Etowah Indian Mounds (9BR1) are a 54-acre (220,000 m2) archaeological site in Bartow County, Georgia south of Cartersville, in the United States. Built and occupied in three phases, from 1000–1550 AD, the prehistoric site is located on the north shore of the Etowah River. Etowah Indian Mounds Historic Site is a designated National Historic Landmark, managed by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. It is considered "the most intact Mississippian culture site in the Southeastia ", according to the Georgia State Parks and Historic Sites. It is revered as sacred by the Muscogee Creek and Cherokee peoples, who both occupied this area at varying times.

Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park in present-day Macon, Georgia, United States preserves traces of over ten millennia of culture from the Native Americans in the Southeastern Woodlands. Its chief remains are major earthworks built before 1000 CE by the South Appalachian Mississippian culture These include the Great Temple and other ceremonial mounds, a burial mound, and defensive trenches. They represented highly skilled engineering techniques and soil knowledge, and the organization of many laborers. The site has evidence of "17,000 years of continuous human habitation." The 702-acre (2.84 km2) park is located on the east bank of the Ocmulgee River. Present-day Macon, Georgia developed around the site after the United States built Fort Benjamin Hawkins nearby in 1806 to support trading with Native Americans.

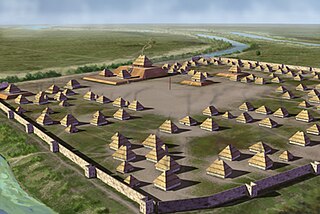

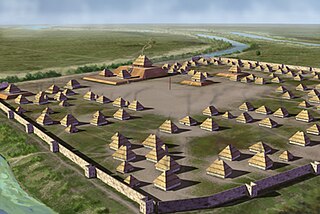

The Mississippian culture was a Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building large, earthen platform mounds, and often other shaped mounds as well. It was composed of a series of urban settlements and satellite villages (suburbs) linked together by loose trading networks. The largest city was Cahokia, believed to be a major religious center located in what is present-day southern Illinois.

Joara was a large Native American settlement, a regional chiefdom of the Mississippian culture, located in what is now Burke County, North Carolina, about 300 miles from the Atlantic coast in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Joara is notable as a significant archaeological and historic site, where Mississippian culture-era and European artifacts have been found, in addition to an earthwork platform mound and remains of a 16th-century Spanish fort.

The Coosa chiefdom was a powerful Native American paramount chiefdom in what are now Gordon and Murray counties in Georgia, in the United States. It was inhabited from about 1400 until about 1600, and dominated several smaller chiefdoms. The total population of Coosa's area of influence, reaching into present-day Tennessee and Alabama, has been estimated at 50,000.

The Fort Walton culture is the term used by archaeologists for a late prehistoric Native American archaeological culture that flourished in southeastern North America from approximately 1200~1500 CE and is associated with the historic Apalachee people.

The Leon-Jefferson Culture is the term used by archaeologists for a protohistoric Native American archaeological culture that flourished in southeastern North America from approximately 1500–1704 CE and is associated with the historic Apalachee people. It was located in and named for the present day Leon and Jefferson counties in northern Florida of the Southeastern United States

The Nodena Site is an archeological site east of Wilson, Arkansas and northeast of Reverie, Tennessee in Mississippi County, Arkansas, United States. Around 1400–1650 CE an aboriginal palisaded village existed in the Nodena area on a meander bend of the Mississippi River. The Nodena site was discovered and first documented by Dr. James K. Hampson, archaeologist and owner of the plantation on which the Nodena site is located. Artifacts from this site are on display in the Hampson Museum State Park in Wilson, Arkansas. The Nodena Site is the type site for the Nodena Phase, believed by many archaeologists to be the province of Pacaha visited by Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto in 1542.

Parkin Archeological State Park, also known as Parkin Indian Mound, is an archeological site and state park in Parkin, Cross County, Arkansas. Around 1350–1650 CE an aboriginal palisaded village existed at the site, at the confluence of the St. Francis and Tyronza rivers. Artifacts from this site are on display at the site museum. The Parkin Site is the type site for the Parkin phase, an expression of the Mississippian culture from the Late Mississippian period. Many archeologists believe it to be part of the province of Casqui, documented as visited by Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto in 1542. Archeological artifacts from the village of the Parkin people are dated to 1400–1650 CE.

Cofitachequi was a paramount chiefdom founded about 1300 AD and encountered by the Hernando de Soto expedition in South Carolina in April 1540. Cofitachequi was later visited by Juan Pardo during his two expeditions (1566–1568) and by Henry Woodward in 1670. Cofitachequi ceased to exist as a political entity prior to 1701.

Chiaha was a Native American chiefdom located in the lower French Broad River valley in modern East Tennessee, in the southeastern United States. They lived in raised structures within boundaries of several stable villages. These overlooked the fields of maize, beans, squash, and tobacco, among other plants which they cultivated. Chiaha was the northern extreme of the paramount Coosa chiefdom's sphere of influence in the 16th century when the Spanish expeditions of Hernando de Soto and Juan Pardo passed through the area. The Chiaha chiefdom included parts of modern Jefferson and Sevier counties, and may have extended westward into Knox, Blount and Monroe counties.

The Plaquemine culture was an archaeological culture centered on the Lower Mississippi River valley. It had a deep history in the area stretching back through the earlier Coles Creek and Troyville cultures to the Marksville culture. The Natchez and related Taensa peoples were their historic period descendants. The type site for the culture is the Medora Site in Louisiana; while other examples include the Anna, Emerald, Holly Bluff, and Winterville sites in Mississippi.

Bussell Island, formerly Lenoir Island, is an island located at the mouth of the Little Tennessee River, at its confluence with the Tennessee River in Loudon County, near the U.S. city of Lenoir City, Tennessee. The island was inhabited by various Native American cultures for thousands of years before the arrival of early European explorers. The Tellico Dam and a recreational area occupy part of the island. Part of the island was added in 1978 to the National Register of Historic Places for its archaeological potential.

The Jere Shine Site (1MT6) is an archaeological site on the Tallapoosa River near its confluence with the Coosa River in modern Montgomery County, Alabama. Based on comparison of archaeological remains and pottery styles, scholars believe that it was most likely occupied from 1400–1550 CE by people of the South Appalachian Mississippian culture.

The Little Egypt site was an archaeological site located in Murray County, Georgia, near the junction of the Coosawattee River and Talking Rock Creek. The site originally had three platform mounds surrounding a plaza and a large village area. It was destroyed during the construction of the Dam of Carters Lake in 1972. It was situated between the Ridge and Valley and Piedmont sections of the state in a flood plain. Using Mississippian culture pottery found at the site archaeologists dated the site to the Middle and Late South Appalachian culture habitation from 1300 to 1600 CE during the Dallas, Lamar, and Mouse Creek phases.

The Dyar site (9GE5) is an archaeological site in Greene County, Georgia, in the north central Piedmont physiographical region. The site covers an area of 2.5 hectares. It was inhabited almost continuously from 1100 to 1600 by a local variation of the Mississippian culture known as the South Appalachian Mississippian culture. Although submerged under Lake Oconee, the site is still important as one of the first explorations of a large Mississippian culture mound. The Dyar site is thought to have been one of the principal towns of the paramount chiefdom of Ocute, perhaps Cofaqui.

The King Archaeological Site (9FL5) is a protohistoric Native American archaeological site located on the Coosa River in Floyd County, Georgia. It is one of 5 large contemporaneous village sites located in a 20 kilometres (12 mi) section of the river. The site was a satellite village associated with the Coosa chiefdom centered on the Little Egypt Site located upstream.

The Carson Mounds,, also known as the Carson Site and Carson-Montgomery- is a large Mississippian culture archaeological site located near Clarksdale in Coahoma County, Mississippi in the Yazoo Basin. Only a few large earthen mounds are still present at Carson to this day. Archaeologists have suggested that Carson is one of the more important archaeological sites in the state of Mississippi.

Ocute, later known as Altamaha or La Tama and sometimes known conventionally as the Oconee province, was a Native American paramount chiefdom in the Piedmont region of the U.S. state of Georgia in the 16th and 17th centuries. Centered in the Oconee River valley, the main chiefdom of Ocute held sway over the nearby chiefdoms of Altamaha, Cofaqui, and possibly others.