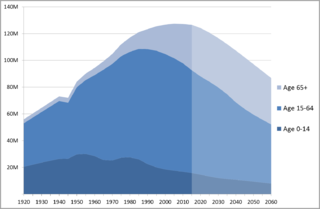

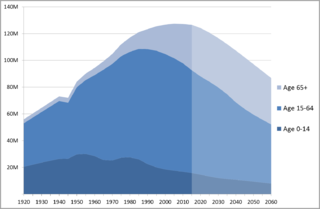

The demographics of China demonstrate a large population with a relatively small youth component, partially a result of China's one-child policy. China's population reached 1 billion in 1982.

This article is about the demographic features of the population of South Korea, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

This article is about the demographic features of the population of Vietnam, including population density, ethnicity, education level, health of the populace, economic status, religious affiliations and other aspects of the population.

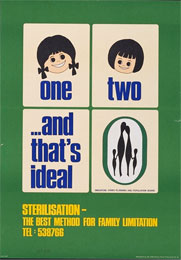

The one-child policy was part of a birth planning program designed to control the size of the rapidly growing population of the People's Republic of China. Distinct from the family planning policies of most other countries, which focus on providing contraceptive options to help women have the number of children they want, it set a limit on the number of births parents could have, making it the world's most extreme example of population planning. It was introduced in 1979, modified beginning in the mid 1980s to allow rural parents a second child if the first was a daughter, and then lasted three more decades before the government announced in late 2015 a reversion to a two-child limit. The policy also allowed exceptions for some other groups, including ethnic minorities. Thus, the term "one-child policy" has been called a "misnomer", because for nearly 30 of the 36 years that it existed (1979–2015), about half of all parents in China were allowed to have a second child.

Human reproduction planning is the practice of intentionally controlling the rate of growth of a human population. Historically, human population planning has been implemented with the goal of increasing the rate of human population growth. However, in the period from the 1950s to the 1980s, concerns about global population growth and its effects on poverty, environmental degradation and political stability led to efforts to reduce human population growth rates. More recently, some countries, such as China, Iran, and Spain, have begun efforts to increase their birth rates once again. While population planning can involve measures that improve people's lives by giving them greater control of their reproduction, a few programs, most notably the Chinese government's "one-child policy and two-child policy", have resorted to coercive measures.

Family planning services are “the ability of individuals and couples to anticipate and attain their desired number of children and the spacing and timing of their births. It is achieved through use of contraceptive methods and the treatment of involuntary infertility.” Family planning may involve consideration of the number of children a woman wishes to have, including the choice to have no children and the age at which she wishes to have them. These matters are influenced by external factors such as marital situation, career considerations, financial position, and any disabilities that may affect their ability to have children and raise them. If sexually active, family planning may involve the use of contraception and other techniques to control the timing of reproduction.

The crude birth rate in a period is the total number of live births per 1,000 population divided by the length of the period in years. The number of live births is normally taken from a universal registration system for births; population counts from a census, and estimation through specialized demographic techniques. The birth rate is used to calculate population growth. The estimated average population may be taken as the mid-year population.

The total fertility rate (TFR), sometimes also called the fertility rate, absolute/potential natality, period total fertility rate (PTFR), or total period fertility rate (TPFR) of a population is the average number of children that would be born to a woman over her lifetime if:

- She was to experience the exact current age-specific fertility rates (ASFRs) through her lifetime, and

- She was to survive from childbirth until the end of her reproductive life.

Compulsory sterilization, also known as forced or coerced sterilization, is a term which is used in reference to government-mandated programs which bring about the sterilization of people. Several countries implemented sterilization programs in the early 20th century. Although such programs have been made illegal in most countries of the world, instances of forced or coerced sterilizations persist.

Iran had a comprehensive and effective program of family planning since the beginning of the 1990s. While Iran's population grew at a rate of more than 3% per year between 1956 and 1986, the growth rate began to decline in the late 1980s and early 1990s after the government initiated a major population control program. By 2007 the growth rate had declined to 0.7 percent per year, with a birth rate of 17 per 1,000 persons and a death rate of 6 per 1,000. Reports by the UN show birth control policies in Iran to be effective with the country topping the list of greatest fertility decreases. UN's Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs says that between 1975 and 1980, the total fertility number was 6.5. The projected level for Iran's 2005 to 2010 birth rate is fewer than two.

Abortion in Russia is legal as an elective procedure up to the 12th week of pregnancy, and in special circumstances at later stages. In 1920, the Russian Soviet Republic became the first country in the world in the modern era to allow abortion in all circumstances, but over the course of the 20th century, the legality of abortion changed more than once, with a ban being enacted again from 1936 to 1955. Russia had the highest number of abortions per woman of child-bearing age in the world according to UN data as of 2010. In terms of the total number, in 2009 China reported that it had over 13 million abortions, out of a population of 1.3 billion, compared to the 1.2 million abortions in Russia, out of a population of 143 million people.

Japan has the highest proportion of elderly citizens of any country in the world. The country is experiencing a "super-aging" society both in rural and urban areas. According to 2014 estimates, 33.0% of the Japanese population is above the age of 60, 25.9% are aged 65 or above, and 12.5% are aged 75 or above. People aged 65 and older in Japan make up a quarter of its total population, estimated to reach a third by 2050.

A two-children policy is a government-imposed limit of two children allowed per family or the payment of government subsidies only to the first two children.

Family planning in India is based on efforts largely sponsored by the Indian government. From 1965 to 2009, contraceptive usage has more than tripled and the fertility rate has more than halved, but the national fertility rate in absolute numbers remains high, causing concern for long-term population growth. India adds up to 1,000,000 people to its population every 20 days. Extensive family planning has become a priority in an effort to curb the projected population of two billion by the end of the twenty-first century.

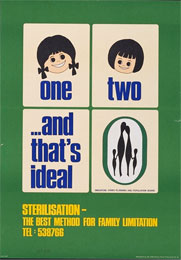

Population planning in Singapore spans two distinct phases: first to slow and reverse the boom in births that started after World War II; and second, from the 1980s onwards, to encourage parents to have more children because birth numbers had fallen below replacement levels.

Fertility factors are determinants of the number of children that an individual is likely to have. Fertility factors are mostly positive or negative correlations without certain causations.

Missing women of China is a widely known phenomenon referring to the unusual shortfall of female population resulting from cultural influences and government policy. The term "missing women" was coined by economist Amartya Sen, winner of the 1998 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, to describe a distorted population sex ratio in which the number of males far outweighed the number of females. Female disadvantages in child survival throughout China reflects a long pattern of sex-based discrimination. Preferences for sons are common in China owing to their ability to carry on family names, their wealth inheritance, and the idea that they are typically the ones to care for their parents once they are older. Limiting the ability for parents to have numerous children forces them to think of logical and long term reasons to have a male or female child. Chinese parents are known to favor large families prefer sons over daughters in effort to create more directed family resources. The result of the discrimination and male preference is a shortfall of women and an extremely unbalanced sex ratio in the population of China.

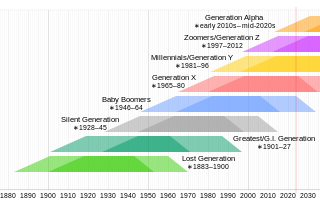

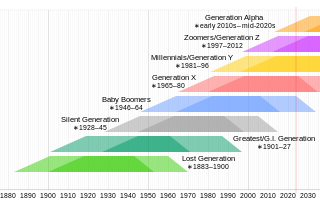

Generation Alpha is the demographic cohort succeeding Generation Z. Researchers and popular media use the early 2010s as the starting birth years and the mid-2020s as the ending birth years. Named after the first letter in the Greek alphabet, Generation Alpha is the first to be born entirely in the 21st century. Most members of Generation Alpha are the children of Millennials.

The low birth rate in South Korea demonstrates the intersection of the low fertility rate in South Korea and government policies. South Korea's birth rate has declined since 1960. Until the 1980s, it was widely believed that this demographic trend would end and that the population would eventually stabilize. However, Korean society faces a decline in its future population because of the continuously decreasing birth rate. After the baby boom in the 1950s, the population increased drastically, and the Korean government implemented an anti-natalistic policy in the 1960s. This government program mandated that Korean healthcare centers provide a family planning consultation by introducing traditional contraception methods, including intrauterine devices (IUDs), vasectomies, and condoms to the public. Along with this policy and economic growth, the fertility rate declined because more married women pursued a higher standard of living rather than raising children. After the economic crisis in 1997, the fertility rate declined rapidly.

Critics of China's treatment of Uyghurs have accused the Chinese government of propagating a policy of sinicization in Xinjiang in the 21st century, calling this policy an ethnocide or a cultural genocide of Uyghurs, with some activists and human rights experts calling it a genocide. In particular, critics have highlighted the concentration of Uyghurs in state-sponsored re-education camps, suppression of Uyghur religious practices, and testimonials of alleged human rights abuses including forced sterilization and contraception. Chinese authorities confirmed that birth rates dropped by almost a third in 2018 in Xinjiang, but denied reports of forced sterilization and genocide.