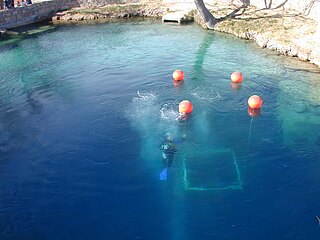

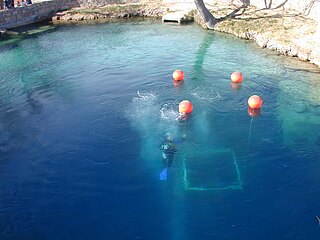

Wreck diving is recreational diving where the wreckage of ships, aircraft and other artificial structures are explored. The term is used mainly by recreational and technical divers. Professional divers, when diving on a shipwreck, generally refer to the specific task, such as salvage work, accident investigation or archaeological survey. Although most wreck dive sites are at shipwrecks, there is an increasing trend to scuttle retired ships to create artificial reef sites. Diving to crashed aircraft can also be considered wreck diving. The recreation of wreck diving makes no distinction as to how the vessel ended up on the bottom.

Cave-diving is underwater diving in water-filled caves. It may be done as an extreme sport, a way of exploring flooded caves for scientific investigation, or for the search for and recovery of divers or, as in the 2018 Thai cave rescue, other cave users. The equipment used varies depending on the circumstances, and ranges from breath hold to surface supplied, but almost all cave-diving is done using scuba equipment, often in specialised configurations with redundancies such as sidemount or backmounted twinset. Recreational cave-diving is generally considered to be a type of technical diving due to the lack of a free surface during large parts of the dive, and often involves planned decompression stops. A distinction is made by recreational diver training agencies between cave-diving and cavern-diving, where cavern diving is deemed to be diving in those parts of a cave where the exit to open water can be seen by natural light. An arbitrary distance limit to the open water surface may also be specified.

Sheck Exley was an American cave diver. He is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of cave diving, and he wrote two major books on the subject: Basic Cave Diving: A Blueprint for Survival and Caverns Measureless to Man. On February 6, 1974, Exley became the first chairman of the Cave Diving Section of the American National Speleological Society. During his career, he established many of the basic safety procedures used in cave and overhead diving today. Exley was also a pioneer of extreme deep scuba diving.

A cenote is a natural pit, or sinkhole, resulting when a collapse of limestone bedrock exposes groundwater. The term originated on the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, where the ancient Maya commonly used cenotes for water supplies, and occasionally for sacrificial offerings. The name derives from a word used by the lowland Yucatec Maya—tsʼonoʼot—to refer to any location with accessible groundwater.

The Cave Diving Group (CDG) is a United Kingdom-based diver training organisation specialising in cave diving.

Piccaninnie Ponds Conservation Park, formerly the Piccaninnie Ponds National Park, is a protected area of 862 hectares located in southeastern South Australia near Mount Gambier.

Ewens Ponds is a series of three water-filled limestone sinkholes in the state of South Australia located in the gazetted locality of Eight Mile Creek, on the watercourse of Eight Mile Creek about 25 kilometres south of Mount Gambier and 8.4 kilometres east of Port MacDonnell. The ponds are popular with recreational divers due to their excellent underwater visibility. It has a small fish population including the endangered golden pygmy perch. Ewens Ponds has been part of the Ewens Ponds Conservation Park since 1976.

Tom Mount was an American pioneering cave diver and technical diver.

The Blue Hole of Santa Rosa, or simply the Blue Hole, is a circular, bell-shaped pool or small lake located along Route 66 east of Santa Rosa, New Mexico that is a tourist attraction and swimming venue, and one of the most popular dive destinations in the US for scuba diving and training. The Blue Hole is an artesian well and cenote that was once used as a fish hatchery.

Agnes Milowka was an Australian technical diver, underwater photographer, author, maritime archaeologist and cave explorer. She gained international recognition for penetrating deeper than previous explorers into cave systems across Australia and Florida, and as a public speaker and author on the subjects of diving and maritime archaeology. She died aged 29 while diving in a confined space.

David Godwin Burchell BEM was a South Australian business man, a recreational scuba diver and a football administrator.

Little Blue Lake is a water-filled sinkhole (“cenote”) in the Australian state of South Australia located in the state's south-east in the locality of Mount Schank about 20 kilometres (12 mi) south of the municipal seat of Mount Gambier. It is notable locally as a swimming hole and nationally as a cave diving site. It is managed by the District Council of Grant and has been developed as a recreational and tourism venue.

Fossil Cave (5L81), formerly known as The Green Waterhole, is a cave in the Limestone Coast region of south-eastern South Australia. It is located in the gazetted locality of Tantanoola about 22 kilometres north-west of the city of Mount Gambier, only a few metres from the Princes Highway between Mount Gambier and Millicent. It is popular with cave divers and is notable for being both a unique paleontological site and the "type locality" for very rare crustaceans which to date have been found only in caves and Blue Lake in the Mount Gambier region.

Engelbrecht Cave is a cave system in the Australian state of South Australia consisting of a sinkhole with two major passages located under the Mount Gambier urban area. It is owned by the local government area of City of Mount Gambier and has been developed as a tourism venue. Its dry extent is notable as a show cave while its water-filled extent is notable as two separate cave diving sites.

Recreational dive sites are specific places that recreational scuba divers go to enjoy the underwater environment or for training purposes. They include technical diving sites beyond the range generally accepted for recreational diving. In this context all diving done for recreational purposes is included. Professional diving tends to be done where the job is, and with the exception of diver training and leading groups of recreational divers, does not generally occur at specific sites chosen for their easy access, pleasant conditions or interesting features.

Scuba diving tourism is the industry based on servicing the requirements of recreational divers at destinations other than where they live. It includes aspects of training, equipment sales, rental and service, guided experiences and environmental tourism.

The Kilsby sinkhole is a sinkhole located near Mount Gambier in South Australia. Since the late 1960s, the naturally occurring karst sinkhole has been used for recreational diving as well as civilian and police diver training. By visiting the Kilsby Sinkhole website, public can now access the site via a pre booked Sinkhole Tour or Snorkelling Tour.

The 1973 Mount Gambier cave diving accident was a scuba diving incident on 28 May 1973 at a flooded sinkhole known as "The Shaft" near Mount Gambier in South Australia. The incident claimed the lives of four recreational scuba divers: siblings Stephen and Christine M. Millott, Gordon G. Roberts, and John H. Bockerman. The four divers explored beyond their own planned limits, without the use of a guideline, and subsequently became lost, eventually exhausting their breathing air and drowning, with their bodies all recovered over the next year. To date, they are the only known fatalities at the site. Four other divers from the same group survived.

Cave diving is underwater diving in water-filled caves. The equipment used varies depending on the circumstances, and ranges from breath hold to surface supplied, but almost all cave diving is done using scuba equipment, often in specialised configurations with redundancies such as sidemount or backmounted twinset. Recreational cave diving is generally considered to be a type of technical diving due to the lack of a free surface during large parts of the dive, and often involves planned decompression stops. A distinction is made by recreational diver training agencies between cave diving and cavern diving, where cavern diving is deemed to be diving in those parts of a cave where the exit to open water can be seen by natural light. An arbitrary distance limit to the open water surface may also be specified. Despite the risks, water-filled caves attract scuba divers, cavers, and speleologists due to their often unexplored nature, and present divers with a technical diving challenge.