Food energy is chemical energy that animals derive from their food to sustain their metabolism, including their muscular activity.

In the U.S. and Canada, the Reference Daily Intake (RDI) is used in nutrition labeling on food and dietary supplement products to indicate the daily intake level of a nutrient that is considered to be sufficient to meet the requirements of 97–98% of healthy individuals in every demographic in the United States. While developed for the US population, it has been adopted by other countries, though not universally.

The Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) is a system of nutrition recommendations from the National Academy of Medicine (NAM) of the National Academies. It was introduced in 1997 in order to broaden the existing guidelines known as Recommended Dietary Allowances. The DRI values differ from those used in nutrition labeling on food and dietary supplement products in the U.S. and Canada, which uses Reference Daily Intakes (RDIs) and Daily Values (%DV) which were based on outdated RDAs from 1968 but were updated as of 2016.

The Food Standards Agency is a non-ministerial government department of the Government of the United Kingdom. It is responsible for protecting public health in relation to food in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. It is led by a board appointed to act in the public interest. Its headquarters are in London, with offices in York, Birmingham, Wales and Northern Ireland. The agency had a national office in Scotland until the formation of Food Standards Scotland in April 2015.

Raisin bran is a breakfast cereal containing raisins and bran flakes. Raisin bran is manufactured by several companies under a variety of brand names, including the popularly known Kellogg's Two Scoops Raisin Bran, General Mills' Total Raisin Bran, and Post Cereals' Raisin Bran. This popular breakfast cereal is a staple in households all over the United States, in part because of its advertised nutritional value.

Milo is a chocolate-flavoured malted powder product produced by Nestlé, typically mixed with milk, hot water, or both, to produce a beverage. It was originally developed in Australia by Thomas Mayne (1901–1995) in 1934.

A healthy diet is a diet that maintains or improves overall health. A healthy diet provides the body with essential nutrition: fluid, macronutrients such as protein, micronutrients such as vitamins, and adequate fibre and food energy.

Plant milk is a plant beverage with a color resembling that of milk. Plant milks are non-dairy beverages made from a water-based plant extract for flavoring and aroma. Plant milks are consumed as alternatives to dairy milk, and may provide a creamy mouthfeel.

A food group is a collection of foods that share similar nutritional properties or biological classifications. Lists of nutrition guides typically divide foods into food groups, and Recommended Dietary Allowance recommends daily servings of each group for a healthy diet. In the United States for instance, the USDA has described food as being in from 4 to 11 different groups.

The nutrition facts label is a label required on most packaged food in many countries, showing what nutrients and other ingredients are in the food. Labels are usually based on official nutritional rating systems. Most countries also release overall nutrition guides for general educational purposes. In some cases, the guides are based on different dietary targets for various nutrients than the labels on specific foods.

Pet food is animal feed intended for consumption by pets. Typically sold in pet stores and supermarkets, it is usually specific to the type of animal, such as dog food or cat food. Most meat used for animals is a byproduct of the human food industry, and is not regarded as "human grade".

Nutrient density identifies the amount of beneficial nutrients in a food product in proportion to e.g. energy content, weight or amount of perceived detrimental nutrients. Terms such as nutrient rich and micronutrient dense refer to similar properties. Several different national and international standards have been developed and are in use.

Food marketing brings together the food producer and the consumer through a chain of marketing activities.

The "jelly bean rule" is a rule put forth by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on May 19, 1994.

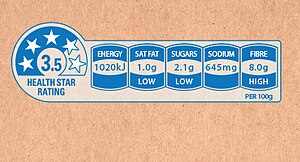

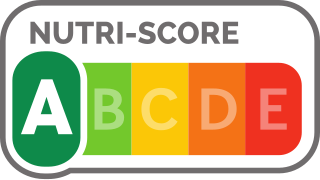

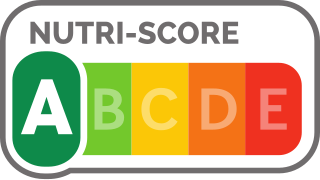

Nutritional rating systems are used to communicate the nutritional value of food in a more-simplified manner, with a ranking, than nutrition facts labels. A system may be targeted at a specific audience. Rating systems have been developed by governments, non-profit organizations, private institutions, and companies. Common methods include point systems to rank foods based on general nutritional value or ratings for specific food attributes, such as cholesterol content. Graphics and symbols may be used to communicate the nutritional values to the target audience.

Federal responsibility for Canadian food labelling requirements is shared between two departments, Health Canada and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). All labelling information that is provided on food labels or in advertisements, as required by legislation, must be accurate, truthful and not misleading. Ingredient lists must accurately reflect the contents and their relative proportions in a food. Nutrition facts tables must accurately reflect the amount of a nutrient present in a food. Net quantity declarations must accurately reflect the amount of food in the package. Certain claims, such as those relating to nutrient content, organic, kosher, halal and certain disease-risk reduction claims, are subject to specific regulatory requirements in addition to the prohibitions in the various acts. For claims that are not subject to specific regulatory requirements, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) and/or Health Canada provide interpretive guidance that assist industry in compliance.

Gerber Products Company is an American purveyor of baby food and baby products headquartered in Florham Park, New Jersey, with plans to relocate to Arlington, Virginia. Gerber is a subsidiary of Nestlé.

Chile's food labelling and advertising law, formally titled Ley 20.606, sobre la composición de los alimentos y su publicidad establishes a regulatory framework on food security and healthy food with the intention of guiding consumers towards behaviour patterns that promote public health. After the 2012 law was enacted, its accompanying regulations came into full force on June 27, 2016. Andrew Jacobs, writing for The New York Times, has characterized this measure as "the world’s most ambitious attempt to remake a country’s food culture" and suggests it "could be a model for how to turn the tide on a global obesity epidemic that researchers say contributes to four million premature deaths a year."

The Nutri-Score, also known as the 5-Colour Nutrition label or 5-CNL, is a five-colour nutrition label and nutritional rating system, and an attempt to simplify the nutritional rating system demonstrating the overall nutritional value of food products. It assigns products a rating letter from A (best) to E (worst), with associated colors from green to red.

Food labeling in Mexico refers to the official norm that mainly consists of placing labels on processed food sold in the country in order to help consumers make a better purchasing decision based on nutritional criteria. The system was approved in 2010 under the Norma Oficial Mexicana (NOM) NOM-051-SCFI/SSA1-2010. The standards, denominated as Daily Dietary Guidelines, were based on the total amount of saturated fats, fats, sodium, sugars and energy or calories represented in kilocalories per package, the percentage they represented per individual portion, as well as the percentage that they would represent in a daily intake.