Plato, born Aristocles, was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the written dialogue and dialectic forms. He raised problems for what became all the major areas of both theoretical philosophy and practical philosophy, and was the founder of the Platonic Academy, a philosophical school in Athens where Plato taught the doctrines that would later become known as Platonism.

Parmenides of Elea was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Elea in Magna Graecia.

Ibn Rushd, often Latinized as Averroes, was an Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psychology, mathematics, Islamic jurisprudence and law, and linguistics. The author of more than 100 books and treatises, his philosophical works include numerous commentaries on Aristotle, for which he was known in the Western world as The Commentator and Father of Rationalism.

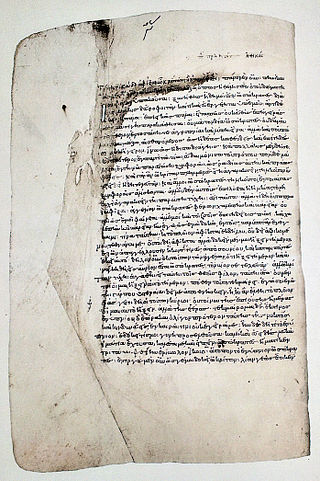

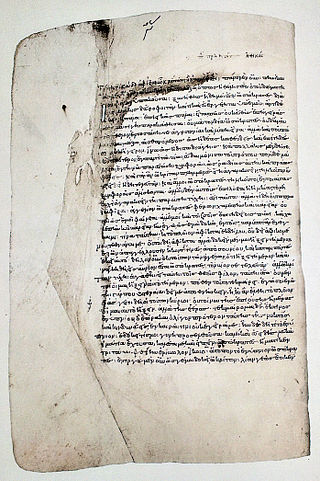

The Theaetetus is a philosophical work written by Plato in the early-middle 4th century BCE that investigates the nature of knowledge, and is considered one of the founding works of epistemology. Like many of Plato's works, the Theaetetus is written in the form of a dialogue, in this case between Socrates and the young mathematician Theaetetus and his teacher Theodorus of Cyrene. In the dialogue, Socrates and Theaetetus attempt to come up with a definition of episteme, or knowledge, and discuss three definitions of knowledge: knowledge as nothing but perception, knowledge as true judgment, and, finally, knowledge as a true judgment with an account. Each of these definitions is shown to be unsatisfactory as the dialogue ends in aporia as Socrates leaves to face a hearing for his trial for impiety.

As a literary technique, an author surrogate is a fictional character based on the author. The author surrogate may be disguised, with a different name, or the author surrogate may be quite close to the author, with the same name. Some authors use author surrogates to express philosophical or political views in the narrative. Authors may also insert themselves under their own name into their works.

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Philosophy was used to make sense of the world using reason. It dealt with a wide variety of subjects, including astronomy, epistemology, mathematics, political philosophy, ethics, metaphysics, ontology, logic, biology, rhetoric and aesthetics. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and later evolved into Roman philosophy.

Mimesis is a term used in literary criticism and philosophy that carries a wide range of meanings, including imitatio, imitation, nonsensuous similarity, receptivity, representation, mimicry, the act of expression, the act of resembling, and the presentation of the self.

Crito is a dialogue that was written by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato. It depicts a conversation between Socrates and his wealthy friend Crito of Alopece regarding justice (δικαιοσύνη), injustice (ἀδικία), and the appropriate response to injustice after Socrates's imprisonment, which is chronicled in the Apology.

In historical scholarship, the Socratic problem concerns attempts at reconstructing a historical and philosophical image of Socrates based on the variable, and sometimes contradictory, nature of the existing sources on his life. Scholars rely upon extant sources, such as those of contemporaries like Aristophanes or disciples of Socrates like Plato and Xenophon, for knowing anything about Socrates. However, these sources contain contradictory details of his life, words, and beliefs when taken together. This complicates the attempts at reconstructing the beliefs and philosophical views held by the historical Socrates. It has become apparent to scholarship that this problem is seemingly impossible to clarify and thus perhaps now classified as unsolvable. Early proposed solutions to the matter still pose significant problems today.

Ancient Greek literature is literature written in the Ancient Greek language from the earliest texts until the time of the Byzantine Empire. The earliest surviving works of ancient Greek literature, dating back to the early Archaic period, are the two epic poems the Iliad and the Odyssey, set in an idealized archaic past today identified as having some relation to the Mycenaean era. These two epics, along with the Homeric Hymns and the two poems of Hesiod, the Theogony and Works and Days, constituted the major foundations of the Greek literary tradition that would continue into the Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman periods.

The Republic is a Socratic dialogue, authored by Plato around 375 BC, concerning justice, the order and character of the just city-state, and the just man. It is Plato's best-known work, and one of the world's most influential works of philosophy and political theory, both intellectually and historically.

The philosopher king is a hypothetical ruler in whom political skill is combined with philosophical knowledge. The concept of a city-state ruled by philosophers is first explored in Plato's Republic, written around 375 BC. Plato argued that the ideal state – one which ensured the maximum possible happiness for all its citizens – could only be brought into being by a ruler possessed of absolute knowledge, obtained through philosophical study. From the Middle Ages onwards, Islamic and Jewish authors expanded on the theory, adapting it to suit their own conceptions of the perfect ruler.

Gregory Paul Currie FAHA is a British philosopher and academic, known for his work on philosophical aesthetics and the philosophy of mind. Currie is Emeritus Professor of Philosophy at the University of York and Executive Editor of Mind & Language.

Irwin Edman was an American philosopher and professor of philosophy.

Christopher Janaway is a philosopher and author. He earned degrees from the University of Oxford. Before moving to Southampton in 2005, Janaway taught at the University of Sydney and Birkbeck, University of London. His recent research has been on Arthur Schopenhauer, Friedrich Nietzsche and aesthetics. His 2007 book Beyond Selflessness: Reading Nietzsche's Genealogy focuses on a critical examination of Nietzsche's On the Genealogy of Morals. Janaway currently lectures at the University of Southampton.

Diotima of Mantinea is the name or pseudonym of an ancient Greek character in Plato's dialogue Symposium, possibly an actual historical figure, indicated as having lived circa 440 B.C. Her ideas and doctrine of Eros as reported by the character of Socrates in the dialogue are the origin of the concept today known as Platonic love.

Socrates was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and as among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no texts and is known mainly through the posthumous accounts of classical writers, particularly his students Plato and Xenophon. These accounts are written as dialogues, in which Socrates and his interlocutors examine a subject in the style of question and answer; they gave rise to the Socratic dialogue literary genre. Contradictory accounts of Socrates make a reconstruction of his philosophy nearly impossible, a situation known as the Socratic problem. Socrates was a polarizing figure in Athenian society. In 399 BC, he was accused of impiety and corrupting the youth. After a trial that lasted a day, he was sentenced to death. He spent his last day in prison, refusing offers to help him escape.

Peter Vaudreuil Lamarque is a British aesthethician and philosopher of art, working in the analytic tradition. Since 2000, he has been a professor of philosophy at the University of York. He is known primarily for his work in philosophy of literature and on the role of emotions in fiction.

Victorino Tejera was a writer, scholar, and professor of philosophy with specializations in ancient Greek thought, Metaphysics, Aesthetics, and American philosophy. He was born in Caracas, Venezuela. He is known especially for his writing on Plato's Dialogues. Many scholars believe Tejera's work in this area is his most valuable contribution to philosophy. He was editor and contributor with Thelma Lavine on History and Anti-History in Philosophy whose FromSocrates to Sartre (1984) was the basis for the PBS series of the same name.