The soybean, soy bean, or soya bean is a species of legume native to East Asia, widely grown for its edible bean, which has numerous uses.

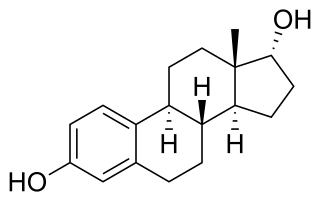

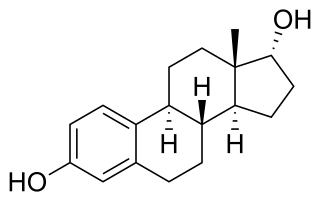

Estradiol (E2), also called oestrogen, oestradiol, is an estrogen steroid hormone and the major female sex hormone. It is involved in the regulation of female reproductive cycles such as estrous and menstrual cycles. Estradiol is responsible for the development of female secondary sexual characteristics such as the breasts, widening of the hips and a female pattern of fat distribution. It is also important in the development and maintenance of female reproductive tissues such as the mammary glands, uterus and vagina during puberty, adulthood and pregnancy. It also has important effects in many other tissues including bone, fat, skin, liver, and the brain.

Hot flashes, also known as hot flushes, are a form of flushing, often caused by the changing hormone levels that are characteristic of menopause. They are typically experienced as a feeling of intense heat with sweating and rapid heartbeat, and may typically last from two to 30 minutes for each occurrence.

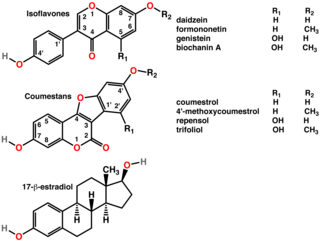

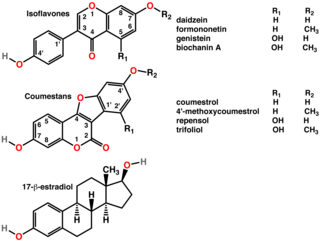

A phytoestrogen is a plant-derived xenoestrogen not generated within the endocrine system, but consumed by eating plants or manufactured foods. Also called a "dietary estrogen", it is a diverse group of naturally occurring nonsteroidal plant compounds that, because of its structural similarity to estradiol (17-β-estradiol), have the ability to cause estrogenic or antiestrogenic effects. Phytoestrogens are not essential nutrients because their absence from the diet does not cause a disease, nor are they known to participate in any normal biological function. Common foods containing phytoestrogens are soy protein, beans, oats, barley, rice, coffee, apples, carrots.

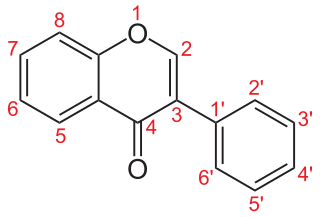

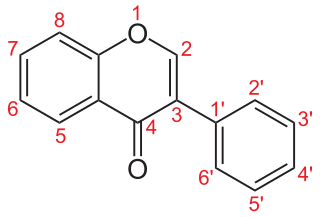

Isoflavones are substituted derivatives of isoflavone, a type of naturally occurring isoflavonoids, many of which act as phytoestrogens in mammals. Isoflavones occur in many plant species, but are especially high in soybeans.

Genistein (C15H10O5) is a naturally occurring compound that structurally belongs to a class of compounds known as isoflavones. It is described as an angiogenesis inhibitor and a phytoestrogen.

Daidzein is a naturally occurring compound found exclusively in soybeans and other legumes and structurally belongs to a class of compounds known as isoflavones. Daidzein and other isoflavones are produced in plants through the phenylpropanoid pathway of secondary metabolism and are used as signal carriers, and defense responses to pathogenic attacks. In humans, recent research has shown the viability of using daidzein in medicine for menopausal relief, osteoporosis, blood cholesterol, and lowering the risk of some hormone-related cancers, and heart disease. Despite the known health benefits, the use of both puerarin and daidzein is limited by their poor bioavailability and low water solubility.

Isoflavonoids are a class of flavonoid phenolic compounds, many of which are biologically active. Isoflavonoids and their derivatives are sometimes referred to as phytoestrogens, as many isoflavonoid compounds have biological effects via the estrogen receptor.

Estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) also known as NR3A2 is one of two main types of estrogen receptor—a nuclear receptor which is activated by the sex hormone estrogen. In humans ERβ is encoded by the ESR2 gene.

Enterolactone is an organic compound classified as an enterolignan. It is formed by the action of intestinal bacteria on plant lignan precursors present in the diet.

3β-Androstanediol, also known as 5α-androstane-3β,17β-diol, and sometimes shortened in the literature to 3β-diol, is an endogenous steroid hormone and a metabolite of androgens like dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT).

8-Prenylnaringenin (8-PN; also known as flavaprenin, (S)-8-dimethylallylnaringenin, hopein, or sophoraflavanone B) is a prenylflavonoid phytoestrogen. It is reported to be the most estrogenic phytoestrogen known. The compound is equipotent at the two forms of estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ, and it acts as a full agonist of ERα. Its effects are similar to those of estradiol, but it is considerably less potent in comparison.

Neurodegenerative diseases can disrupt the normal human homeostasis and result in abnormal estrogen levels. For example, neurodegenerative diseases can cause different physiological effects in males and females. In particular, estrogen studies have revealed complex interactions with neurodegenerative diseases. Estrogen was initially proposed to be a possible treatment for certain types of neurodegenerative diseases but a plethora of harmful side effects such as increased susceptibility to breast cancer and coronary heart disease overshadowed any beneficial outcomes. On the other hand, Estrogen Replacement Therapy has shown some positive effects with postmenopausal women. Estrogen and estrogen-like molecules form a large family of potentially beneficial alternatives that can have dramatic effects on human homeostasis and disease. Subsequently, large-scale efforts were initiated to screen for useful estrogen family molecules. Furthermore, scientists discovered new ways to synthesize estrogen-like compounds that can avoid many side effects. These are called nonsteroidal estrogens, which come from natural or synthetic products including plants, fungi, and chemicals.

17α-Estradiol is a minor and weak endogenous steroidal estrogen that is related to 17β-estradiol. It is the C17 epimer of estradiol. It has approximately 100-fold lower estrogenic potency than 17β-estradiol. The compound shows preferential affinity for the ERα over the ERβ. Although 17α-estradiol is far weaker than 17β-estradiol as an agonist of the nuclear estrogen receptors, it has been found to bind to and activate the brain-expressed ER-X with a greater potency than that of 17β-estradiol, suggesting that it may be the predominant endogenous ligand for the receptor.

A nonsteroidal estrogen is an estrogen with a nonsteroidal chemical structure. The most well-known example is the stilbestrol estrogen diethylstilbestrol (DES). Although nonsteroidal estrogens formerly had an important place in medicine, they have gradually fallen out of favor following the discovery of toxicities associated with high-dose DES starting in the early 1970s, and are now almost never used. On the other hand, virtually all selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are nonsteroidal, with triphenylethylenes like tamoxifen and clomifene having been derived from DES, and these drugs remain widely used in medicine for the treatment of breast cancer among other indications. In addition to pharmaceutical drugs, many xenoestrogens, including phytoestrogens, mycoestrogens, and synthetic endocrine disruptors like bisphenol A, are nonsteroidal substances with estrogenic activity.

O-Desmethylangolensin (O-DMA) is a phytoestrogen. It is an intestinal bacterial metabolite of the soy phytoestrogen daidzein. It produced in some people, deemed O-DMA producers, but not others. O-DMA producers were associated with 69% greater mammographic density and 6% bone density.

Estradiol glucuronide, or estradiol 17β-D-glucuronide, is a conjugated metabolite of estradiol. It is formed from estradiol in the liver by UDP-glucuronyltransferase via attachment of glucuronic acid and is eventually excreted in the urine by the kidneys. It has much higher water solubility than does estradiol. Glucuronides are the most abundant estrogen conjugates.

ERB-196, also known as WAY-202196, is a synthetic nonsteroidal estrogen that acts as a highly selective agonist of the ERβ. It possesses 78-fold selectivity for the ERβ over the ERα. The drug was under development by Wyeth for the treatment of inflammation and sepsis starting in 2004 but development was discontinued by 2011.

Slackia isoflavoniconvertens is a bacterium from the genus of Slackia which has been isolated from faeces of a human from Nuthetal in Germany. Slackia isoflavoniconvertens can metabolize daidzein and genistein, two compounds in the class of isoflavones.

4-Methoxyestriol (4-MeO-E3) is an endogenous estrogen metabolite. It is the 4-methyl ether of 4-hydroxyestriol and a metabolite of estriol and 4-hydroxyestriol. 4-Methoxyestriol has very low affinities for the estrogen receptors. Its relative binding affinities (RBAs) for estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) are both about 1% of those of estradiol. For comparison, estriol had RBAs of 11% and 35%, respectively.