Amalasuintha was a ruler of Ostrogothic Kingdom from 526 to 535. She ruled first as regent for her son Athalaric and thereafter as queen. Amalasuintha was highly educated and was praised by both Cassiodorus, and Procopius for her wisdom and her ability to speak three languages,.

The Ostrogoths were a Roman-era Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Gothic kingdoms within the Roman Empire, based upon the large Gothic populations who had settled in the Balkans in the 4th century, having crossed the Lower Danube. While the Visigoths had formed under the leadership of Alaric I, the new Ostrogothic political entity which came to rule Italy was formed in the Balkans under the influence of the Amal dynasty, the family of Theodoric the Great.

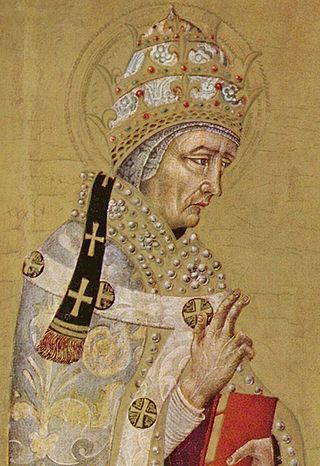

Pope Agapetus I was the bishop of Rome from 13 May 535 to his death. His father, Gordianus, was a priest in Rome and he may have been related to two popes, Felix III and Gregory I.

Pope Silverius was bishop of Rome from 8 June 536 to his deposition in 537, a few months before his death. His rapid rise to prominence from a deacon to the papacy coincided with the efforts of Ostrogothic king Theodahad, who intended to install a pro-Gothic candidate just before the Gothic War. Later deposed by Byzantine general Belisarius, he was tried and sent to exile on the desolated island of Palmarola, where he starved to death in 537.

Pope Symmachus was the bishop of Rome from 22 November 498 to his death. His tenure was marked by a serious schism over who was elected pope by a majority of the Roman clergy.

Pope Hormisdas was the bishop of Rome from 20 July 514 to his death. His papacy was dominated by the Acacian schism, started in 484 by Acacius of Constantinople's efforts to placate the Monophysites. His efforts to resolve this schism were successful, and on 28 March 519, the reunion between Constantinople and Rome was ratified in the cathedral of Constantinople before a large crowd.

Theodahad, also known as Thiudahad was king of the Ostrogoths from 534 to 536.

Dioscorus was a deacon of the Alexandrian and the Roman church from 506. In a disputed election following the death of Pope Felix IV, the majority of electors picked him to be pope, in spite of Pope Felix's wishes that Boniface II should succeed him. However, Dioscorus died less than a month after the election, allowing Boniface to be consecrated pope and Dioscorus to be branded an antipope.

Laurentius was the Archpriest of Santa Prassede and later antipope of the See of Rome. Elected in 498 at the Basilica Saint Mariae with the support of a dissenting faction with Byzantine sympathies, who were supported by Eastern Roman Emperor Anastasius I Dicorus, in opposition to Pope Symmachus, the division between the two opposing factions split not only the church, but the Senate and the people of Rome. However, Laurentius remained in Rome as pope until 506.

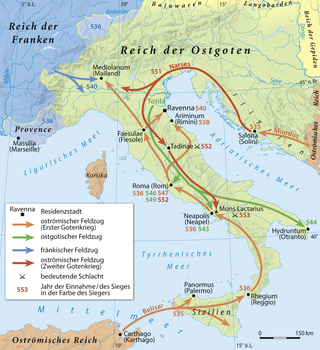

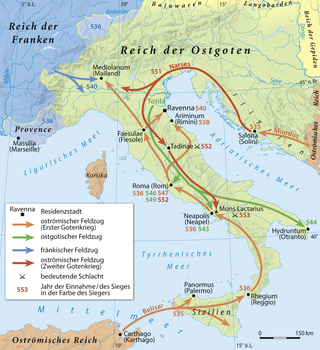

The Gothic War between the Eastern Roman Empire during the reign of Emperor Justinian I and the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy took place from 535 to 554 in the Italian Peninsula, Dalmatia, Sardinia, Sicily and Corsica. It was one of the last of the many Gothic Wars against the Roman Empire. The war had its roots in the ambition of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Emperor Justinian I to recover the provinces of the former Western Roman Empire, which the Romans had lost to invading barbarian tribes in the previous century, during the Migration Period.

The Ostrogothic Kingdom, officially the Kingdom of Italy, existed under the control of the Germanic Ostrogoths in Italy and neighbouring areas from 493 to 553.

The history of the papacy, the office held by the pope as head of the Catholic Church, spans from the time of Peter, to the present day. Moreover, many of the bishops of Rome in the first three centuries of the Christian era are obscure figures. Most of Peter's successors in the first three centuries following his life suffered martyrdom along with members of their flock in periods of persecution.

A Struggle for Rome is a historical novel written by Felix Dahn.

Petrus Marcellinus Felix Liberius was a Late Roman aristocrat and official, whose career spanned seven decades in the highest offices of both the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy and the Eastern Roman Empire. He held the highest governmental offices of Italy, Gaul, and Egypt, "an accomplishment not often recorded – Caesar and Napoleon Bonaparte are the only parallels that come to mind!" as James O'Donnell observes in his biographical study of the man.

The selection of the pope, the bishop of Rome and supreme pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church, prior to the promulgation of In nomine Domini in 1059 varied throughout history. Popes were often appointed by their predecessors or by political rulers. While some kind of election often characterized the procedure, an election that included meaningful participation of the laity was rare, especially as the popes' claims to temporal power solidified into the Papal States. The practice of papal appointment during this period would later result in the jus exclusivae, i.e., a right to veto the selection that Catholic monarchs exercised into the twentieth century.

Eutharic Cilliga was an Ostrogothic prince from Iberia who, during the early 6th century, served as Roman Consul and "son in weapons" alongside the Byzantine emperor Justin I. He was the son-in-law and presumptive heir of the Ostrogoth king Theoderic the Great but died in AD 522 at the age of 42 before he could inherit Theoderic's title. Theoderic claimed that Eutharic was a descendant of the Gothic royal house of Amali and it was intended that his marriage to Theoderic's daughter Amalasuintha would unite the Gothic kingdoms, establish Theoderic's dynasty and further strengthen the Gothic hold over Italy.

The Symmachian forgeries are a sheaf of forged documents produced in the curia of Pope Symmachus (498–514) in the beginning of the sixth century, in the same cycle that produced the Liber Pontificalis. In the context of the conflict between partisans of Symmachus and Antipope Laurentius the purpose of these libelli was to further papal pretensions of the independence of the bishops of Rome from criticisms and judgment of any ecclesiastical tribunal, putting them above law clerical and secular by supplying spurious documents supposedly of an earlier age.

Rufius Petronius Nicomachus Cethegus was a politician of Ostrogothic Italy and the Eastern Roman Empire. He was appointed consul for 504 AD, and held the post without a colleague. His father was Petronius Probinus, the consul for 489 and prominent supporter of Antipope Laurentius.

Caecina Decius Maximus Basilius, was a Roman politician. He was the first consul appointed under Odoacer's rule (480), and afterwards was Praetorian prefect of Italy. He is best known for presiding over the papal election of Pope Felix III.

Rufius Postumius Festus was a Roman aristocrat who lived during the Late Roman Empire. Festus was the last consul appointed by an Emperor in the West. The next consul appointed in the West was Caecina Decius Maximus Basilius, whom king Odoacer appointed in 480, eight years after Festus.