Clovis points are the characteristically fluted projectile points associated with the New World Clovis culture, a prehistoric Paleo-American culture. They are present in dense concentrations across much of North America and they are largely restricted to the north of South America. There are slight differences in points found in the Eastern United States bringing them to sometimes be called "Clovis-like". Clovis points date to the Early Paleoindian period, with all known points dating from roughly 13,400–12,700 years ago. As an example, Clovis remains at the Murry Springs Site date to around 12,900 calendar years ago. Clovis fluted points are named after the city of Clovis, New Mexico, where examples were first found in 1929 by Ridgely Whiteman.

The Folsom tradition is a Paleo-Indian archaeological culture that occupied much of central North America from c. 10800 BCE to c. 10200 BCE. The term was first used in 1927 by Jesse Dade Figgins, director of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. The discovery by archaeologists of projectile points in association with the bones of extinct Bison antiquus, especially at the Folsom site near Folsom, New Mexico, established much greater antiquity for human residence in the Americas than the previous scholarly opinion that humans in the Americas dated back only 3,000 years. The findings at the Folsom site have been called the "discovery that changed American archaeology."

The Plano cultures is a name given by archaeologists to a group of disparate hunter-gatherer communities that occupied the Great Plains area of North America during the Paleo-Indian or Archaic period.

Prehistory of Colorado provides an overview of the activities that occurred prior to Colorado's recorded history. Colorado experienced cataclysmic geological events over billions of years, which shaped the land and resulted in diverse ecosystems. The ecosystems included several ice ages, tropical oceans, and a massive volcanic eruption. Then, ancient layers of earth rose to become the Rocky Mountains.

The Olsen–Chubbuck Bison kill site is a Paleo-Indian site that dates to an estimated 8000–6500 B.C. and provides evidence for bison hunting and using a game drive system, long before the use of the bow and arrow or horses. The site holds a bone bed of nearly 200 bison that were killed, butchered, and consumed by Paleo-Indian hunters. The site is located 16 miles southeast of Kit Carson, Colorado. The site was named after archaeologists, Sigurd Olsen and Gerald Chubbuck, who discovered the bone bed in 1957. In 1958, the excavation of the Olsen-Chubbuck site was then turned over to the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History, a team led by Joe Ben Wheat, an anthropologist employed by the museum.

Franktown Cave is located 25 miles (40 km) south of Denver, Colorado on the north edge of the Palmer Divide. It is the largest rock shelter documented on the Palmer Divide, which contains artifacts from many prehistoric cultures. Prehistoric hunter-gatherers occupied Franktown Cave intermittently for 8,000 years beginning about 6400 BC The site held remarkable lithic and ceramic artifacts, but it is better known for its perishable artifacts, including animal hides, wood, fiber and corn. Material goods were produced for their comfort, task-simplification and religious celebration. There is evidence of the site being a campsite or dwelling as recently as AD 1725.

The Jones-Miller Bison Kill Site, located in northeast Colorado, was a Paleo-Indian site where Bison antiquus were killed using a game drive system and butchered. Hell Gap complex bones and tools artifacts at the site are carbon dated from about ca. 8000-8050 BC.

Lamb Spring is a pre-Clovis prehistoric Paleo-Indian archaeological site located in Douglas County, Colorado with the largest collection of Columbian mammoth bones in the state. Lamb Spring also provides evidence of Paleo-Indian hunting in a later period by the Cody culture complex group. Lamb Spring was listed in 1997 on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Basketmaker culture of the pre-Ancestral Puebloans began about 1500 BC and continued until about AD 750 with the beginning of the Pueblo I Era. The prehistoric American southwestern culture was named "Basketmaker" for the large number of baskets found at archaeological sites of 3,000 to 2,000 years ago.

The Archaic–Early Basketmaker Era was an Archaic cultural period of ancestors to the Ancient Pueblo People. They were distinguished from other Archaic people of the Southwest by their basketry which was used to gather and store food. They became reliant on wild seeds, grasses, nuts, and fruit for food and changed their movement patterns and lifestyle by maximizing the edible wild food and small game within a geographical region. Manos and metates began to be used to process seeds and nuts. With the extinction of megafauna, hunters adapted their tools, using spears with smaller projectile points and then atlatl and darts. Simple dwellings made of wood, brush and earth provided shelter.

Cedar Point Village is an archaeological site located in Elbert County, Colorado near Limon. It is a prehistoric residential site with artifacts of the Dismal River culture and likely inhabited by early Apachean people.

The Dismal River culture refers to a set of cultural attributes first seen in the Dismal River area of Nebraska in the 1930s by archaeologists William Duncan Strong, Waldo Rudolph Wedel and A. T. Hill. Also known as Dismal River aspect and Dismal River complex, dated between 1650 and 1750 A.D., is different from other prehistoric Central Plains and Woodland traditions of the western Plains. The Dismal River people are believed to have spoken an Athabascan language and to have been part of the people later known to Europeans as the Apache.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the prehistoric people of Colorado, which covers the period of when Native Americans lived in Colorado prior to contact with the Domínguez–Escalante expedition in 1776. People's lifestyles included nomadic hunter-gathering, semi-permanent village dwelling, and residing in pueblos.

The Apishapa culture, or Apishapa Phase, a prehistoric culture from 1000 to 1400, was named based upon an archaeological site in the Lower Apishapa canyon in Colorado. The Apishapa River, a tributary of the Arkansas River, formed the Apishapa canyon. In 1976, there were 68 Apishapa sites on the Chaquaqua Plateau in southeastern Colorado.

The Hell Gap complex is a Plano culture from 10,060 to 9,600 before present. It is named after the Hell Gap archaeological site, in Goshen County, Wyoming.

The Sopris phase is a Late Ceramic period hunter-gatherer culture of the Upper Purgatoire, also known as the Upper Purgatoire complex. It was first discovered in the southern Colorado, near the present town of Trinidad, Colorado. The Sopris phase appeared to be greatly influenced by Puebloan people, such as the Taos Pueblo and Pecos Pueblo, and through trade in the Upper Rio Grande area.

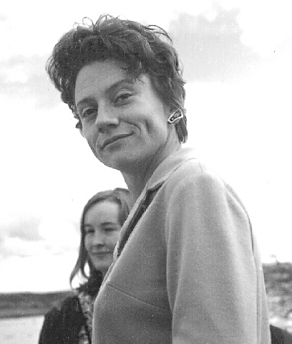

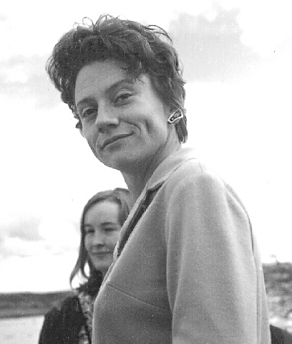

Cynthia Irwin-Williams was an archaeologist of the prehistoric American Southwest. She received a B.A. in Anthropology from Radcliffe College in 1957; the next year she received a M.A. in the same field. In 1963 she completed her educational career in Anthropology with a PhD. from Harvard University. Beginning her career in the 1950s, Irwin-Williams was considered a groundbreaker for women in archaeology, like her friend and supporter Hannah Marie Wormington.

Prehistoric technology is technology that predates recorded history. History is the study of the past using written records. Anything prior to the first written accounts of history is prehistoric, including earlier technologies. About 2.5 million years before writing was developed, technology began with the earliest hominids who used stone tools, which they first used to hunt food, and later to cook.

The game drive system is a hunting strategy in which game are herded into confined or dangerous places where they can be more easily killed. It can also be used for animal capture as well as for hunting, such as for capturing mustangs. The use of the strategy dates back into prehistory. Once a site is identified or manipulated to be used as a game drive site, it may be repeatedly used over many years. Examples include buffalo jumps and desert kites.