The Algonquian languages are a family of Indigenous languages of the Americas and most of the languages in the Algic language family are included in the group. The name of the Algonquian language family is distinguished from the orthographically similar Algonquin dialect of the Indigenous Ojibwe language (Chippewa), which is a senior member of the Algonquian language family. The term Algonquin has been suggested to derive from the Maliseet word elakómkwik, "they are our relatives/allies".

Tisquantum, more commonly known as Squanto, was a member of the Patuxet tribe of Wampanoags, best known for being an early liaison between the Native American population in Southern New England and the Mayflower Pilgrims who made their settlement at the site of Tisquantum's former summer village, now Plymouth, Massachusetts. The Patuxet tribe had lived on the western coast of Cape Cod Bay, but were wiped out by an epidemic, traditionally assumed to be smallpox brought by previous European explorers; however, recent findings suggest that the disease was Leptospirosis, a bacterial infection transmitted to humans typically via "dirty water" or soil contaminated with the waste product of infected, often domestic animals.

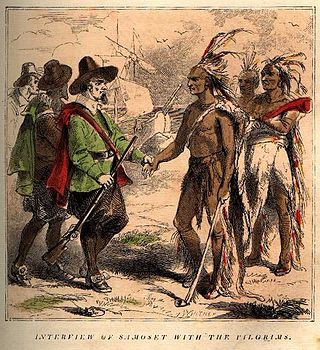

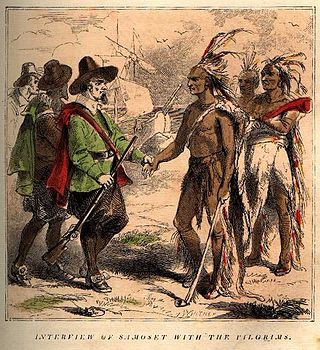

Samoset was an Abenaki sagamore and the first American Indian to make contact with the Pilgrims of Plymouth Colony in New England. He startled the colonists on March 16, 1621 by walking into Plymouth Colony and greeting them in English, saying "Welcome, Englishmen."

Massasoit Sachem or Ousamequin was the sachem or leader of the Wampanoag confederacy. Massasoit means Great Sachem. Although Massasoit was only his title, English colonists mistook it as his name and it stuck.

The Massachusett language is an Algonquian language of the Algic language family that was formerly spoken by several peoples of eastern coastal and southeastern Massachusetts. In its revived form, it is spoken in four Wampanoag communities. The language is also known as Natick or Wôpanâak (Wampanoag), and historically as Pokanoket, Indian or Nonantum.

The Massachusett are a Native American tribe from the region in and around present-day Greater Boston in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The name comes from the Massachusett language term for "At the Great Hill," referring to the Blue Hills overlooking Boston Harbor from the south.

The Eastern Algonquian languages constitute a subgroup of the Algonquian languages. Prior to European contact, Eastern Algonquian consisted of at least 17 languages, whose speakers collectively occupied the Atlantic coast of North America and adjacent inland areas, from what are now the Maritimes of Canada to North Carolina. The available information about individual languages varies widely. Some are known only from one or two documents containing words and phrases collected by missionaries, explorers or settlers, and some documents contain fragmentary evidence about more than one language or dialect. Many of the Eastern Algonquian languages were greatly affected by colonization and dispossession. Miꞌkmaq and Malecite-Passamaquoddy have appreciable numbers of speakers, but Western Abenaki and Lenape (Delaware) are each reported to have fewer than 10 speakers after 2000.

Sachems and sagamores are paramount chiefs among the Algonquians or other Native American tribes of northeastern North America, including the Iroquois. The two words are anglicizations of cognate terms from different Eastern Algonquian languages. Some sources indicate the sagamore was a lesser chief elected by a single band, while the sachem was the head or representative elected by a tribe or group of bands; others suggest the two terms were interchangeable. The positions are elective, not hereditary. Although not strictly hereditary the title of Sachem is often passed through the equivalent of tanistry.

The Nashaway were a tribe of Algonquian Indians inhabiting the upstream portions of the Nashua River valley in what is now the northern half of Worcester County, Massachusetts, mainly in the vicinity of Sterling, Lancaster and other towns near Mount Wachusett, as well as southern New Hampshire. The meaning of Nashaway is "between," an adverbial form derived from "nashau" meaning "someone is between/in the middle" = adverbial suffix "we" Gustafson, Holly (2000), "A Grammar of the Nipmuc Language," University of Manitoba.</ref>

Hobbamock was a Pokanoket pniese who came to live with the Plymouth Colony settlers during the first year of their settlement in North America in 1620. His name was variously spelled in 17th century documents and today is generally simplified as Hobomok. He is known for his rivalry with Squanto, who lived with the settlers before him. He was greatly trusted by Myles Standish, the colony's military commander, and he joined with Standish in a military raid against the Massachuset. Hobomock was also greatly devoted to Massasoit, the sachem of the Pokanoket, who befriended the English settlers. Hobomok is often claimed to have been converted to Christianity, but what that meant to him is unclear.

The Patuxet were a Native American band of the Wampanoag tribal confederation. They lived primarily in and around modern-day Plymouth, Massachusetts, and were among the first Native Americans encountered by European settlers in the region in the early 17th century. Most of the population subsequently died of epidemic infectious diseases. The last of the Patuxet – an individual named Tisquantum, who played an important role in the survival of the Pilgrim colony at Plymouth – died in 1622.

The Agawam were an Algonquian Native American people inhabiting the coast of New England encountered by English colonists who arrived in the early 17th century. Decimated by pestilence shortly before the English colonization and fearing attacks from their hereditary enemies among the Abenaki and other tribes of present-day Maine, they invited the English to settle with them on their tribal territory.

The phonology of the Massachusett language was re-introduced to the Mashpee, Aquinnah, Herring Pond and Assonet tribes that participate in the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project, co-founded by Jessie Little Doe Baird in 1993. The phonology is based regular sound changes that took place in the development of Proto-Eastern Algonquian from Proto-Algonquian, as well as cues in the colonial orthography regarding pronunciation, as the writing system was based on English pronunciation and spelling conventions in use at the time, keeping in mind differences in late seventeenth century English versus today. Other resources included information from extant Algonquian languages with native speakers.

Massachusett writing systems describes the historic and modern systems used for writing Massachusett, an indigenous Algonquian language of the Algic language family. At the time Europeans colonized the region, Massachusett was the primary language of several peoples of New England, including the Massachusett in the area roughly corresponding to Boston, Massachusetts, including much of the Metrowest and South Shore areas just to the west and south of the city; the Wampanoag, who still inhabit Cape Cod and the Islands, most of Plymouth and Bristol counties and south-eastern Rhode Island, including some of the small islands in Narragansett Bay; the Nauset, who may have rather been an isolated Wampanoag sub-group, inhabited the extreme ends of Cape Cod; the Coweset of northern Rhode Island; and the Pawtucket which covered most of northeastern Massachusetts and the lower tributaries of the Merrimack River and coast of New Hampshire, and the extreme southernmost point of Maine. Massachusett was also used as a common second language of peoples throughout New England and Long Island, particularly in a simplified pidgin form.

The Massachusett dialects, as well as all the Southern New England Algonquian (SNEA) languages, could be dialects of a common SNEA language just as Danish, Swedish and Norwegian are mutually intelligible languages that essentially exist in a dialect continuum and three national standards. With the exception of Massachusett, which was adopted as the lingua franca of Christian Indian proselytes and survives in hundreds of manuscripts written by native speakers as well as several extensive missionary works and translations, most of the other SNEA languages are only known from fragmentary evidence, such as place names. Quinnipiac (Quiripey) is only attested in a rough translation of the Lord's Prayer and a bilingual catechism by the English missionary Abraham Pierson in 1658. Coweset is only attested in a handful of lexical items that bear clear dialectal variation after thorough linguistic review of Roger Williams' A Key into the Language of America and place names, but most of the languages are only known from local place names and passing mention of the Native peoples in local historical documents.

The grammar of the Massachusett language shares similarities with the grammars of related Algonquian languages. Nouns have gender based on animacy, based on the Massachusett world-view of what has spirit versus what does not. A body would be animate, but the parts of the body are inanimate. Nouns are also marked for obviation, with nouns subject to the topic marked apart from nouns less relevant to the discourse. Personal pronouns distinguish three persons, two numbers, inclusive and exclusive first-person plural, and proximate/obviative third-persons. Nouns are also marked as absentative, especially when referring to lost items or deceased persons.

Massachusett Pidgin or Massachusett Jargon was a contact pidgin or auxiliary language derived from the Massachusett language attested in the earliest colonial records up until the mid-eighteenth century. Little is known about the language, but it shared a much simplified grammatical system, with many features similar to the better attested Delaware Jargon spoken in the nearby Hudson and Delaware watersheds. It was mutually intelligible with the other Southern New England Algonquian languages.

Southern New England Algonquian cuisine comprises the shared foods and preparation methods of the indigenous Algonquian peoples of the southern half of New England, which consists of Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, but also included portions of coastal New Hampshire and Long Island, now part of New York, as a cultural and culinary region. The peoples of the region historically shared related languages in the Southern New England Algonquian (SNEA) division of the Eastern branch of Algonquian languages as well as related cultures and spiritual practices.

The Wampanoag treaty was a treaty signed on April 1 [O.S. March 22], 1621 between the Wampanoag, led by Massasoit, and the English settlers of Plymouth Colony, led by Governor John Carver.