Related Research Articles

Clonmel is the county town and largest settlement of County Tipperary, Ireland. The town is noted in Irish history for its resistance to the Cromwellian army which sacked the towns of Drogheda and Wexford. With the exception of the townland of Suir Island, most of the borough is situated in the civil parish of "St Mary's" which is part of the ancient barony of Iffa and Offa East.

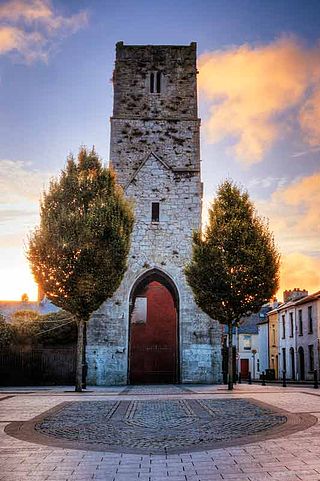

The Red Abbey in Cork, Ireland was a 14th-century Augustinian abbey which took its name from the reddish sandstone used in construction. Today all that remains of the structure is the central bell tower of the abbey church, which is one of the last remaining visible structures dating to the medieval walled town of Cork.

Ormond Castle is a castle on the River Suir on the east side of Carrick-on-Suir, County Tipperary, Ireland. The oldest part of the existing castle is a mid-15th century walled bawn, cornered on the northeast and northwest by towers.

Sliabh Luachra, sometimes anglicised Slieve Logher, is an upland region in Munster, Ireland. It is on the borders of counties Cork, Kerry and Limerick, and bounded to the south by the River Blackwater. It includes the Mullaghareirk Mountains.

Kilmallock is a town in south County Limerick, Ireland, near the border with County Cork. There is a Dominican Priory in the town and King's Castle. The remains of medieval walls which encircled the settlement are still visible.

Fethard is a small town in County Tipperary, Ireland. Dating to the Norman invasion of Ireland, the town's walls were first laid-out in the 13th century, with some sections of these defensive fortifications surviving today.

Sir John Norris, or Norreys, of Rycote, Oxfordshire, and of Yattendon and Notley in Berkshire, was an English soldier. The son of Henry Norris, 1st Baron Norreys, he was a lifelong friend of Queen Elizabeth.

Sir William Drury was an English statesman and soldier.

James Archer (1550–1620) was an Irish Roman Catholic priest of the Society of Jesus who played a highly controversial role in both the Nine Years War and in the military resistance to both the House of Tudor's religious persecution of the Catholic Church in Ireland and the Elizabethan wars against both Gaelic Ireland and the Irish clans. During the final decade of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, Fr. James Archer became a leading figure of hate in the anti-Catholic propaganda of the English government, but his most lasting achievement was his role in the establishment and strengthening of the Irish Colleges in Catholic Europe during the Counter-Reformation.

Dermot O'Hurley —also Dermod or Dermond O'Hurley, Irish: Diarmaid Ó hUrthuile—was an Irish Catholic prelate who served as Archbishop of Cashel during the Tudor conquest of Ireland. After being held and tortured in Dublin Castle, Archbishop O'Hurley was put to death, officially for high treason, but in reality as part of the religious persecution of the Catholic Church in Ireland by Queen Elizabeth I and her officials. He is one of the most celebrated of the 24 formally recognized Irish Catholic Martyrs, and was beatified by Pope John Paul II on 27 September 1992.

Irish Catholic Martyrs were 24 Irish men and women who have been beatified or canonized for dying for their Catholic faith between 1537 and 1681 in Ireland. The canonisation of Oliver Plunkett in 1975 brought an awareness of the others who died for the Catholic faith in the 16th and 17th centuries. On 22 September 1992 Pope John Paul II proclaimed a representative group from Ireland as martyrs and beatified them.

Patrick O'Hely was an Irish Roman Catholic bishop of Mayo, Ireland, who was executed by the English secular authorities.

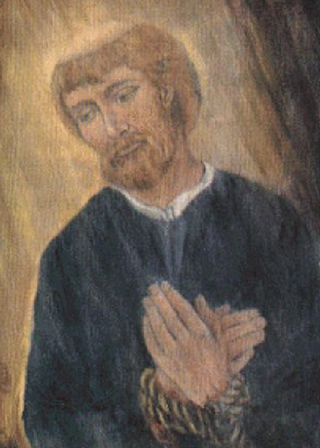

William Tirry OSA was an Irish Roman Catholic priest of the Order of Saint Augustine following the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. He was captured by the priest hunters at Fethard, County Tipperary while continuing his priestly ministry covertly and was hanged at Clonmel, officially for high treason against the Commonwealth of England, but in reality as part of The Protectorate's systematic religious persecution of the Catholic Church in Ireland. Pope John Paul II beatified Friar William Tirry as one of the 24 officially recognized Irish Catholic Martyrs in 1992.

Events from the year 1585 in Ireland.

Le Croisic is a commune in the Loire-Atlantique department, western France. It is part of the urban area of Saint-Nazaire.

Tubrid or Tubbrid was formerly a civil and ecclesiastical parish situated between the towns of Cahir and Clogheen in County Tipperary, Ireland. A cluster of architectural remains at the old settlement still known as Tubrid includes an ancient cemetery and two ruined churches of regional historical significance.

Thomas Fleming was an Irish peer, and a member of the Parliament of Ireland of 1585. He was the son of James Fleming, and great-grandson of James Fleming, 7th Baron Slane. His mother was Ismay Dillon, daughter of Sir Bartholomew Dillon, Lord Chief Justice of Ireland and his first wife Elizabeth Barnewall; after his father's death she remarried Sir Thomas Barnewall of Trimlestown.

St. Patrick's Borstal Institution, Clonmel, was established in Ireland in 1906 as a place of detention for young male offenders aged between 16 and 21, and located in Clonmel, County Tipperary.

Dominic Collins, SJ was an Irish Jesuit lay brother, an ex-soldier, who died for his Catholic faith. He was beatified by Pope John Paul II, along with 16 other Irish Catholic Martyrs, on 27 September 1993.

Ballyneety is a village in County Limerick, Ireland, located approximately 10 km from Limerick city.

References

Notes

- ↑ Profile Archived 2007-11-17 at the Wayback Machine , CatholicIreland.net; accessed 11 December 2015.

- ↑ "Beato Maurizio Mac Kenraghty Sacerdote e martire". santiebeati.it (in Italian).

- ↑ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Page 86.

- ↑ Kinrechtan (MacKenraghty), Maurice, Dictionary of Irish Biography

- ↑ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Page 87.

- ↑ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Page 88.

- ↑ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Page 88.

- ↑ Clonmel Gaol, Tipperary Museum of Hidden History.

- ↑ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Page 88.

- ↑ Kinrechtan (MacKenraghty), Maurice, Dictionary of Irish Biography

- ↑ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Page 88.

- ↑ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Page 88.

- ↑ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Page 88.

- ↑ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Page 89.

- ↑ Clonmel Gaol, Tipperary Museum of Hidden History.

- ↑ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Page 90.

- ↑ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Page 90.

- ↑ Edited by Patrick J. Cornish and Benignus Millet (2005), The Irish Martyrs, Four Courts Press, Dublin. Page 93.

- ↑ Marcus Tanner (2004), The Last of the Celts, Yale University Press. Page 77.

- ↑ Profile Archived 2007-11-17 at the Wayback Machine , CatholicIreland.net; accessed 11 December 2015.

- ↑ "Beato Maurizio Mac Kenraghty Sacerdote e martire". santiebeati.it (in Italian).