A scuba set, originally just scuba, is any breathing apparatus that is entirely carried by an underwater diver and provides the diver with breathing gas at the ambient pressure. Scuba is an anacronym for self-contained underwater breathing apparatus. Although strictly speaking the scuba set is only the diving equipment that is required for providing breathing gas to the diver, general usage includes the harness or rigging by which it is carried and those accessories which are integral parts of the harness and breathing apparatus assembly, such as a jacket or wing style buoyancy compensator and instruments mounted in a combined housing with the pressure gauge. In the looser sense, scuba set has been used to refer to all the diving equipment used by the scuba diver, though this would more commonly and accurately be termed scuba equipment or scuba gear. Scuba is overwhelmingly the most common underwater breathing system used by recreational divers and is also used in professional diving when it provides advantages, usually of mobility and range, over surface-supplied diving systems and is allowed by the relevant legislation and code of practice.

The timeline of underwater diving technology is a chronological list of notable events in the history of the development of underwater diving equipment. With the partial exception of breath-hold diving, the development of underwater diving capacity, scope, and popularity, has been closely linked to available technology, and the physiological constraints of the underwater environment.

Aqua-Lung was the first open-circuit, self-contained underwater breathing apparatus to achieve worldwide popularity and commercial success. This class of equipment is now commonly referred to as a twin-hose diving regulator, or demand valve. The Aqua-Lung was invented in France during the winter of 1942–1943 by two Frenchmen: engineer Émile Gagnan and Jacques Cousteau, who was a Naval Lieutenant. It allowed Cousteau and Gagnan to film and explore underwater more easily.

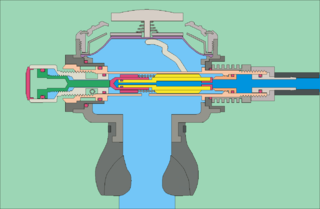

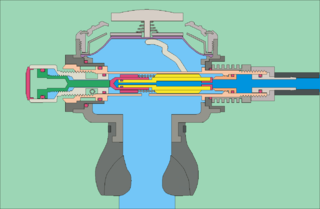

A diving regulator or underwater diving regulator is a pressure regulator that controls the pressure of breathing gas for underwater diving. The most commonly recognised application is to reduce pressurized breathing gas to ambient pressure and deliver it to the diver, but there are also other types of gas pressure regulator used for diving applications. The gas may be air or one of a variety of specially blended breathing gases. The gas may be supplied from a scuba cylinder carried by the diver, in which case it is called a scuba regulator, or via a hose from a compressor or high-pressure storage cylinders at the surface in surface-supplied diving. A gas pressure regulator has one or more valves in series which reduce pressure from the source, and use the downstream pressure as feedback to control the delivered pressure, or the upstream pressure as feedback to prevent excessive flow rates, lowering the pressure at each stage.

Scuba diving is a mode of underwater diving whereby divers use breathing equipment that is completely independent of a surface breathing gas supply, and therefore has a limited but variable endurance. The word scuba is an acronym for "Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus" and was coined by Christian J. Lambertsen in a patent submitted in 1952. Scuba divers carry their own source of breathing gas, usually compressed air, affording them greater independence and movement than surface-supplied divers, and more time underwater than freedivers. Although the use of compressed air is common, other gas blends are also used.

Submarine Products Ltd (1959−1990) was a diving gear manufacturer, with a factory in Hexham in Northumberland, England. It was founded in 1959 by Lieutenant-Commander Hugh Oswell.

Porpoise is a tradename for scuba developed by Ted Eldred in Australia and made there from the late 1940s onwards. The first Porpoise was a closed circuit oxygen rebreather, and the following models were all single hose open circuit regulators.

Vintage scuba is scuba equipment dating from 1975 and earlier, and the practice of diving using such equipment.

Aqualung Group is a manufacturer of self-contained breathing apparatus and other diving equipment. It produced the Aqua-Lung line of regulators, including the CG45 (1945) and the Mistral (1955). From its founding in 1946 until 2016, the company was a division of Air Liquide. The company was sold to Montagu Private Equity in 2016, and subsequently acquired by Barings LLC in 2023.

The Lambertsen Amphibious Respiratory Unit (LARU) is an early model of closed circuit oxygen rebreather used by military frogmen. Christian J. Lambertsen designed a series of them in the US in 1940 and in 1944.

Scuba gas management is the aspect of scuba diving which includes the gas planning, blending, filling, analysing, marking, storage, and transportation of gas cylinders for a dive, the monitoring and switching of breathing gases during a dive, efficient and correct use of the gas, and the provision of emergency gas to another member of the dive team. The primary aim is to ensure that everyone has enough to breathe of a gas suitable for the current depth at all times, and is aware of the gas mixture in use and its effect on decompression obligations, nitrogen narcosis, and oxygen toxicity risk. Some of these functions may be delegated to others, such as the filling of cylinders, or transportation to the dive site, but others are the direct responsibility of the diver using the gas.

Scuba skills are skills required to dive safely using self-contained underwater breathing apparatus, known as a scuba set. Most of these skills are relevant to both open-circuit scuba and rebreather scuba, and many also apply to surface-supplied diving. Some scuba skills, which are critical to divers' safety, may require more practice than standard recreational training provides to achieve reliable competence.

The history of underwater diving starts with freediving as a widespread means of hunting and gathering, both for food and other valuable resources such as pearls and coral. By classical Greek and Roman times commercial applications such as sponge diving and marine salvage were established. Military diving also has a long history, going back at least as far as the Peloponnesian War, with recreational and sporting applications being a recent development. Technological development in ambient pressure diving started with stone weights (skandalopetra) for fast descent. In the 16th and 17th centuries diving bells became functionally useful when a renewable supply of air could be provided to the diver at depth, and progressed to surface-supplied diving helmets—in effect miniature diving bells covering the diver's head and supplied with compressed air by manually operated pumps—which were improved by attaching a waterproof suit to the helmet and in the early 19th century became the standard diving dress.

The history of scuba diving is closely linked with the history of the equipment. By the turn of the twentieth century, two basic architectures for underwater breathing apparatus had been pioneered; open-circuit surface supplied equipment where the diver's exhaled gas is vented directly into the water, and closed-circuit breathing apparatus where the diver's carbon dioxide is filtered from the exhaled breathing gas, which is then recirculated, and more gas added to replenish the oxygen content. Closed circuit equipment was more easily adapted to scuba in the absence of reliable, portable, and economical high pressure gas storage vessels. By the mid-twentieth century, high pressure cylinders were available and two systems for scuba had emerged: open-circuit scuba where the diver's exhaled breath is vented directly into the water, and closed-circuit scuba where the carbon dioxide is removed from the diver's exhaled breath which has oxygen added and is recirculated. Oxygen rebreathers are severely depth limited due to oxygen toxicity risk, which increases with depth, and the available systems for mixed gas rebreathers were fairly bulky and designed for use with diving helmets. The first commercially practical scuba rebreather was designed and built by the diving engineer Henry Fleuss in 1878, while working for Siebe Gorman in London. His self contained breathing apparatus consisted of a rubber mask connected to a breathing bag, with an estimated 50–60% oxygen supplied from a copper tank and carbon dioxide scrubbed by passing it through a bundle of rope yarn soaked in a solution of caustic potash. During the 1930s and all through World War II, the British, Italians and Germans developed and extensively used oxygen rebreathers to equip the first frogmen. In the U.S. Major Christian J. Lambertsen invented a free-swimming oxygen rebreather. In 1952 he patented a modification of his apparatus, this time named SCUBA, an acronym for "self-contained underwater breathing apparatus," which became the generic English word for autonomous breathing equipment for diving, and later for the activity using the equipment. After World War II, military frogmen continued to use rebreathers since they do not make bubbles which would give away the presence of the divers. The high percentage of oxygen used by these early rebreather systems limited the depth at which they could be used due to the risk of convulsions caused by acute oxygen toxicity.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to underwater diving:

The mechanism of diving regulators is the arrangement of components and function of gas pressure regulators used in the systems which supply breathing gases for underwater diving. Both free-flow and demand regulators use mechanical feedback of the downstream pressure to control the opening of a valve which controls gas flow from the upstream, high-pressure side, to the downstream, low-pressure side of each stage. Flow capacity must be sufficient to allow the downstream pressure to be maintained at maximum demand, and sensitivity must be appropriate to deliver maximum required flow rate with a small variation in downstream pressure, and for a large variation in supply pressure, without instability of flow. Open circuit scuba regulators must also deliver against a variable ambient pressure. They must be robust and reliable, as they are life-support equipment which must function in the relatively hostile seawater environment, and the human interface must be comfortable over periods of several hours.