The Congress of the Republic of Peru is the unicameral body that assumes legislative power in Peru. Due to broadly interpreted impeachment wording in the Constitution of Peru, the President of Peru can be removed by Congress without cause, effectively making the legislature more powerful than the executive branch. Following a ruling in February 2023 by the Constitutional Court of Peru, the body tasked with interpreting the Constitution of Peru and whose members are directly chosen by Congress, judicial oversight of the legislative body was also removed by the court, essentially giving Congress absolute control of Peru's government. Since the 2021 Peruvian general election, right wing parties held a majority in the legislature. The largest represented leftist party in Congress, Free Peru, has subsequently aligned itself with conservative and Fujimorists parties within Congress due to their institutional power.

The Political Constitution of Peru is the supreme law of Peru. The current constitution, enacted on 31 December 1993, is Peru's fifth in the 20th century and replaced the 1979 Constitution. The Constitution was drafted by the Democratic Constituent Congress that was convened by President Alberto Fujimori during the Peruvian Constitutional Crisis of 1992 that followed his 1992 dissolution of Congress, was promulgated on 29 December 1993. A Democratic Constitutional Congress (CCD) was elected in 1992, and the final text was approved in a 1993 referendum. The Constitution was primarily created by Fujimori and supporters without the participation of any opposing entities.

Alliance for the Future was a Peruvian electoral alliance formed by pro-Fujimori parties Cambio 90, New Majority and Sí Cumple for the 2006 general election. Its presidential candidate was former President of the Congress and Congresswoman Martha Chávez Cossio.

Keiko Sofía Fujimori Higuchi is a Peruvian politician. Fujimori is the eldest daughter of former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori and Susana Higuchi. From August 1994 to November 2000, she held the role of First Lady of Peru, during her father's administrations. She has served as the leader of the Fujimorist political party Popular Force since 2010, and was a congresswoman representing the Lima Metropolitan Area, from 2006 to 2011. Fujimori ran for president in the 2011, 2016, and 2021 elections, but was defeated each time in the second round of voting.

Alliance for Progress is a Peruvian political party founded on December 8, 2001 in Trujillo by Cesar Acuña Peralta.

Popular Force, known as Force 2011 until 2012, is a right-wing populist and Fujimorist political party in Peru. The party is led by Keiko Fujimori, former congresswoman and daughter of former President Alberto Fujimori. She ran unsuccessfully for the presidency in the 2011, 2016 and 2021 presidential elections, all losing by a narrow margin.

Kenji Gerardo Fujimori Higuchi is a Peruvian businessman, politician and a former congressman representing Lima from 2011 until he was suspended from congressional duty in June 2018, in aftermath of the Mamanivideos scandal. He is the son of former President Alberto Fujimori and former First Lady and congresswoman Susana Higuchi. He has three siblings: Hiro Alberto, Sachi Marcela and Keiko Fujimori. In the 2011 elections, he ran for Congress in the constituency of Lima, under the Force 2011, a Fujimorist political party led by his sister Keiko, being the most voted congressman in 2011. In the 2016 elections, he was re-elected for a second term to Congress, once again representing the same constituency, under the Popular Force, as he received a high number of votes and being the most voted congressman in 2016. In June 2018, following the "Mamanivideos" scandal, Congress suspended Kenji and two other congressmen of his party for allegations of crimes of influence peddling and bribery.

General elections were held in Peru on 10 April 2016 to determine the president, vice-presidents, composition of the Congress of the Republic of Peru and the Peruvian representatives of the Andean Parliament.

Peruvians for Change was a centre-right party in Peru.

On 24 December 2017, the President of Peru, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, pardoned jailed ex-president Alberto Fujimori. Because the pardon was granted on Christmas Eve, it became known as the "indulto de Navidad".

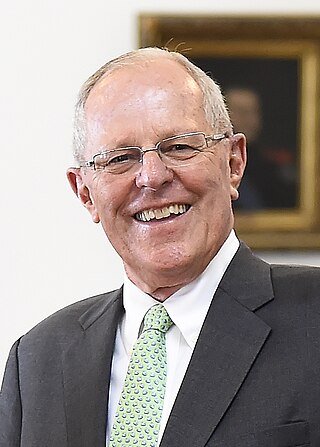

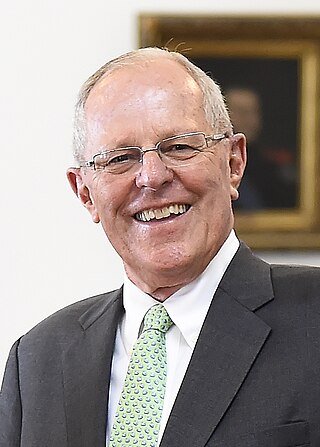

The presidency of Pedro Pablo Kuczynski in Peru began with his inauguration on Peru independence day and ended with the president's resignation following a corruption scandal on March 23, 2018.

Since 2016, Peru has been plagued with political instability and a growing crisis, initially between the President, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and Congress, led de facto by Keiko Fujimori. The crisis emerged in late 2016 and early 2017 as the polarization of Peruvian politics increased, as well as a growing schism between the executive and legislative branches of government. Fujimori and her Fujimorist supporters would use their control of Congress to obstruct the executive branch of successive governments, resulting with a period of political instability in Peru.

Change 21 was a parliamentary group for the congressional term of 2016 to 2021 in the Congress of Peru. The group was introduced on 20 March 2018, led by then-congressman Kenji Fujimori, and was formally recognized on 19 December of the same year by the President of Congress Daniel Salaverry. Its members are former members of Popular Force. The parliamentary group was disbanded following the dissolution of the Congress on 30 September 2019 by President Martin Vizcarra.

General elections were held in Peru on 11 April 2021. The presidential election, which determined the president and the vice presidents, required a run-off between the two top candidates, which was held on 6 June. The congressional elections determined the composition of the Congress of Peru, with all 130 seats contested.

"El ritmo del Chino", sometimes call "El baile del Chino" is a technocumbia song created for the political campaign of the 2000 elections of the Peruvian president and candidate for re-election Alberto Fujimori, who is affectionately nicknamed El Chino as he is of Asian (Japanese) descent.

No to Keiko is a Peruvian non-profit social movement with the objectives of "[making] sure the [Peruvian] population is aware that Keiko [Fujimori] is not a political alternative that can successfully maintain the sustained development of the country," and "defeating the undemocratic establishment of Fujimorism."

Anti-Fujimorism is a political movement characterized by an opposition to Fujimorism, the ideology of former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori and his daughter Keiko Fujimori. The movement has broad support across the political spectrum, with many opponents from the left, center, and right coming out against Fujimorism. The movement properly organized itself after the 1992 Peruvian coup d'état, in which Fujimori illegally gave himself additional powers by unilaterally dissolving the Congress of Peru. Throughout the rest of his reign (1992–2000), the movement strongly opposed the increasingly authoritarian and populist measures of his government. After the end of his rule in November 2000, the anti-Fujimorist coalition has been one of the most influential oppositionary voices in Peruvian general elections, opposing the Fujimorist political parties Peru 2000 in 2000, Cambio 90 – New Majority in 2001, Alliance for the Future in 2006, and Popular Force in 2011, 2016, and 2021.

Su nombre es Fujimori is a documentary film directed by Peruvian Fernando Vílchez that shows a retrospective criticism of Fujimorato. It was part of the campaign for Anti-Fujimorism during the 2016 Peruvian general election.

On 7 December 2022, President of Peru Pedro Castillo attempted to dissolve Congress in the face of imminent impeachment proceedings by the legislative body, immediately enacting a curfew, attempted to establish an emergency government and rule by decree, and called for the formation of a constituent assembly, a violation of Article 206 of the Constitution of Peru. Attorney General Patricia Benavides, had previously claimed that Castillo was the head of a criminal organization and called on Congress to remove him from office, with legislators then attempting a third impeachment of Castillo. Citing the actions of Congress obstructing many of his policies during his administration, Castillo argued that the legislative body served oligopolic businesses and that it had allied itself with the Constitutional Court to destroy the executive branch in an effort to create a "dictatorship of Congress". He also called for the immediate election of a constituent assembly with some calls for the creation of a constituent assembly existing since the 2020 Peruvian protests.

La Resistencia Dios, Patria y Familia, commonly known as La Resistencia, is a far-right militant organization that promotes Fujimorism in Peru.