The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I, was the 20th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, held three centuries after the preceding Council of Trent which was adjourned in 1563. The council was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, under the rising threat of the Kingdom of Italy encroaching on the Papal States. It opened on 8 December 1869 and was adjourned on 20 September 1870 after the Italian Capture of Rome. Its best-known decision is its definition of papal infallibility.

The Holy See, also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the pope in his role as head of state or sovereign of the city-state known as the Vatican City, Bishop of Rome, and head of the worldwide Catholic Church. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome, which has ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the city-state of Vatican City and Catholic Church. As the supreme body of government of Vatican City and the Catholic Church, the Holy See holds the status of a sovereign juridical entity under international law.

Vatican City, officially the Vatican City State, is a landlocked sovereign country, city-state, microstate, and enclave within Rome, Italy. It became independent from Italy in 1929 with the Lateran Treaty, and it is a distinct territory under "full ownership, exclusive dominion, and sovereign authority and jurisdiction" of the Holy See, itself a sovereign entity under international law, which maintains the city-state's temporal power and governance, diplomatic, and spiritual independence. The Vatican is also a metonym for the pope, the city-state's and worldwide Catholic Church government Holy See, and Roman Curia.

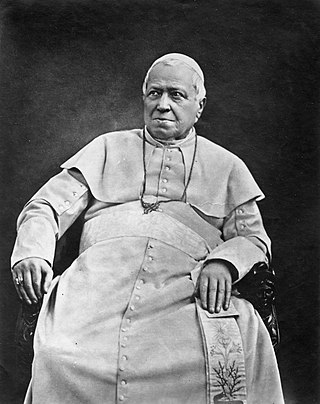

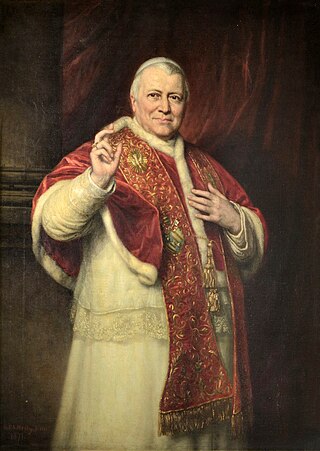

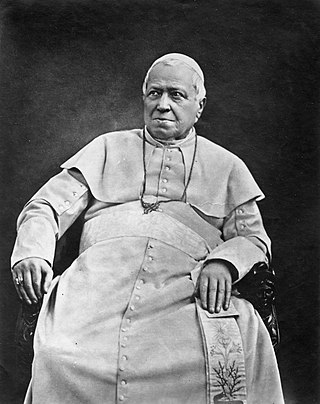

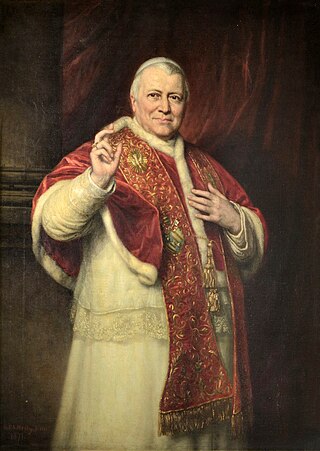

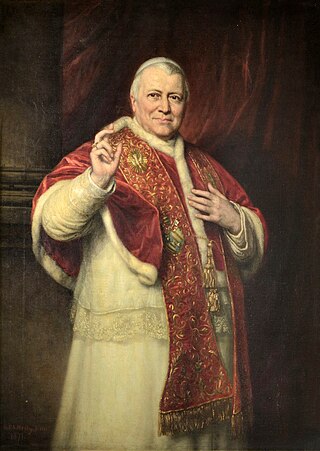

Pope Pius IX was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878. His reign of 32 years is the longest of any pope in history. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican Council in 1868 and for permanently losing control of the Papal States in 1870 to the Kingdom of Italy. Thereafter, he refused to leave Vatican City, declaring himself a "prisoner in the Vatican".

The Papal States, officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the Pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th century until the Unification of Italy, which took place between 1859 and 1870, and culminated in their demise.

The Lateran Treaty was one component of the Lateran Pacts of 1929, agreements between the Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel III and the Holy See under Pope Pius XI to settle the long-standing Roman question. The treaty and associated pacts were named after the Lateran Palace where they were signed on 11 February 1929, and the Italian parliament ratified them on 7 June 1929. The treaty recognised Vatican City as an independent state under the sovereignty of the Holy See. The Italian government also agreed to give the Roman Catholic Church financial compensation for the loss of the Papal States. In 1948, the Lateran Treaty was recognized in the Constitution of Italy as regulating the relations between the state and the Catholic Church. The treaty was significantly revised in 1984, ending the status of Catholicism as the sole state religion.

The Holy See exercised sovereign and secular power, as distinguished from its spiritual and pastoral activity, while the pope ruled the Papal States in central Italy.

A prisoner in the Vatican or prisoner of the Vatican described the situation of the pope with respect to the Kingdom of Italy during the period from the capture of Rome by the Royal Italian Army on 20 September 1870 until the Lateran Treaty of 11 February 1929. Part of the process of the unification of Italy, the city's capture ended the millennium-old temporal rule of the popes over Central Italy and allowed Rome to be designated the capital of the new nation. Although the Italians did not occupy the territories of Vatican Hill delimited by the Leonine walls and offered the creation of a city-state in the area, the popes from Pius IX to Pius XI refused the proposal and described themselves as prisoners of the new Italian state.

Pietro Gasparri was a Roman Catholic cardinal, diplomat and politician in the Roman Curia and the signatory of the Lateran Pacts. He served also as Cardinal Secretary of State under Popes Benedict XV and Pope Pius XI.

The Roman question was a dispute regarding the temporal power of the popes as rulers of a civil territory in the context of the Italian Risorgimento. It ended with the Lateran Pacts between King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and Pope Pius XI in 1929.

The black nobility or black aristocracy are Roman aristocratic families who sided with the Papacy under Pope Pius IX after the Savoy family-led army of the Kingdom of Italy entered Rome on 20 September 1870, overthrew the Pope and the Papal States, and took over the Quirinal Palace, and any nobles subsequently ennobled by the pope prior to the 1929 Lateran Treaty.

Non Expedit were the words with which the Holy See enjoined upon Italian Catholics the policy of boycott from the polls in parliamentary elections.

The Capture of Rome occurred on 20 September 1870, as forces of the Kingdom of Italy took control of the city and of the Papal States. After a plebiscite held on 2 October 1870, Rome was officially made capital of Italy on 3 February 1871, completing the unification of Italy (Risorgimento).

Holy See–Italy relations are the special relations between the Holy See, which is sovereign over the Vatican City, and the Italian Republic.

Vatican during the Savoyard era describes the relation of the Vatican to Italy, after 1870, which marked the end of the Papal States, and 1929, when the papacy regained autonomy in the Lateran Treaty, a period dominated by the Roman Question.

The Holy See has long been recognised as a subject of international law and as an active participant in international relations. It is distinct from the city-state of the Vatican City, over which the Holy See has "full ownership, exclusive dominion, and sovereign authority and jurisdiction".

Papal infallibility is a dogma of the Catholic Church which states that, in virtue of the promise of Jesus to Peter, the Pope when he speaks ex cathedra is preserved from the possibility of error on doctrine "initially given to the apostolic Church and handed down in Scripture and tradition". It does not mean that the pope cannot sin or otherwise err in some capacity, though he is prevented by the assistance of the Holy Spirit from issuing heretical teaching even in his non-infallible Magisterium, as a corollary of indefectibility. This doctrine, defined dogmatically at the First Vatican Council of 1869–1870 in the document Pastor aeternus, is claimed to have existed in medieval theology and to have been the majority opinion at the time of the Counter-Reformation.

Foreign relations between Pope Pius IX and Italy were characterized by an extensive political and diplomatic conflict over Italian unification and the subsequent status of Rome after the victory of the liberal revolutionaries.

The Papal States under Pope Pius IX assumed a much more modern and secular character than had been seen under previous pontificates, and yet this progressive modernization was not nearly sufficient in resisting the tide of political liberalization and unification in Italy during the middle of the 19th century.

The orders, decorations, and medals of the Holy See include titles, chivalric orders, distinctions and medals honoured by the Holy See, with the Pope as the fount of honour, for deeds and merits of their recipients to the benefit of the Holy See, the Catholic Church, or their respective communities, societies, nations and the world at large.