Roman soldiers stationed in the north of the province of Britannia. After the collapse of Roman authority in the fifth century, Christianity is presumed to have survived among the British enclaves in the south of what is now Scotland, but retreated as the pagan Anglo-Saxons advanced. Scotland was largely converted by Irish missions associated with figures such as St Columba, from the fifth to the seventh centuries. These missions founded monastic institutions and collegiate churches that served large areas. Scholars have identified a distinctive form of Celtic Christianity, in which abbots were more significant than bishops, attitudes to clerical celibacy were more relaxed and there were significant differences in practice with Roman Christianity, particularly the form of tonsure and the method of calculating Easter, although most of these issues had been resolved by the mid-seventh century. After the reconversion of Scandinavian Scotland in the tenth century, Christianity under papal authority was the dominant religion of the kingdom.

Wala was a son of Bernard, son of Charles Martel, and one of the principal advisers of his cousin Charlemagne, of Charlemagne's son Louis the Pious, and of Louis's son Lothair I. He succeeded his brother Adalard as abbot of Corbie and its new daughter foundation, Corvey, in 826 or 827.

The Gregorian mission or Augustinian mission was a Christian mission sent by Pope Gregory the Great in 596 to convert Britain's Anglo-Saxons. The mission was headed by Augustine of Canterbury. By the time of the death of the last missionary in 653, the mission had established Christianity in southern Britain. Along with the Irish and Frankish missions it converted other parts of Britain as well and influenced the Hiberno-Scottish missions to Continental Europe.

Christianity in the 8th century was much affected by the rise of Islam in the Middle East. By the late 8th century, the Muslim empire had conquered all of Persia and parts of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) territory including Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. Suddenly parts of the Christian world were under Muslim rule. Over the coming centuries the Muslim nations became some of the most powerful in the Mediterranean basin.

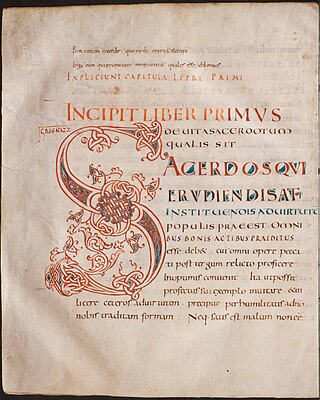

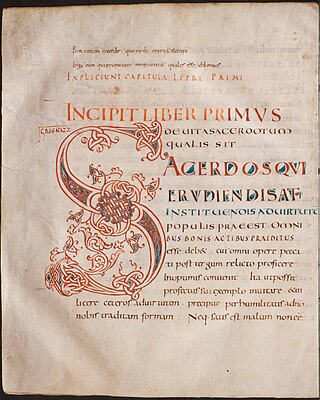

The Collectio canonum quadripartita is an early medieval canon law collection, written around the year 850 in the ecclesiastical province of Reims. It consists of four books. The Quadripartita is an episcopal manual of canon and penitential law. It was a popular source for knowledge of penitential and canon law in France, England and Italy in the ninth and tenth centuries, notably influencing Regino's enormously important Libri duo de synodalibus causis. Even well into the thirteenth century the Quadripartita was being copied by scribes and quoted by canonists who were compiling their own collections of canon law.

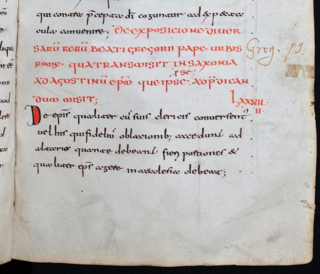

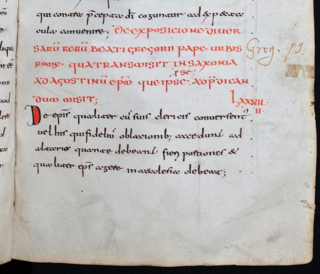

The Libellus responsionum is a papal letter written in 601 by Pope Gregory I to Augustine of Canterbury in response to several of Augustine's questions regarding the nascent church in Anglo-Saxon England. The Libellus was reproduced in its entirety by Bede in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, whence it was transmitted widely in the Middle Ages, and where it is still most often encountered by students and historians today. Before it was ever transmitted in Bede's Historia, however, the Libellus circulated as part of several different early medieval canon law collections, often in the company of texts of a penitential nature.

The Collectio canonum Wigorniensis is a medieval canon law collection originating in southern England around the year 1005. It exists in multiple recensions, the earliest of which — "Recension A" — consists of just over 100 canons drawn from a variety of sources, most predominantly the ninth-century Frankish collection of penitential and canon law known as the Collectio canonum quadripartita. The author of Recension A is currently unknown. Other recensions also exist, slightly later in date than the first. These later recensions are extensions and augmentations of Recension A, and are known collectively as "Recension B". These later recensions all bear the unmistakable mark of having been created by Wulfstan, bishop of Worcester and archbishop of York, possibly sometime around the year 1008, though some of them may have been compiled as late as 1023, the year of Wulfstan's death. The collection treats a range of ecclesiastical and lay subjects, such as clerical discipline, church administration, lay and clerical penance, public and private penance, as well as a variety of spiritual, doctrinal and catechistic matters. Several "canons" in the collection verge on the character of sermons or expository texts rather than church canons in the traditional sense; but nearly every element in the collection is prescriptive in nature, and concerns the proper ordering of society in a Christian polity.

The Bobbio Missal is a seventh-century Christian liturgical codex that probably originated in France.

The Paenitentiale Ecgberhti is an early medieval penitential handbook composed around 740, possibly by Archbishop Ecgberht of York.

The Paenitentiale Bedae is an early medieval penitential handbook composed around 730, possibly by the Anglo-Saxon monk Bede.

The Paenitentiale Theodori is an early medieval penitential handbook based on the judgements of Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury. It exists in multiple versions, the fullest and historically most important of which is the U or Discipulus Umbrensium version, composed (probably) in Northumbria within approximately a decade or two after Theodore's death. Other early though far less popular versions are those known today as the Capitula Dacheriana, the Canones Gregorii, the Canones Basilienses, and the Canones Cottoniani, all of which were compiled before the Paenitentiale Umbrense probably in either Ireland and/or England during or shortly after Theodore's lifetime.