Coal gas is a flammable gaseous fuel made from coal and supplied to the user via a piped distribution system. It is produced when coal is heated strongly in the absence of air. Town gas is a more general term referring to manufactured gaseous fuels produced for sale to consumers and municipalities.

Fiddlers Ferry Power Station is a decommissioned coal fired power station located in Warrington, Cheshire, England. Opened in 1971, the station had a generating capacity of 1,989 megawatts and took water from the River Mersey. After privatisation in 1990, the station was operated by various companies, and from 2004 to 2022 by SSE Thermal. The power station closed on 31 March 2020. The site was acquired by Peel NRE in July 2022.

Gas Works Park is a park located in Seattle, Washington, United States. It is a 19.1-acre (77,000 m2) public park on the site of the former Seattle Gas Light Company gasification plant, located on the north shore of Lake Union at the south end of the Wallingford neighborhood. The park was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 2, 2013, over a decade after being nominated.

A gas holder or gasholder, also known as a gasometer, is a large container in which natural gas or town gas is stored near atmospheric pressure at ambient temperatures. The volume of the container follows the quantity of stored gas, with pressure coming from the weight of a movable cap. Typical volumes for large gas holders are about 50,000 cubic metres (1,800,000 cu ft), with 60-metre (200 ft) diameter structures.

Sasol Limited is an integrated energy and chemical company based in Sandton, South Africa. The company was formed in 1950 in Sasolburg, South Africa, and built on processes that German chemists and engineers first developed in the early 1900s. Today, Sasol develops and commercializes technologies, including synthetic fuel technologies, and produces different liquid fuels, chemicals, coal tar, and electricity.

A gasworks or gas house is an industrial plant for the production of flammable gas. Many of these have been made redundant in the developed world by the use of natural gas, though they are still used for storage space.

The Gas Retort House at 39 Gas Street, Birmingham, England is the last remaining building of Birmingham's first gas works.

The Gas Light and Coke Company, was a company that made and supplied coal gas and coke. The headquarters of the company were located on Horseferry Road in Westminster, London. It is identified as the original company from which British Gas plc is descended.

The history of gaseous fuel, important for lighting, heating, and cooking purposes throughout most of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, began with the development of analytical and pneumatic chemistry in the 18th century. The manufacturing process for "synthetic fuel gases" typically consisted of the gasification of combustible materials, usually coal, but also wood and oil. The coal was gasified by heating the coal in enclosed ovens with an oxygen-poor atmosphere. The fuel gases generated were mixtures of many chemical substances, including hydrogen, methane, carbon monoxide and ethylene, and could be burnt for heating and lighting purposes. Coal gas, for example, also contains significant quantities of unwanted sulfur and ammonia compounds, as well as heavy hydrocarbons, and so the manufactured fuel gases needed to be purified before they could be used.

Blackburn Meadows is an area of land just inside the Sheffield city border at Tinsley, England. It became the location of the main sewage treatment works for the city in 1884, and is now one of the largest treatment works in Britain. The treatment process was rudimentary, with sludge being removed to ponds and then to drying beds, after which it was used as manure or transferred by rail to a tip at Kilnhurst. The works progressively expanded to improve the quality of effluent discharged to the River Don and was a pioneer in the use of bio-aeration, following experiments by the works manager during the First World War. This process became known as the "Sheffield System", and was demonstrated to visitors from Great Britain and abroad. Despite these improvements, ammonia levels in the river below the works were high, and fish populations did not survive.

The Troy Gas Light Company was a gas lighting company in Troy, New York, United States. The Troy Gasholder Building is one of only ten or so remaining examples of a type of building that was common in Northeastern urban areas during the 19th century. It was designed by Frederick A. Sabbaton, a prominent gas engineer in New York State. Originally sheltering a telescoping iron storage tank for coal gas, the brick gasholder house is an imposing structure from a significant period in the history of Troy. For twenty-seven years the company held a monopoly on the manufacture of illuminating gas in the city.

Derwenthaugh Coke Works was a coking plant on the River Derwent near Swalwell in Gateshead. The works were built in 1928 on the site of the Crowley's Iron Works, which had at one time been the largest iron works in Europe. The coke works was closed and demolished in the late 1980s, and replaced by Derwenthaugh Park.

The former Saratoga Gas, Electric Light and Power Company Complex is located near the northern boundary of Saratoga Springs, New York, United States. It is a seven-acre parcel with two brick buildings on it. In the 1880s it became the thriving resort city's first power station.

The Launceston Gasworks is a former industrial site located in the CBD of Launceston, Tasmania. The site was the principal supplier of gas to the City of Launceston before the importation of LPG in the 1970s. The gasworks produced gas by heating coal and siphoning off the gas that it released before refining and storing it on site in a set of 3, steel frame gasometers. The first buildings on site were the horizontal retort buildings built in 1860 from sandstone and local brick. The site was later used by Origin Energy as their Launceston LPG outlet. The site is instantly recognizable by its 1930s, steel braced, vertical retort building with the words "COOK WITH GAS" in the brickwork.

Southall Gas Works is a former gas works site of around 88 acres (36 ha) in Southall, west London, which is currently being redeveloped for mixed-use including 3,750 homes as part of Berkeley Group's The Green Quarter.

The Glen Davis Shale Oil Works was a shale oil extraction plant, in the Capertee Valley, at Glen Davis, New South Wales, Australia, which operated from 1940 until 1952. It was the last oil-shale operation in Australia, until the Stuart Oil Shale Project in the late 1990s. For the period of 1965–1952, it provided one fifth of the shale oil produced in Australia.

Newstead Gasworks is a heritage-listed former gasometer at 70 Longland Street, Teneriffe, City of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. It was built from 1873 to 1887. It is also known as Brisbane Gas Company Gasworks and Newstead Gasworks No.2 gasholder. It was added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 24 June 2005.

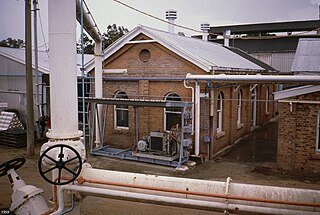

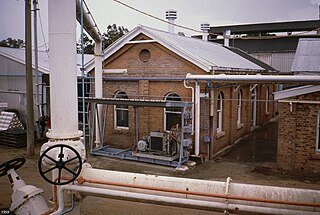

West End Gasworks is a heritage-listed gasworks at 321 Montague Road, West End, Queensland, Australia. It is also known as South Brisbane Gas and Light Company Works. It was added to the Queensland Heritage Register on 22 October 1999.

The Concord Gas Light Company Gasholder House is a historic gasholder house at Gas Street in Concord, New Hampshire. Built in 1888, it is believed to be the only such structure in the United States in which the enclosed gas containment unit is essentially intact. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2018. Since 2012, it has been owned by Liberty Utilities, a gas, water and electric company. In 2022, Liberty struck a deal with the city of Concord and the New Hampshire Preservation Alliance to begin emergency stabilization work on the building, so that planning for protection and future use can continue.