Queer is an umbrella term for people who are not heterosexual or are not cisgender. Originally meaning 'strange' or 'peculiar', queer came to be used pejoratively against those with same-sex desires or relationships in the late 19th century. Beginning in the late 1980s, queer activists, such as the members of Queer Nation, began to reclaim the word as a deliberately provocative and politically radical alternative to the more assimilationist branches of the LGBT community.

Sexuality and gender identity-based cultures are subcultures and communities composed of people who have shared experiences, backgrounds, or interests due to common sexual or gender identities. Among the first to argue that members of sexual minorities can also constitute cultural minorities were Adolf Brand, Magnus Hirschfeld, and Leontine Sagan in Germany. These pioneers were later followed by the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis in the United States.

The LGBT community is a loosely defined grouping of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals united by a common culture and social movements. These communities generally celebrate pride, diversity, individuality, and sexuality. LGBT activists and sociologists see LGBT community-building as a counterweight to heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, sexualism, and conformist pressures that exist in the larger society. The term pride or sometimes gay pride expresses the LGBT community's identity and collective strength; pride parades provide both a prime example of the use and a demonstration of the general meaning of the term. The LGBT community is diverse in political affiliation. Not all people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender consider themselves part of the LGBT community.

Queer studies, sexual diversity studies, or LGBT studies is the study of topics relating to sexual orientation and gender identity usually focusing on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, gender dysphoric, asexual, queer, questioning, and intersex people and cultures.

Heteronormativity is the concept that heterosexuality is the preferred or normal mode of sexual orientation. It assumes the gender binary and that sexual and marital relations are most fitting between people of opposite sex.

Non-heterosexual is a word for a sexual orientation or sexual identity that is not heterosexual. The term helps define the "concept of what is the norm and how a particular group is different from that norm". Non-heterosexual is used in feminist and gender studies fields as well as general academic literature to help differentiate between sexual identities chosen, prescribed and simply assumed, with varying understanding of implications of those sexual identities. The term is similar to queer, though less politically charged and more clinical; queer generally refers to being non-normative and non-heterosexual. Some view the term as being contentious and pejorative as it "labels people against the perceived norm of heterosexuality, thus reinforcing heteronormativity". Still, others say non-heterosexual is the only term useful to maintaining coherence in research and suggest it "highlights a shortcoming in our language around sexual identity"; for instance, its use can enable bisexual erasure.

LGBT themes in speculative fiction include lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) themes in science fiction, fantasy, horror fiction and related genres. Such elements may include an LGBT character as the protagonist or a major character, or explorations of sexuality or gender that deviate from the heteronormative.

Lesbian feminism is a cultural movement and critical perspective that encourages women to focus their efforts, attentions, relationships, and activities towards their fellow women rather than men, and often advocates lesbianism as the logical result of feminism. Lesbian feminism was most influential in the 1970s and early 1980s, primarily in North America and Western Europe, but began in the late 1960s and arose out of dissatisfaction with the New Left, the Campaign for Homosexual Equality, sexism within the gay liberation movement, and homophobia within popular women's movements at the time. Many of the supporters of Lesbianism were actually women involved in gay liberation who were tired of the sexism and centering of gay men within the community and lesbian women in the mainstream women's movement who were tired of the homophobia involved in it.

Lesbian erotica deals with depictions in the visual arts of lesbianism, which is the expression of female-on-female sexuality. Lesbianism has been a theme in erotic art since at least the time of ancient Rome, and many regard depictions of lesbianism to be erotic.

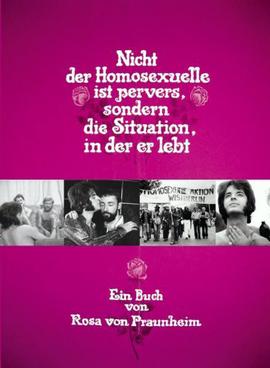

Holger Bernhard Bruno Mischwitzky, known professionally as Rosa von Praunheim, is a German film director, author, painter and one of the most famous gay rights activists in the German-speaking world. In over 50 years, von Praunheim has made more than 150 films. His works influenced the development of LGBTQ+ rights movements worldwide.

Tamsin Elizabeth Wilton was an English lesbian activist, and the UK’s first Professor of Human Sexuality. She researched and wrote extensively about gay and lesbian health, the process of transitioning to lesbianism, and the marginalisation of lesbian issues within sexuality studies.

Historically, the portrayal of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people in media has been largely negative if not altogether absent, reflecting a general cultural intolerance of LGBT individuals; however, from the 1990s to present day, there has been an increase in the positive depictions of LGBT people, issues, and concerns within mainstream media in North America. The LGBT communities have taken an increasingly proactive stand in defining their own culture, with a primary goal of achieving an affirmative visibility in mainstream media. The positive portrayal or increased presence of the LGBT communities in media has served to increase acceptance and support for LGBT communities, establish LGBT communities as a norm, and provide information on the topic.

It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives is a 1971 German avant-garde film directed by Rosa von Praunheim.

Queer pornography depicts performers with various gender identities and sexual orientations interacting and exploring genres of desire and pleasure in unique ways. These conveyed interactions distinctively seek to challenge the conventional modes of portraying and experiencing sexually explicit content. Scholar Ingrid Ryberg additionally includes two main objectives of queer pornography in her definition as "interrogating and troubling gender and sexual categories and aiming at sexual arousal."

Since the transition into the modern-day gay rights movement, homosexuality has appeared more frequently in American film and cinema.

Latin American nations have been producing national LGBT+ cinema since at least the 1980s, though homosexual characters have been appearing in their films since at least 1923.:75 The collection of LGBT-themed films from 2000 onwards has been dubbed New Maricón Cinema by Vinodh Venkatesh; the term both includes Latine culture and identity and does not exclude non-queer LGBT+ films like Azul y no tan rosa.:6-7 Latin American cinema is largely non-systemic, which is established as a reason for its wide variety of LGBT-themed films.:142

The following outline offers an overview and guide to LGBT topics.

Straightwashing is portraying LGB or otherwise queer characters in fiction as heterosexual (straight), making LGB people appear heterosexual, or altering information about historical figures to make their representation comply with heteronormativity.

Homonormativity is the privileging of heteronormative ideals and constructs onto LGBT culture and identity. It is predicated on the assumption that the norms and values of heterosexuality should be replicated and performed among homosexual people. Homonormativity selectively privileges cisgendered homosexuality as worthy of social acceptance.

Queer art, also known as LGBT+ art or queer aesthetics, broadly refers to modern and contemporary visual art practices that draw on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and various non-heterosexual, non-cisgender imagery and issues. While by definition there can be no singular "queer art", contemporary artists who identify their practices as queer often call upon "utopian and dystopian alternatives to the ordinary, adopt outlaw stances, embrace criminality and opacity, and forge unprecedented kinships and relationships." Queer art is also occasionally very much about sex and the embracing of unauthorised desires.