Morphological derivation, in linguistics, is the process of forming a new word from an existing word, often by adding a prefix or suffix, such as -ness or un-. For example, happiness and unhappy derive from the root word happy.

Madí—also known as Jamamadí after one of its dialects, and also Kapaná or Kanamanti (Canamanti)—is an Arawan language spoken by about 1,000 Jamamadi, Banawá, and Jarawara people scattered over Amazonas, Brazil.

Crow is a Missouri Valley Siouan language spoken primarily by the Crow Nation in present-day southeastern Montana. The word, Apsáalooke, translates to "children of the large beaked bird." It is one of the larger populations of American Indian languages with 4,280 speakers according to the 1990 US Census.

Tzeltal or Tsʼeltal is a Mayan language spoken in the Mexican state of Chiapas, mostly in the municipalities of Ocosingo, Altamirano, Huixtán, Tenejapa, Yajalón, Chanal, Sitalá, Amatenango del Valle, Socoltenango, Las Rosas, Chilón, San Juan Cancuc, San Cristóbal de las Casas and Oxchuc. Tzeltal is one of many Mayan languages spoken near this eastern region of Chiapas, including Tzotzil, Chʼol, and Tojolabʼal, among others. There is also a small Tzeltal diaspora in other parts of Mexico and the United States, primarily as a result of unfavorable economic conditions in Chiapas.

Tzotzil is a Maya language spoken by the indigenous Tzotzil Maya people in the Mexican state of Chiapas. Most speakers are bilingual in Spanish as a second language. In Central Chiapas, some primary schools and a secondary school are taught in Tzotzil. Tzeltal is the most closely related language to Tzotzil and together they form a Tzeltalan sub-branch of the Mayan language family. Tzeltal, Tzotzil and Chʼol are the most widely spoken languages in Chiapas.

Halkomelem is a language of various First Nations peoples in British Columbia, ranging from southeastern Vancouver Island from the west shore of Saanich Inlet northward beyond Gabriola Island and Nanaimo to Nanoose Bay and including the Lower Mainland from the Fraser River Delta upriver to Harrison Lake and the lower boundary of the Fraser Canyon.

Wiyot is an extinct Algic language formerly spoken by the Wiyot of Humboldt Bay, California. The language's last native speaker, Delia Prince, died in 1962.

The Tunica language is a language isolate that was spoken in the Central and Lower Mississippi Valley in the United States by Native American Tunica peoples. There are no native speakers of the Tunica language, but as of 2017, there are 32 second language speakers.

Klallam,Clallam, Na'klallam or S'klallam, now extinct, was a Straits Salishan language that was traditionally spoken by the Klallam peoples at Becher Bay on Vancouver Island in British Columbia and across the Strait of Juan de Fuca on the north coast of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington.

The Tonkawa language was spoken in Oklahoma, Texas, and New Mexico by the Tonkawa people. A language isolate, with no known related languages, Tonkawa is now extinct. Members of the Tonkawa tribe now speak English.

Quechan or Kwtsaan, also known as Yuma, is the native language of the Quechan people of southeastern California and southwestern Arizona in the Lower Colorado River Valley and Sonoran Desert.

Wintu is an almost extinct Wintuan language spoken by the Wintu people of Northern California. It is the northernmost member of the Wintun family of languages. The Wintuan family of languages was spoken in the Sacramento River Valley and in adjacent areas up to the Carquinez Strait of San Francisco Bay. Wintun is a branch of the hypothetical Penutian language phylum or stock of languages of western North America, more closely related to four other families of Penutian languages spoken in California: Maiduan, Miwokan, Yokuts, and Costanoan.

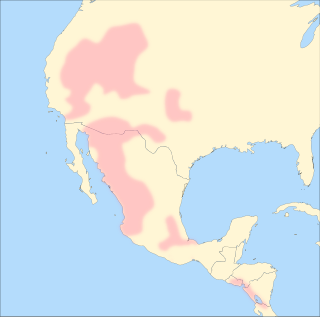

Comanche is a Uto-Aztecan language spoken by the Comanche people, who split off from the Shoshone soon after they acquired horses around 1705. The Comanche language and the Shoshoni language are therefore quite similar, although certain consonant changes in Comanche have inhibited mutual intelligibility.

Natchez was the ancestral language of the Natchez people who historically inhabited Mississippi and Louisiana, and who now mostly live among the Creek and Cherokee peoples in Oklahoma. The language is considered to be either unrelated to other indigenous languages of the Americas or distantly related to the Muskogean languages.

Paumarí is an Arauan language spoken in Brazil by about 300 older adults out of an ethnic population of 900. It is spoken by the Paumari Indians, who call their language “Pamoari”. The word “Pamoari” has several different meanings in the Paumarí language: ‘man,’ ‘people,’ ‘human being,’ and ‘client.’ These multiple meanings stem from their different relationships with outsiders; presumably it means ‘human being’ when they refer to themselves to someone of ostensibly equal status, and ‘client’ when referring to their people among river traders and Portuguese speakers.

Southern Athabascan is a subfamily of Athabaskan languages spoken in the North American Southwest. Refer to Southern Athabascan languages for the main article.

Qʼanjobʼal is a Mayan language spoken primarily in Guatemala and part of Mexico. According to 1998 estimates compiled by SIL International in Ethnologue, there were approximately 77,700 native speakers, primarily in the Huehuetenango Department of Guatemala. Municipalities where the Qʼanjobʼal language is spoken include San Juan Ixcoy, San Pedro Soloma, Santa Eulalia, Santa Cruz Barillas (Yalmotx), San Rafael La Independencia, and San Miguel Acatán. Qʼanjobʼal is taught in public schools through Guatemala's intercultural bilingual education programs.

Bororo (Borôro), also known as Boe, is the sole surviving language of a small family believed to be part of the Macro-Gê languages. It is spoken by the Bororo, hunters and gatherers in the Central Mato Grosso region of Brazil.

Malecite–Passamaquoddy is an endangered Algonquian language spoken by the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy peoples along both sides of the border between Maine in the United States and New Brunswick, Canada. The language consists of two major dialects: Malecite, which is mainly spoken in the Saint John River Valley in New Brunswick; and Passamaquoddy, spoken mostly in the St. Croix River Valley of eastern Maine. However, the two dialects differ only slightly, mainly in accent. Malecite-Passamaquoddy was widely spoken by the indigenous people in these areas until around the post-World War II era, when changes in the education system and increased marriage outside of the speech community caused a large decrease in the number of children who learned or regularly used the language. As a result, in both Canada and the U.S. today, there are only 600 speakers of both dialects, and most speakers are older adults. Although the majority of younger people cannot speak the language, there is growing interest in teaching the language in community classes and in some schools.

Ottawa has complex systems of both inflectional and derivational morphology. Like other dialects of Ojibwe, Ottawa employs complex combinations of inflectional prefixes and suffixes to indicate grammatical information. Ojibwe word stems are formed with combinations of word roots, and affixes referred to as medials and finals to create basic words to which inflectional prefixes and suffixes are added. Word stems are also combined with other word stems to create compound words.