| Thrombosis prevention, thromboprophylaxis | |

|---|---|

A blood clot blocking a blood vessel. | |

| Other names | Thrombosis prophylaxis |

| ICD-10-PCS | I80-I82 |

| ICD-9-CM | 437.6, 453, 671.5, 671.9 |

Thrombosis prevention or thromboprophylaxis is medical treatment to prevent the development of thrombosis (blood clots inside blood vessels) in those considered at risk for developing thrombosis. [1] Some people are at a higher risk for the formation of blood clots than others, such as those with cancer undergoing a surgical procedure. [2] [3] Prevention measures or interventions are usually begun after surgery as the associated immobility will increase a person's risk. [4]

Contents

- Pathophysiology of blood clot prevention

- Medical treatments

- Epidemiology of developing blood clots

- General risks and indications for blood clot prevention

- Risk for subsequent blood clots

- Well's and modified Well's risk scoring

- Adapted for the emergency department

- General interventions

- Interventions during travel

- Interventions for those hospitalized

- Assessment

- Medication

- Anticoagulants and antiplatelets

- Heparins

- Research

- References

Blood thinners are used to prevent clots, these blood thinners have different effectiveness and safety profiles. A 2018 systematic review found 20 studies that included 9771 people with cancer. The evidence did not identify any difference between the effects of different blood thinners on death, developing a clot, or bleeding. [2] A 2021 review found that low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) was superior to unfractionated heparin in the initial treatment of venous thromboembolism for people with cancer. [3]

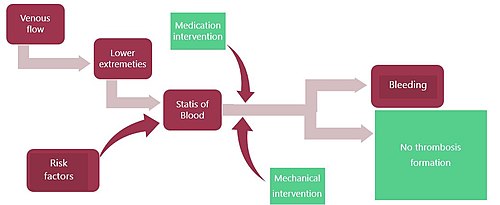

There are medication-based interventions and non-medication-based interventions. [4] The risk of developing blood clots can be lowered by lifestyle modifications, the discontinuation of oral contraceptives, and weight loss. In those at high risk, both interventions are often used. [1] The treatments to prevent the formation of blood clots are balanced against the risk of bleeding. [5]

One of the goals of blood clot prevention is to limit venous stasis as this is a significant risk factor for forming blood clots in the deep veins of the legs. [6] Venous stasis can occur during the long periods of not moving. Thrombosis prevention is also recommended during air travel. [7] Thrombosis prophylaxis is effective in preventing the formation of blood clots, their lodging in the veins, and their developing into thromboemboli that can travel through the circulatory system to cause blockage and subsequent tissue death in other organs. [1] Clarence Crafoord is credited with the first use of thrombosis prophylaxis in the 1930s.