Industrial era

Start of modern diving

- 1772: the first diving dress using a compressed-air reservoir was successfully designed and built in 1772 by Sieur [16] Fréminet, a Frenchman from Paris. Fréminet conceived an autonomous breathing machine equipped with a helmet, two hoses for inhalation and exhalation, a suit and a reservoir, dragged by and behind the diver, [17] although Fréminet later put it on his back. [18] : 46 Fréminet called his invention machine hydrostatergatique and used it successfully for more than ten years in the harbours of Le Havre and Brest, as stated in the explanatory text of a 1784 painting. [19] [20]

- 1774: John Day became the first person known to have died in an underwater accident while testing a "diving chamber" in Plymouth Sound. [21] [22]

- 1776: David Bushnell invented the Turtle, first submarine to attack another ship. It was used in the American Revolution. [23]

- 1797: Karl Heinrich Klingert designed a full diving dress which consisted of a large metal helmet and similarly large metal belt connected by a leather jacket and pants. [24]

- 1798: in June, F. W. Joachim, employed by Klingert, successfully completed the first practical tests of Klingert's armor. [25]

- 1800: Captain Peter Kreeft of Germany dived several times with his helmet diving equipment to show it to King Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden. [26]

- 1800: Robert Fulton built a submarine, the "Nautilus". [27]

- 1825: Johan Patrik Ljungström demonstrated his diving bell built of tinned copper with space for a crew of 2-3 persons, equipped with compass and methods of communication to the surface, successfully diving down to about 16 meters with Ljungström and an assistant on board, and wrote a book on the organization of private underwater diving [28] [29]

- c. 1831: American Charles Condert built an autonomous diving suit, using a copper pipe curved in the form of a horseshoe, displacing about 50 pounds of water, and worn at the waist, as an air reservoir which fed compressed air through a manually operated valve and a hose into an airtight rubberised hip length tunic with integral hood. Air escaped from a small hole in the hood. The buoyancy of the set required about 200 pounds of weight for ballast. Condert made several dives in the East River to about 20 ft, and was drowned on his last dive in 1832. [30]

- 1837: Captain William H. Taylor demonstrated his "submarine dress" at the annual American Institute Fair at Niblo's Garden, New York City. [31]

- 1839:

- Canadian inventors James Eliot and Alexander McAvity of Saint John, New Brunswick patented an "oxygen reservoir for divers", a device carried on the diver's back containing "a quantity of condensed oxygen gas or common atmospheric air proportionate to the depth of water and adequate to the time he is intended to remain below". [32]

- W.H.Thornthwaite of Hoxton in London patented an inflatable lifting jacket for divers. [33]

- Around 1842: The Frenchman Joseph-Martin Cabirol (1799–1874) formed a company in Paris and started making standard diving dress. [34]

- 1843: Based on lessons learned from the Royal George salvage, the first diving school was set up by the Royal Navy. [35]

- 1845 James Buchanan Eads designed and built a diving bell and began salvaging cargo from the bottom of the Mississippi River, eventually working on the river bottom from the mouth of the river at the Gulf of Mexico to Iowa. [36]

- 1856: Wilhelm Bauer started the first of 133 successful dives with his second submarine Seeteufel . The crew of 12 was trained to leave the submerged ship through a diving chamber (airlock). [37]

- 1860: Giovanni Luppis, a retired engineer of the Austro-Hungarian navy, demonstrated a design for a self-propelled torpedo to emperor Franz Joseph. [38]

- 1864: H.L. Hunley became the first submarine to sink a ship, the USS Housatonic, during the American Civil War. [39]

- 1866: Minenschiff, the first self-propelled torpedo, developed by Robert Whitehead (to a design by Captain Luppis, Austrian Navy), was demonstrated for the imperial naval commission on 21 December. [40]

- 1882: Brothers Alphonse and Théodore Carmagnolle of Marseille, France, patented the first properly anthropomorphic design of ADS (atmospheric diving suit). Featuring 22 rolling convolute joints that were never entirely waterproof and a helmet with 25 2-inch (51 mm) glass viewing ports, [41] it weighed 380 kilograms (840 lb) and was never put in service. [42]

Rebreathers

- 1808: on 17 June, Sieur Pierre-Marie Touboulic from Brest, a mechanic in Napoleon's Imperial Navy, patented the oldest known oxygen rebreather, but there is no evidence of any prototype having been manufactured. This early rebreather design worked with an oxygen reservoir, the oxygen being delivered progressively by the diver himself and circulating in a closed circuit through a sponge soaked in limewater. [43] Touboulic called his invention Ichtioandre (Greek for 'fish-man'). [44]

- 1849: Pierre-Aimable de Saint Simon Sicard (a chemist) made the first practical oxygen rebreather. It was demonstrated in London in 1854. [33]

- 1853: Professor T. Schwann designed a rebreather in Belgium which he exhibited in Paris in 1878. [45] It had a big backpack tank containing oxygen at about 13 bar, and two scrubbers containing sponges soaked in caustic soda.

- 1876: An English merchant seaman, Henry Fleuss, developed the first workable self-contained diving rig that used compressed oxygen. This prototype of closed-circuit scuba used rope soaked in caustic potash to absorb carbon dioxide so the exhaled gas could be re-breathed. [46]

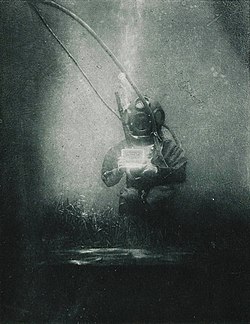

Diving helmets improved and in common use

- 1808: Brizé-Fradin designed a small bell-like helmet connected to a low-pressure backpack air container. [33]

- 1820: Paul Lemaire d'Augerville (a Parisian dentist) invented a diving apparatus with a copper backpack cylinder, a counterlung to save air, and with an inflatable life jacket connected. It was used down to 15 or 20 meters for up to an hour in salvage work. He started a successful salvage company. [33]

- 1825: William H. James designed a self-contained diving suit with compressed air stored in an iron container worn around the waist. [47]

- 1827: Beaudouin in France developed a diving helmet fed from an air cylinder pressurized to 80 to 100 bar. The French Navy was interested, but nothing came of this. [33]

- 1829: (1828?)

- Charles Anthony Deane and John Deane of Whitstable in Kent in England designed the first diving helmet supplied with airpumped from the surface, for use with a diving suit. It is said [ by whom? ]that the idea started from a crude emergency rig-up of a fireman's water-pump (used as an air pump) and a knight-in-armour helmet used to try to rescue horses from a burning stable. Others say that it was based on earlier work in 1823 developing a "smoke helmet". [48] The suit was not attached to the helmet, so a diver could not bend over or invert without risk of flooding the helmet and drowning. Nevertheless, the diving system was used in salvage work, including the successful removal of cannon from the British warship HMS Royal George in 1834–35. This 108-gun fighting ship sank in 65 feet of water at Spithead anchorage in 1783. [48] [47]

- E.K.Gauzen, a Russian naval technician of the Kronshtadt naval base in Saint Petersburg, built a "diving machine". His invention was a metallic helmet strapped to a leather suit (an overall) with a pumped air supply. The bottom of the helmet was open, and the helmet strapped to the suit by a metal band. Gauzen's diving suit and its further modifications were used by the Russian Navy until 1880. The modified diving suit of the Russian Navy, based on Gauzen's invention, was known as "three-bolt equipment". [47]

- 1837: Following up Leonardo da Vinci's studies, and those of the astronomer Edmond Halley, Augustus Siebe developed surface-supplied diving apparatus which became known as standard diving dress. [49] By sealing the Deane brothers' helmet design to a waterproof suit, Augustus Siebe developed the Siebe "Closed" Dress combination diving helmet and suit, considered the foundation of modern diving dress. This was a significant evolution from previous models of "open" dress that did not allow a diver to invert. Siebe-Gorman went on to manufacture helmets continuously until 1975. [48]

- 1840: The Royal Navy used Siebe closed dress for salvage and blasting work on the "Royal George", and subsequently the Royal Engineers standardised on this equipment. [48]

- 1843: The Royal Navy established the first diving school. [48]

- 1855: Joseph-Martin Cabirol patented a new model of standard diving dress, mainly issued from Siebe's designs. The suit was made out of rubberized canvas and the helmet, for the first time, included a hand-controlled tap that the diver used to evacuate his exhaled air. The exhaust valve included a non-return valve which prevented water from entering in the helmet. Until 1855 diving helmets were equipped with only three circular windows (for front, left and right sides). Cabirol's helmet introduced the later well known fourth window, situated in the upper front part of the helmet and allowing the diver to see above him. Cabirol's diving dress won the silver medal at the 1885 Exposition Universelle in Paris. This original diving dress and helmet are now preserved at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers in Paris. [50]

The first diving regulators

- 1838: Dr. Manuel Théodore Guillaumet invented a twin-hose demand regulator. On 19 June 1838, in London, England, a Mr. William Edward Newton filed a patent (no. 7695: "Diving apparatus") for a diaphragm-actuated, twin-hose demand valve for divers. [51] However, it is believed that Mr. Newton was merely filing a patent on behalf of Dr. Guillaumet. The illustration of the apparatus in Newton's patent application is identical to that in Guillaumet's patent application; furthermore, Mr. Newton was apparently an employee of the British Office for Patents, who applied for patents on behalf of foreign applicants. [52] It is demonstrated in surface-demand use. During the demonstration, use duration was limited to 30 minutes because the dive was in cold water without a diving suit. [53] [54] [18] : 45

- 1860: in Espalion (France), mining engineer Benoît Rouquayrol designed a self-contained breathing set with a backpack cylindrical air tank that supplied air through the first demand regulator to be commercialized (as of 1865, see below). Rouquayrol calls his invention régulateur ('regulator'), having conceived it to help miners avoid drowning in flooded mines. [55]

- 1864: Benoît Rouquayrol met navy officer Auguste Denayrouze for the first time, in Espalion, and on Denayrouze's initiative, they adapted Rouquayrol's invention to diving. After having adapted it, they called their recently patented device appareil plongeur Rouquayrol-Denayrouze ('Rouquayrol-Denayrouze diving apparatus'). The diver still walked on the seabed and did not swim. The air pressure tanks made with the technology of the time could only hold 30 atmospheres, allowing dives of only 30 minutes at no more than ten meters deep; [56] during surface-supplied configuration the tank was also used for bailout in the case of a hose failure. [56]

- 1865: on August the 28th the French Navy Minister ordered the first Rouquayrol-Denayrouze diving apparatus and large scale production started. [43]

Gas and air cylinders appear

- Late 19th century: Industry began to be able to make high-pressure air and gas cylinders. That prompted a few inventors down the years to design open-circuit compressed air breathing sets, but they were all constant-flow, and the demand regulator did not come back until 1937. [47]

Underwater photography

- 1856: William Thompson Archived 12 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine and his friend Mr Kenyon take the first under water photograph using a camera sealed in a metal box. [57] [58]

- 1893: Louis Boutan makes the first under water camera becoming the first underwater photographer and produces the first clear underwater photographs. [59] [60]

- 1900: Louis Boutan published La Photographie sous-marine et les progrès de la photographie (The Underwater Photography and the Advances in Photography), the first book about underwater photography. [60]

Decompression sickness recognised as a problem

- 1841: Jacques Triger constructs the first caisson for mining work in France. First two cases of decompression sickness in caisson workers are reported by Triger in 1845, consisting of joint and extremity pains. [13]

- 1846-1855: Several cases of decompression sickness, some with fatal outcome, reported in caisson workers during bridge construction first in France, then in England. Recompression is reported to help alleviate symptoms by Pol and Wattelle in 1847, and a gradual compression and decompression is advocated by Thomas Littleton in 1855. [13] [61]

- From 1870 to 1910 all prominent features of decompression sickness were established, but theories over the pathology ranged from cold or exhaustion causing reflex spinal cord damage; electricity caused by friction on compression; or organ congestion and vascular stasis caused by decompression. [13]

- 1870: Louis Bauer, a professor of surgery from St. Lous, publishes an initial report on the outcomes of 25 paralyzed caisson workers involved in the construction of the St Louis Eads Bridge. [62] The construction project eventually employed 352 compressed air workers including Dr. Alphonse Jaminet as the physician in charge. There were 30 seriously injured and 12 fatalities. Dr. Jaminet himself suffered a case of decompression sickness when he ascended to the surface in four minutes after spending almost three hours at a depth of 95 feet in a caisson, and his description of his own experience was the first such recorded. [63] While obviously caused by the increased pressure, both Bauer and Jaminet theorized that the symptoms were caused by a hypermetabolic state caused by the increase in oxygen, with inability to remove waste products in normal pressure. Gradual compression and decompression, shorter shifts with longer intervals, and complete rest after decompression were advocated. Actual cases were treated with rest, beef tea, ice, and alcohol. [64]

- 1872: The similarity between decompression sickness and iatrogenic air embolism as well as the relationship between inadequate decompression and decompression sickness were noted by Hermann Friedberg. [65] [66] He suggested that intravascular gas was released by rapid decompression and recommended: slow compression and decompression; four-hour working shifts; limit to maximum depth 44.1 psig (4 ATA); using only healthy workers; and recompression treatment for severe cases. [13]

- 1873: Dr. Andrew Smith first used the term "caisson disease" to describe 110 cases of decompression sickness as the physician in charge during construction of the Brooklyn Bridge. [63] The project employed 600 compressed air workers. Recompression treatment was not used. The project chief engineer Washington Roebling suffered from caisson disease. (He took charge after his father John Augustus Roebling died of tetanus.) Washington's wife, Emily, helped manage the construction of the bridge after his sickness confined him to his home in Brooklyn. He battled the after-effects of the disease for the rest of his life.

According to different sources, the term "The Bends" for decompression sickness was coined by workers of either the Brooklyn or the Eads bridge, and was given because afflicted individuals characteristically arched their backs in a manner similar to a then-fashionable posture known as the Grecian Bend. [63]

Twentieth century

- 1900: John P. Holland built the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the U.S. Navy, Holland (also called A-1). [68]

- Leonard Hill used a frog model to prove that decompression causes bubbles and that recompression resolves them. [13]

- 1903: Siebe Gorman started to make a submarine escape set in England; in the years afterwards it was improved, and later was called the Davis Escape Set or Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus. [46]

- from 1903 to 1907: Professor Georges Jaubert, invented Oxylithe, a mixture of peroxides of sodium (Na2O2) and potassium with a small amount of salts of copper or nickel, which produces oxygen in the presence of water. [69]

- 1905:

- Several sources, including the 1991 US Navy Dive Manual (pg 1–8), state that the MK V Deep Sea Diving Dress was designed by the Bureau of Construction & Repair in 1905, but in reality, the 1905 Navy Handbook shows British Siebe-Gorman helmets in use. Since the earliest known MK V is dated 1916, these sources are probably referring to the earlier MK I, MK II, MK III & MK IV Morse and Schrader helmets. [48]

- The first rebreather with metering valves to control the supply of oxygen was made. [70]

- 1907: Draeger of Lübeck made a rebreather called the U-Boot-Retter. (submarine rescuer). [71]

- 1908:

- Arthur Boycott, Guybon Damant, and John Haldane published "The Prevention of Compressed-Air Illness", detailed studies on the cause and symptoms of decompression sickness, and proposed a table of decompression stops to avoid the effects. [13] [72]

- The Admiralty Deep Diving Committee adopted the Haldane tables for the Royal Navy, and published Haldane's diving tables to the general public. [13]

- 1910: the British Robert Davis invented his own submarine rescuer rebreather, the Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus, for the Royal Navy submarine crews.[ citation needed ]

- 1912:

- US Navy adopted the decompression tables published by Haldane, Boycott and Damant. Driven by Chief Gunner George Stillson, the navy set up a program to test tables and staged decompression based on the work of Haldane. [73]

- Maurice Fernez introduced a simple lightweight underwater breathing apparatus as an alternative to helmet diving suits. [74]

- Dräger started the commercialization of his rebreather in both configuration types, mouthpiece and helmet. [75]

- 1913: The US Navy began developing the future MK V, influenced by Schrader and Morse designs. [73] [48]

- 1914: Modern swimfins were invented by the Frenchman Louis de Corlieu, capitaine de corvette (Lieutenant Commander) in the French Navy. In 1914 De Corlieu made a practical demonstration of his first prototype for a group of navy officers. [18] : 65

- 1915: The submarine USS F-4 was salvaged from 304 feet establishing the practical limits for air diving. Three US Navy divers, Frank W. Crilley, William F. Loughman, and Nielson, reached 304 fsw using the MK V dress. [48]

- 1916:

- The basic design of the MK V dress was finalized by including a battery-powered telephone, but several more detail improvements were made over the next two years. [48]

- The Draeger model DM 2 became standard equipment of the Imperial German Navy.[ citation needed ]

- 1917: The Bureau of Construction & Repair adopted the MK V helmet and dress, which remained the standard for US Navy diving until the introduction of the MK 12 in the late seventies. [48]

- 1918: the "Ohgushi's Peerless Respirator" was first patented. Invented in 1916 by Riichi Watanabi and the blacksmith Kinzo Ohgushi, and used with either surface-supplied air or a 150 bar steel scuba cylinder holding 1000 litres free air, the valve-supplied air to a mask over the diver's nose and eyes and the demand valve was operated by the diver's teeth. Gas flow was proportional to bite force and duration. The breathing apparatus was used successfully for fishing and salvage work and by the military Japanese Underwater Unit until the end of the Pacific War. [76] [77]

- Around 1920: Hanseatischen Apparatebau-Gesellschaft made a 2-cylinder breathing apparatus with double-lever single-stage demand valve and single wide corrugated breathing tube with mouthpiece, and a "duck's beak" exhalent valve in the regulator. It was described in a mine rescue handbook in 1930. They were successors to Ludwig von Bremen of Kiel, who had the licence to make the Rouquayrol-Denayrouze apparatus in Germany. [78]

- 1924:

- 1925:

- Maurice Fernez introduced a new model of his underwater surface-supplied apparatus at the Grand Palais. Yves le Prieur, an assistant at the exhibition, decided to meet Fernez in person and asked him to transform the equipment into a manually controlled constant-flow self-contained underwater breathing apparatus. [80]

- Due to post World War I cutbacks, the US Navy found it had only 20 divers qualified to dive deeper than 90 feet when salvaging the submarine S-51. [48]

- 1926:

- Fernez-Le Prieur self-contained underwater breathing apparatus was demonstrated to the public in Paris, [81] and adopted by the French Navy.[ citation needed ]

- Dräger introduced a rescue breathing apparatus that the wearer could swim with. Previous devices served only for submarine escape and were designed to provide buoyancy so that the wearer was lifted to the surface without effort, the diving set had weights, which made it possible to dive for search and rescue after an accident.[ citation needed ]

- 1927: US Navy School of Diving and Salvage was re-established at Washington Navy Yard, and the Experimental Diving Unit brought from Pittsburgh to Washington Navy Yard. [48]

- 1928: Davis invented the Submersible Decompression Chamber (SDC) diving bell. [48]

- 1929: Lieutenant C.B."Swede" Momsen, a submariner and diver, developed and tested the submarine escape apparatus named the Momsen Lung. [48]

- The 1930s:

- In France, Guy Gilpatric started swim diving with waterproof goggles, derived from the swimming goggles which were invented by Maurice Fernez in 1920.[ citation needed ]

- Sport spearfishing became common in the Mediterranean, and spearfishers gradually developed the diving mask, fins and snorkel, with Georges Beuchat in Marseille, France, who created the speargun. Italian sport spearfishers started using oxygen rebreathers. This practice came to the attention of the Italian Navy, which developed its frogman unit Decima Flottiglia MAS.[ citation needed ]

- 1933:

- In April Louis de Corlieu registered a new patent (number 767013, which in addition to two fins for the feet included two spoon-shaped fins for the hands) and called this equipment propulseurs de natation et de sauvetage (which can be translated as "swimming and rescue propulsion device"). [18] : 65

- In San Diego, California, the first sport diving club was started by Glenn Orr, Jack Prodanovich and Ben Stone, called the San Diego Bottom Scratchers. [82] As far as it is known, it did not use breathing sets; its main aim was spearfishing.

- More is known of Yves Le Prieur's constant-flow open-circuit breathing set. It is said that it could allow a 20-minute stay at 7 meters and 15 minutes at 15 meters. It has one cylinder feeding into a circular fullface mask. Its air cylinder was often worn at an angle to get its on/off valve in reach of the diver's hand.[ citation needed ]

- 1934:

- In France, Beuchat established a scuba diving and spearfishing equipment manufacturing company. [83]

- In France a sport diving club was started, called the Club des Sous-l'Eau = "club of those [who are] under the water". It did not use breathing sets as far as is known. Its main aim was spearfishing. ("Club des Sous-l'Eau" was later realized to be a homophone of "club des soulôts" = "club of the drunkards", and was changed to Club des Scaphandres et de la Vie Sous L'Eau = "Club of the diving apparatuses and of underwater life".)[ citation needed ]

- Otis Barton and William Beebe dived to 3028 feet using a bathysphere. [84]

- 1935: The French Navy adopted the Le Prieur breathing set. [85]

- On the French Riviera, the first known sport scuba diving club Club Des Scaphandres et de la Vie Sous L'eau (The club for divers and life underwater) was started by Le Prieur & Jean Painleve. It used Le Prieur's breathing sets.[ citation needed ]

- 1937: US Navy published its revised diving tables based on the work of O.D. Yarbrough. [73]

- 1937: The American Diving Equipment and Salvage Company (now known as DESCO) developed a heavy bottom-walking-type diving suit with a self-contained mixed-gas helium and oxygen rebreather.[ citation needed ]

- 1939: After floundering for years, even producing his fins in his own flat in Paris, De Corlieu finally started mass production of his invention in France. The same year he rented a licence to Owen P. Churchill for mass production in the United States. To sell his fins in the USA Owen Churchill changed the French De Corlieu's name (propulseurs) to "swimfins", which is still the English name. Churchill presented his fins to the US Navy, who decided to acquire them for its Underwater Demolition Team (UDT).[ citation needed ]

- Hans Hass and Hermann Stelzner of Dräger, in Germany made the M138 rebreather. It was developed from the 1912 escape set, a type of rebreather used to exit sunken submarines. The M138 sets were oxygen rebreathers with a 150 bar, 0.6 liter tank and appeared in many of his movies and books.[ citation needed ]

- 1941: The Italian Navy's Decima Flottiglia MAS using oxygen rebreathers and manned torpedoes, attacked the British fleet in Alexandria harbor. [86]

- 1944: American UDT and British COPP frogmen (COPP: Combined Operations Pilotage Parties) used the "Churchill fins" during all prior underwater deminings, allowing this way in 1944 the Normandy landings. During years after World War II had ended, De Corlieu spent time and efforts struggling with civil procedures for patent infringement. [18] : 66

The demand regulator reappears

- 1934: René Commeinhes, from Alsace, invented a breathing set working with a demand valve and designed to allow firefighters to breathe safely in smoke-filled environments. [87]

- 1937: Georges Commeinhes, son of René, adapted his father's invention to diving and developed a two-cylinder open-circuit apparatus with demand regulator. The regulator was a big rectangular box between the cylinders. Some were made, but WWII interrupted development.[ citation needed ]

World War II

- 1939: Georges Commeinhes offered his breathing set to the French Navy, which could not continue developing uses for it because of WWII. [88]

- 1940-1944: Christian J. Lambertsen of the United States designed a rebreather 'Breathing apparatus' for the U.S. military. [89]

- 1942: Georges Commeinhes patented a better version of his scuba set, now called the GC42 ("G" for Georges, "C" for Commeinhes and "42" for 1942). Some are made by the Commeinhes' company.[ citation needed ]

- 1942: with no relation with the Commeinhes family, Émile Gagnan, an engineer employed by the Air Liquide company, obtained a Rouquayrol-Denayrouze apparatus (property of the Bernard Piel company in 1942) in Paris. He miniaturized and adapted it to gas generators, since the Germans occupy France and confiscated the French fuel for war purposes. Gagnan's boss and owner of the Air Liquide company, Henri Melchior, decided to introduce Gagnan to Jacques-Yves Cousteau, his son-in-law, because he knows that Cousteau is looking for an efficient and automatic demand regulator. They met in Paris in December 1942 and adapted Gagnan's regulator to a diving cylinder. [90]

- 1943: after fixing some technical problems, Cousteau and Gagnan patented the first modern demand regulator.[ citation needed ]

- Air Liquide built two more aqualungs: these three are owned by Cousteau but also at the disposal of his first two diving companions Frédéric Dumas and Taillez. They use them to shoot the film Épaves (Shipwrecks), the first underwater film shot using scuba sets. [91]

- In July Commeinhes reached 53 metres (about 174 feet) using his GC42 breathing set off the coast of Marseille. [92]

- In October, and not knowing about Commeinhes's exploit, Dumas dived with a Cousteau-Gagnan prototype and reached 62 metres (about 200 feet) off Les Goudes, not far from Marseille. He experienced what is now called nitrogen narcosis. [93]

- 1944: Commeinhes died in the liberation of Strasbourg in Alsace. [94] His invention was overtaken by Cousteau's invention. [95]

- Various nations use frogmen equipped with rebreathers for war actions: see Human torpedo.[ citation needed ]

- Hans Hass later said that during WWII the German diving gear firm Dräger offered him an open-circuit scuba set with a demand regulator. It may have been a separate invention, or it may have been copied from a captured Commeinhes-type set.[ citation needed ]

- Early 1944: the USA government, to try to stop men from being drowned in sunken army tanks, asked the company Mine Safety Appliances (MSA) for a suitable small escape breathing set. MSA provided a small open-circuit breathing set with a small (5 to 7 liters) air cylinder, a circular demand regulator with a two-lever system similar to Cousteau's design (connected to the cylinder by a nut and cone nipple connection), and one corrugated wide breathing tube connected to a mouthpiece. This set was stated to be made from "off-the-shelf" items, which shows that MSA already had that regulator design; also, that regulator looks like the result of development and not a prototype; it may have arisen around 1943. [96] In an example recovered in 2003 from a submerged Sherman tank in the Bay of Naples, the cylinder was bound round in tape and tied to a lifejacket. These sets were too late for the D-Day landings in June 1944, but were used in the invasion of the south of France and in the Pacific War.[ citation needed ]

- 1944: Cousteau's first aqualung was destroyed by a stray artillery shell in an Allied landing on the French Riviera: that leaves two.[ citation needed ]

Postwar

- The public first heard about frogmen. [97] [98]

- 1945: In Toulon, Cousteau showed the film Épaves to the Admiral Lemonnier. The Admiral then made Cousteau responsible for the creation of the underwater research unit of the French Navy (the GRS, Groupe de Recherches Sous-marines, nowadays called the CEPHISMER). [99] GRS' first mission was to clear of mines the French coasts and harbours. While creating the GRS, Cousteau only had at his disposal the two remaining Aqua-Lung prototypes made by l'Air Liquide in 1943. [100]

- 1946:

- Air Liquide created La Spirotechnique and started to sell Cousteau-Gagnan sets under the names of scaphandre Cousteau-Gagnan ('Cousteau-Gagnan scuba set'), CG45 ("C" for Cousteau, "G" for Gagnan and "45" for 1945, year of their first postwar patent) or Aqua-Lung, the latter for commercialization in English-speaking countries. This word is correctly a tradename that goes with the Cousteau-Gagnan patent, but in Britain it has been commonly used as a generic and spelt "aqualung" since at least the 1950s, including in the BSAC's publications and training manuals, and describing scuba diving as "aqualunging".[ citation needed ]

- Henri Broussard founded the first post-WWII scuba diving club, the Club Alpin Sous-Marin. Broussard was one of the first men who Cousteau trained in the GRS. [101]

- Yves Le Prieur invented a new version of his breathing set. Its fullface mask's front plate was loose in its seating and acted as a very big, and therefore, very sensitive diaphragm for a demand regulator: see Diving regulator#Demand valve.[ citation needed ]

- The first known underwater diving club in Britain, "The Amphibians Club", is formed in Aberdeen by Ivor Howitt (who modified an old civilian gas mask) and some friends. They called underwater diving "fathomeering", to distinguish from jumping into water.[ citation needed ]

- The Cave Diving Group (CDG) is formed in Britain. [102]

- 1947: Maurice Fargues became the first diver to die using an aqualung while attempting a new depth record with Cousteau's Undersea Research Group near Toulon. [22]

- 1948:

- Auguste Piccard sent the first bathyscaphe, FNRS-2, on unmanned dives. [103]

- Siebe Gorman and/or Heinke started making Cousteau-type aqualungs in England. Siebe Gorman made those first patented aqualungs at Chessington from 1948 to 1960, popularly known as tadpole sets. [104] Siebe Gorman and the Royal Navy expected aqualungs to be used with weighted boots for bottom-walking for light commercial diving: see Aqua-lung#"Tadpoles".[ citation needed ]

- Ted Eldred in Australia started developing the first open-circuit single-hose scuba set known: see Porpoise (make of scuba gear).[ citation needed ]

- Georges Beuchat in France created the first surface buoy.[ citation needed ]

- 1948 or 1949: Rene's Sporting Goods shop in California imported aqualungs from France. Two graduate students, Andy Rechnitzer and Bob Dill obtained a set and began to use it for underwater research. [105]

- 1949: Otis Barton made a record dive to 4,500 feet in the Benthoscope. [106]

- 1950: a British naval diving manual printed soon after this said that the aqualung is to be used for walking on the bottom with a heavy diving suit and weighted boots, and did not mention Cousteau.[ citation needed ]

- A report to Cousteau said that only 10 aqualung sets had been sent to the USA because the market there was saturated.[ citation needed ]

- The first camera housing called Tarzan is released by Georges Beuchat,[ citation needed ]

- 1951:

- The movie "The Frogmen" was released. It was set in the Pacific Ocean in WWII. In its last 20 minutes, it shows US frogmen, using bulky 3-cylindered aqualungs on a combat mission. This equipment use is anachronistic (in reality they would have used rebreathers), but it shows that aqualungs were available (even if not widely known of) in the US in 1951.[ citation needed ]

- The US Navy started to develop wetsuits, but not known to the public. [73] [107] [108]

- In December 1951 the first issue of Skin Diver Magazine (USA) appeared. The magazine ran until November 2002.[ citation needed ]

- Cousteau-type aqualungs went on sale in Canada.[ citation needed ]

- 1952:

- UC Berkeley and subsequent UC San Diego Scripps Institution of Oceanography physicist Hugh Bradner, invented the modern wetsuit. [109]

- Cousteau-type aqualungs went on sale in the USA.[ citation needed ]

- Ted Eldred in Melbourne, Australia started making for public sale the Porpoise (make of scuba gear). This was the world's first commercially available single-hose scuba unit and was the forerunner of most sport SCUBA equipment produced today. Only about 12,000 were made. [110]

- After World War II Lambertsen called his 1940-1944 rebreather LARU (for Lambertsen Amphibious Respiratory Unit) but as of 1952 Lambertsen renamed his invention and coined the acronym SCUBA (for "self-contained underwater breathing apparatus"). During the following years this acronym was used, more and more, to identify the Cousteau-Gagnan apparatus, taking the place of its original name (Aqualung). In Britain the word aqualung, used for any demand-valve-controlled open-circuit scuba set, still continues to be used.

Public interest in scuba diving takes off

- 1953: National Geographic Magazine published an article about Cousteau's underwater archaeology at Grand Congloué island near Marseille. This started a massive public demand for aqualungs and diving gear, and in France and America the diving gear makers started making them as fast as they could. But in Britain Siebe Gorman and Heinke kept aqualungs expensive, and restrictions on exporting currency stopped people from importing them. Many British sport divers used home-made constant-flow breathing sets and ex-armed forces or ex-industrial rebreathers. In the early 1950s, diving regulators made by Siebe Gorman cost £15, which was an average week's salary.[ citation needed ]

- After the supply of war-surplus frogman's drysuits ran out, free-swimming diving suits were not readily available to the general public, and as a result many scuba divers dived with their skin bare except for swimming trunks. That is why scuba diving used often to be called skindiving. Others dived in homemade drysuits, or in thick layers of ordinary clothes.[ citation needed ]

- After the supply of war-surplus frogman's fins dried up, for a long time fins were not available to the public, and some had to resort to such things as gluing marine ply to plimsolls.[ citation needed ]

- Captain Trevor Hampton founded the British Underwater Centre at Dartmouth in Devon in England. [111]

- False Bay Underwater Club founded in Cape Town, South Africa (1950). [112]

- Rene's Sporting Goods shop (now owned by La Spirotechnique) became U.S. Divers, now a leading maker of diving equipment. [113]

- 15 October 1953: The British Sub-Aqua Club (BSAC) was founded. [114] [115]

- 1954: USS Nautilus, the first nuclear-powered submarine, was launched. [116]

- The first manned dives in the bathyscaphe FNRS-2 were made. [117]

- The first scuba certification course in the USA was offered by the Los Angeles County Department of Parks and Recreation. The training program was created by Albert Tillman and Bev Morgan now known as LA County Scuba. [118]

- In the US, MSA advertised (in Popular Mechanics magazine) a two-cylinder aqualung-like open-circuit diving set using the MSA regulator. [96]

- Underwater hockey (octopush) was invented by four navy sub-aqua divers in Southsea who got bored swimming up and down and wanted a fun way to keep fit. [119]

- 1955: In Britain, " Practical Mechanics " magazine published an article on "Making an Aqualung". [120]

- Jacques-Yves Cousteau and assistant director Louis Malle, a young film maker of 23, shot The Silent World , one of the first films to use underwater cinematography to show the ocean depths in color. [121]

- Fédération Française d'Études et de Sports Sous-Marins (FFESSM) was formed. [122]

- 1956:

- US Navy published decompression tables that allowed for repetitive diving. [123]

- Around this time, some British scuba divers started making homemade diving demand regulators from industrial parts, including Calor Gas regulators. (Since then, Calor Gas regulators have been redesigned, and this conversion is now impossible.)[ citation needed ]

- Later, Submarine Products Ltd in Hexham in Northumberland, England designed round the Cousteau-Gagnan patent and marketed recreational diving breathing sets at an accessible price. This forced Siebe Gorman's and Heinke's prices down and started them selling to the sport diving trade. (Siebe Gorman gave its drysuit the tradename "Frogman".) Because of this better availability of aqualungs, BSAC adopted a policy that rebreathers were unacceptable for recreational diving.[ citation needed ][ original research? ] In the US, some oxygen diving clubs developed down the years. Eventually, the term of the Cousteau-Gagnan patent expired, and it could be legally copied.[ citation needed ]

- The Silent World received an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature, and the Palme d'Or award at the Cannes Film Festival. [124]

- 1958:

- The U.S. television series Sea Hunt began. It introduced scuba diving to the television audience. It ran until 1961. [125]

- USS Nautilus completed the first ever voyage under the polar ice to the North Pole and back. [126]

- The Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques (CMAS) (World Underwater Federation) was founded in Brussels.[ citation needed ]

- August 1959: YMCA SCUBA Program was founded. [127]

- 1960: Jacques Piccard and Lieutenant Don Walsh, USN, descended to the bottom of the Challenger Deep, the deepest known point in the ocean (about 10900 m or 35802 ft, or 6.78 miles) in the bathyscaphe Trieste. [128]

- USS Triton completes the first ever underwater circumnavigation of the world. [129]

- In Italy, sport diving oxygen rebreathers continued to be made well into the 1960s.[ citation needed ]

- 1961 [130]

- The patent for the PA 61 horse-collar buoyancy compensator is filed by Fenzy.

- The Italian made SOS analog decompression meter is released.

- The Mistral regulator is equipped with non-return valves in the breathing hoses.

- 1962:

- Robert Sténuit lives aboard a tiny one-man cylinder at 200 feet for over 24 hours off Villefranche-sur-Mer on the French Riviera, becoming the world's first aquanaut. [22] [131] [132]

- Swiss diver Hannes Keller reaches over 1,000 feet (300 m) depth off California. [48]

- Edward A. Link's Man-in-the-Sea program had one man breathing helium-oxygen at 200 fsw for 24 hours in the first practical saturation dive. [48]

- 1964:

- In France, Georges Beuchat creates the Jetfins, first vented fins.[ citation needed ]

- The U.S. Navy's Sealab 1 underwater habitat project directed by Captain George F. Bond, keeps four divers in saturation underwater at an average depth of 193 feet for 11 days. [48]

- 1965:

- Robert D. Workman of the U.S. Navy Experimental Diving Unit (NEDU) publishes an algorithm for computing decompression requirements suitable for implementing in a dive computer, rather than a pre-computed table. [133]

- Bob Kirby and Bev Morgan formed Kirby-Morgan. [48]

- Three teams of ten men each spent 15 days under saturation at 205 fsw in Sealab II. Astronaut Scott Carpenter stayed for 30 days. [48]

- The action/adventure movie Thunderball , which used both sorts of open-circuit scuba, was released and helped make single-hose regulators popular. [134]

- 1966:

- Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI) was founded by John Cronin and Ralph Erickson. [135]

- Scubapro introduced the decompression meter (the first analog dive computer). [136]

- 1968: An excursion dive to 1025 fsw was made from a saturation depth of 825 fsw at NEDU. [48]

- 1969: The first known rebreather with electronic monitoring was produced. The Electrolung, designed by Walter Starke, was subsequently bought by Beckman Instruments, but discontinued in 1970 after a number of fatalities. [137]

- 1971: Scubapro introduced the Stabilization Jacket, commonly called stab jacket in England, and Buoyancy Control (or Compensation) Device (BC or BCD) elsewhere.[ citation needed ]

- 1976: Professor Albert A. Bühlmann published his work extending the formulae to apply to diving at altitude and with complex gas mixes. [138]

- 1978: Deeper diving techniques breathing Mixed Gas (Helium/Oxygen) rather than Air were becoming more widely used, due to the requirements of Oil and Gas industry clients in the UK North Sea and elsewhere. The first effective Helium recycling systems where breathed out Heliox diving mix was returned to the surface for CO2 scrubbing and O2 injection were deployed by KD Marine and subsequent Krasberg (Alan Krasberg, gas systems engineer) reclaim systems were used by Commercial Diving operators such as Wharton Williams, Stena Offshore, KD Marine etc. Helium recycling was regularly better than 90% efficient and brought the cost of deeper diving techniques down to a reasonable threshold.

- 1981: The "Salvage of the Century" - the recovery of 431 Gold bars from HMS Edinburgh was carried out from the DSV Stephaniturm by Wharton Williams divers from a water depth of around 800 feet. This operation and all subsequent Helium/Oxygen breathing operations by Wharton Williams used Krasberg based Helium recycling. As new diving vessels were constructed Gas Reclaim technology became a standard fitment.

- 1983: The Orca Edge (the first commercially viable electronic dive computer) was introduced. [139] [140]

- 1985:

- The wreck of RMS Titanic was found. Air India Flight 182, a Boeing 747 aircraft, was found and salvaged off Cork, Ireland during the first large scale deep water (6,200 feet) air crash investigation.[ citation needed ]

- International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers (IANTD) was founded [141] [ citation needed ]

- 1986 Apeks Marine Equipment introduced the first dry sealed 1st Stage developed by engineering designer Alan Clarke, later to house a patented electronic pressure sensor named STATUS.[ citation needed ]

- 1989: The film The Abyss (including an as-yet-fictional deep-sea liquid-breathing set) helped to make scuba diving popular.[ citation needed ]

- The Communist Bloc fell apart and the Cold War ended (see Fall of Communism and dissolution of the Soviet Union ), and with it the risk of future attack by Communist Bloc forces including by their combat divers. After that, the world's armed forces had less reason to requisition rebreather patents submitted by civilians, and sport diving automatic and semi-automatic mixture rebreathers start to appear.[ citation needed ]

- 1990: During operations in the Campos basin of Brazil, saturation divers from the DSV Stena Marianos performed a manifold installation for Petrobras at 316 metres (1,037 ft) depth in February 1990. When a lift bag attachment failed, the equipment was carried by the bottom currents to 328 metres (1,076 ft) depth, and the Brazilian diver Adelson D'Araujo Santos Jr. made the recovery and installation. [142]

- 1994:

- Divex and Kirby-Morgan developed the Divex UltraJewel 601 gas-reclaim system in response to rising helium costs. [48]

- Technical Diving International was founded to focus on training beyond the contemporary scope of recreational diving. [143] [144]

- 1995: BSAC allowed nitrox diving and introduced nitrox training. [115] [145]

- 1996: PADI introduced its Enriched Air Diver Course. [146]

- 1997: The film Titanic helped to make underwater trips onboard MIR submersible vehicles popular.[ citation needed ]

- 1998 August: Dives on RMS Titanic were made using a Remotely Operated Vehicle controlled from the surface (Magellan 725), and the first live video broadcast was made from the Titanic. [147]

- 1999 July: The Liberty Bell 7 Mercury spacecraft was recovered from 16,043 feet (4,890 m) of water in the Atlantic Ocean during the deepest commercial search and recovery operation to date. [148]

Twenty-first century

- 2001 December: The BSAC allowed rebreathers to be used in BSAC dives. [115]

- 2006 August 1: A US Navy diver in an ADS 2000 atmospheric suit established a new depth record of 2,000 feet (610 metres). [149]

- 2009 June: NAUI approved the first Standard Diving Dress recreational diving course. The course is offered in Australia.[ citation needed ]

- 2012 March: Canadian film director James Cameron piloted the Deepsea Challenger 10,898.4 metres (35,756 feet) to the bottom of the Challenger Deep, the deepest known point in the ocean. [150] [151]

- 2019: Victor Vescovo on the full ocean depth classed DSV Limiting Factor visited the deepest parts of all five oceans. [152]

- 2023 June: The fibre composite hulled Titan submersible, operated by OceanGate, was lost with all on board by implosion on a dive to the wreck of the Titanic in the Atlantic Ocean. [153] [154]