Progressive education, or educational progressivism, is a pedagogical movement that began in the late 19th century and has persisted in various forms to the present. In Europe, progressive education took the form of the New Education Movement. The term progressive was engaged to distinguish this education from the traditional curricula of the 19th century, which was rooted in classical preparation for the early-industrial university and strongly differentiated by social class. By contrast, progressive education finds its roots in modern, post-industrial experience. Most progressive education programs have these qualities in common:

Learning theory describes how students receive, process, and retain knowledge during learning. Cognitive, emotional, and environmental influences, as well as prior experience, all play a part in how understanding, or a worldview, is acquired or changed and knowledge and skills retained.

Situated learning is a theory that explains an individual's acquisition of professional skills and includes research on apprenticeship into how legitimate peripheral participation leads to membership in a community of practice. Situated learning "takes as its focus the relationship between learning and the social situation in which it occurs".

Student-centered learning, also known as learner-centered education, broadly encompasses methods of teaching that shift the focus of instruction from the teacher to the student. In original usage, student-centered learning aims to develop learner autonomy and independence by putting responsibility for the learning path in the hands of students by imparting to them skills, and the basis on how to learn a specific subject and schemata required to measure up to the specific performance requirement. Student-centered instruction focuses on skills and practices that enable lifelong learning and independent problem-solving. Student-centered learning theory and practice are based on the constructivist learning theory that emphasizes the learner's critical role in constructing meaning from new information and prior experience.

Pedagogy, most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political, and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken as an academic discipline, is the study of how knowledge and skills are imparted in an educational context, and it considers the interactions that take place during learning. Both the theory and practice of pedagogy vary greatly as they reflect different social, political, and cultural contexts.

In education, a curriculum is the totality of student experiences that occur in an educational process. The term often refers specifically to a planned sequence of instruction, or to a view of the student's experiences in terms of the educator's or school's instructional goals. A curriculum may incorporate the planned interaction of pupils with instructional content, materials, resources, and processes for evaluating the attainment of educational objectives. Curricula are split into several categories: the explicit, the implicit, the excluded, and the extracurricular.

Experiential learning (ExL) is the process of learning through experience, and is more narrowly defined as "learning through reflection on doing". Hands-on learning can be a form of experiential learning, but does not necessarily involve students reflecting on their product. Experiential learning is distinct from rote or didactic learning, in which the learner plays a comparatively passive role. It is related to, but not synonymous with, other forms of active learning such as action learning, adventure learning, free-choice learning, cooperative learning, service-learning, and situated learning.

A didactic method is a teaching method that follows a consistent scientific approach or educational style to present information to students. The didactic method of instruction is often contrasted with dialectics and the Socratic method; the term can also be used to refer to a specific didactic method, as for instance constructivist didactics.

Project-based learning is a teaching method that involves a dynamic classroom approach in which it is believed that students acquire a deeper knowledge through active exploration of real-world challenges and problems. Students learn about a subject by working for an extended period of time to investigate and respond to a complex question, challenge, or problem. It is a style of active learning and inquiry-based learning. Project-Based Learning is a form of experiential learning that emphasizes active, hands-on engagement with real-world problems. Project-based learning contrasts with paper-based, rote memorization, or teacher-led instruction that presents established facts or portrays a smooth path to knowledge by instead posing questions, problems, or scenarios.

Outdoor education is organized learning that takes place in the outdoors, such as during school camping trips. Outdoor education programs sometimes involve residential or journey wilderness-based experiences which engage participants in a variety of adventurous challenges and outdoor activities such as hiking, climbing, canoeing, ropes courses and group games. Outdoor education draws upon the philosophy, theory, and practices of experiential education and environmental education.

Reflective practice is the ability to reflect on one's actions so as to take a critical stance or attitude towards one's own practice and that of one's peers, engaging in a process of continuous adaptation and learning. According to one definition it involves "paying critical attention to the practical values and theories which inform everyday actions, by examining practice reflectively and reflexively. This leads to developmental insight". A key rationale for reflective practice is that experience alone does not necessarily lead to learning; deliberate reflection on experience is essential.

Constructivist teaching is based on constructivism. Constructivist teaching is based on the belief that learning occurs as learners are actively involved in a process of meaning and knowledge construction as opposed to passively receiving information.

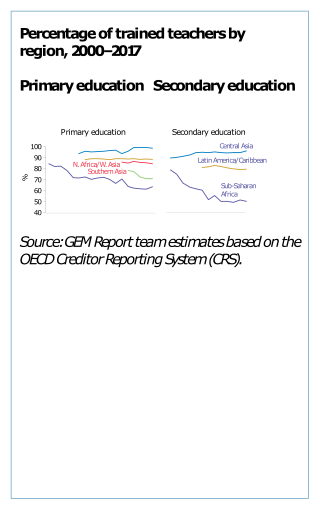

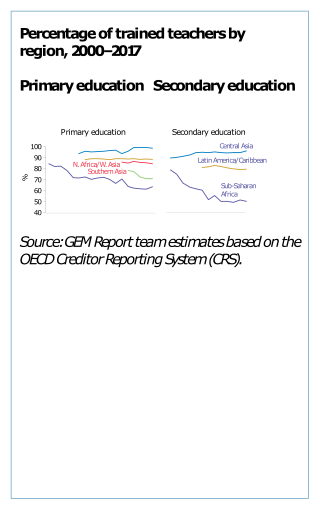

Teacher education or teacher training refers to programs, policies, procedures, and provision designed to equip (prospective) teachers with the knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, approaches, methodologies and skills they require to perform their tasks effectively in the classroom, school, and wider community. The professionals who engage in training the prospective teachers are called teacher educators.

This glossary of education-related terms is based on how they commonly are used in Wikipedia articles. This article contains terms starting with A – C. Select a letter from the table of contents to find terms on other articles.

Inquiry-based learning is a form of active learning that starts by posing questions, problems or scenarios. It contrasts with traditional education, which generally relies on the teacher presenting facts and their knowledge about the subject. Inquiry-based learning is often assisted by a facilitator rather than a lecturer. Inquirers will identify and research issues and questions to develop knowledge or solutions. Inquiry-based learning includes problem-based learning, and is generally used in small-scale investigations and projects, as well as research. The inquiry-based instruction is principally very closely related to the development and practice of thinking and problem-solving skills.

Indigenous education specifically focuses on teaching Indigenous knowledge, models, methods, and content within formal or non-formal educational systems. The growing recognition and use of Indigenous education methods can be a response to the erosion and loss of Indigenous knowledge through the processes of colonialism, globalization, and modernity. Indigenous education also refers to the teaching of the history, culture, and languages of Indigenous peoples of a region.

Learning by doing is a theory that places heavy emphasis on student engagement and is a hands-on, task-oriented, process to education. The theory refers to the process in which students actively participate in more practical and imaginative ways of learning. This process distinguishes itself from other learning approaches as it provides many pedagogical advantages to more traditional learning styles, such those which privilege inert knowledge. Learning-by-doing is related to other types of learning such as adventure learning, action learning, cooperative learning, experiential learning, peer learning, service-learning, and situated learning.

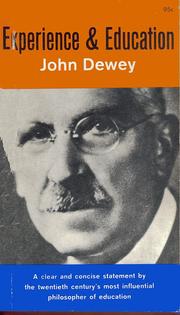

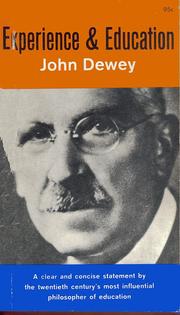

Experience and Education is a short book written in 1938 by John Dewey, a pre-eminent educational theorist of the 20th century. It provides a concise and powerful analysis of education. In this and his other writings on education, Dewey continually emphasizes experience, experiment, purposeful learning, freedom, and other concepts of progressive education. Dewey argues that the quality of an educational experience is critical and stresses the importance of the social and interactive processes of learning.

The term learning environment can refer to an educational approach, cultural context, or physical setting in which teaching and learning occur. The term is commonly used as a more definitive alternative to "classroom", but it typically refers to the context of educational philosophy or knowledge experienced by the student and may also encompass a variety of learning cultures—its presiding ethos and characteristics, how individuals interact, governing structures, and philosophy. In a societal sense, learning environment may refer to the culture of the population it serves and of their location. Learning environments are highly diverse in use, learning styles, organization, and educational institution. The culture and context of a place or organization includes such factors as a way of thinking, behaving, or working, also known as organizational culture. For a learning environment such as an educational institution, it also includes such factors as operational characteristics of the instructors, instructional group, or institution; the philosophy or knowledge experienced by the student and may also encompass a variety of learning cultures—its presiding ethos and characteristics, how individuals interact, governing structures, and philosophy in learning styles and pedagogies used; and the societal culture of where the learning is occurring. Although physical environments do not determine educational activities, there is evidence of a relationship between school settings and the activities that take place there.

Learning space or learning setting refers to a physical setting for a learning environment, a place in which teaching and learning occur. The term is commonly used as a more definitive alternative to "classroom," but it may also refer to an indoor or outdoor location, either actual or virtual. Learning spaces are highly diverse in use, configuration, location, and educational institution. They support a variety of pedagogies, including quiet study, passive or active learning, kinesthetic or physical learning, vocational learning, experiential learning, and others. As the design of a learning space impacts the learning process, it is deemed important to design a learning space with the learning process in mind.