A

- Abacus – The Aztec and Maya of Mesoamerica performed arithmetic operations using an abacus. It served as a more accurate and faster alternative to a written solution or relying on memory. Archaeologists have recorded the Mesoamerican abacus, or Nepohualtzintzin, as being present in Mesoamerica from at least between 900 and 1000 CE. [1]

- Abstract art – Abstract art was used by nearly all societies of North and South America. Members of European art world believed tribal art was "primitive" until the 1890s when it served as inspiration for the modern American abstract art movement. [2] See also Visual arts by indigenous peoples of the Americas.

- Adobe – Adobe was used by the peoples from South America, Mesoamerica, and up to Southwestern tribes of the U.S. It is estimated that it was developed around the year 3000 BCE. [3]

- Alcoholic beverages - Several fermented beverages were produced by Native Americans, such as Pulque, Tepache, Agave wine and Cauim. Some of these beverages have gained popularity in modern times, particularly in Mexico. [4]

- Almanacs – Almanacs were invented independently by the Maya peoples. Their culture arose, and presumably began using almanacs, around 3,500 years ago, while Europeans are known to have created written almanacs only after 1150 CE. Almanacs are books containing meteorological and astronomical information, which the Maya used in various aspects of their life. [5]

- Alpacas – Alpacas were domesticated from wild vicuñas approximately 5,000–6,000 years ago in the highlands of the Peruvian Andes near Lake Titicaca. [6]

- Ammassalik wooden maps – The Greenlandic Inuit carved wooden maps that represented coastlines.

- American football – The Iroquois claim to have played football. While no specification is made as to whether this is meant to be American football or soccer, soccer's invention in England in the 1800s is a recent and well documented occurrence.

- Anesthetics – Indigenous peoples used coca, peyote, datura and other plants for partial or total loss of sensation or consciousness during surgery. Western doctors had effective anesthetics only after the mid-19th century. Before this, they either had to perform surgery while the patient dealt with the pain, intoxicated, or they needed to knock the patient out unconscious. [7]

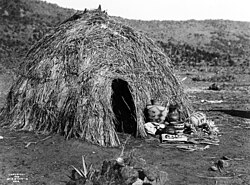

- Apartment blocks – The Ancestral Pueblo people and other tribes which once thrived in the present day Southwest of the US, developed complex multistory apartment complexes, some of which are still in use today. Pueblo communities in present-day New Mexico continue to reside in some of these ancient multistory apartment complexes–which were constructed by their ancestors many centuries ago–even before the first apartments were built in the United States during the 18th century. Pueblo Bonito, one of the seminal archaeological sites today, is an example of this indigenous multistory apartment complex construction from the Anasazi and Hohokam time periods; approximately dating back one thousand years ago.

- Art to be viewed from space – The Nazca Lines were created by the ancient Nazca culture in modern-day Peru. [8] The Nazca built these artworks, which could only be viewed from the sky or from space. It was as if the Nazca were building monuments, which only their gods could view from up in the sky. Some of these artworks, otherwise known as the Nazca Lines, could only be viewed from the sky and each one of these works of Nazca art spans several miles across in size and dimension in the Sechura Desert.

- Aqueducts – The ancient Andean cultures, such as Chimu, Moche and Nazca, lived in dry environments, yet they sustained large scale agriculture consisting of a wide variety of crops by employing aqueducts connecting various freshwater sources, such as mountain streams and lakes to their agricultural fields which were sometimes injecting pressure with the aid of puquios (wind-based water pumps). The Inca later expanded on these previously constructed aqueducts and built a more complex and large aqueduct system in the Inca Empire. The Mesoamerican Aztecs also constructed complex, dual-pipe aqueducts to supply their vast city of Tenochtitlan.

- Aspirin – Indigenous Americans have been using willow tree bark for thousands of years to reduce fever and pain as were the peoples of Assyria, Sumer, Ancient Egypt and Ancient Greece. When chemists analyzed willows in the last century, they discovered salicylic acid; the basis of the modern drug aspirin. [9]

- Asymmetric warfare – Araucanian leaders such as Lautaro developed effective military tactics to counter the Spanish invasion, winning the Arauco War. These tactics consisted in a combination of espionage, cattle raiding, and using attack waves in the battlefield to exhaust the enemy.

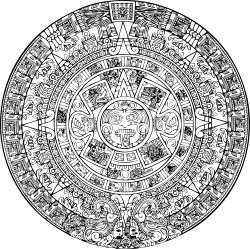

- Astronomy – Mesoamerican cultures, such as the Maya and Aztec, were able to accurately predict astronomical events, like eclipses, hundreds of years into the future. [10]

- Atlatl – Paleo-Indians (Beringian Diaspora) from over 11,500 years ago had developed a highly developed spear thrower in the form of the atlatl to hunt woolly mammoths, giant sloths, mastodon, muskox (euceratherium), giant beaver, early caribou, steppe bison, saber-toothed cat, and other Pleistocene animals. Using the atlatl, these ancient Paleo-Indians were able to traverse much of the Americas from Alaska, down to Mexico, Central America, South America, and, finally, all the way south into Chile as they hunted and followed these Pleistocene megafauna within a short 3,000 year time period–from about 14,500 years ago to about 11,500 years ago. [11]

- Avocado – Indigenous Americans were the first to domesticate and cultivate avocados. [12]