A progestogen, also referred to as a progestagen, gestagen, or gestogen, is a type of medication which produces effects similar to those of the natural female sex hormone progesterone in the body. A progestin is a synthetic progestogen. Progestogens are used most commonly in hormonal birth control and menopausal hormone therapy. They can also be used in the treatment of gynecological conditions, to support fertility and pregnancy, to lower sex hormone levels for various purposes, and for other indications. Progestogens are used alone or in combination with estrogens. They are available in a wide variety of formulations and for use by many different routes of administration. Examples of progestogens include natural or bioidentical progesterone as well as progestins such as medroxyprogesterone acetate and norethisterone.

Diethylstilbestrol (DES), also known as stilbestrol or stilboestrol, is a nonsteroidal estrogen medication, which is presently rarely used. In the past, it was widely used for a variety of indications, including pregnancy support for those with a history of recurrent miscarriage, hormone therapy for menopausal symptoms and estrogen deficiency, treatment of prostate cancer and breast cancer, and other uses. By 2007, it was only used in the treatment of prostate cancer and breast cancer. In 2011, Hoover and colleagues reported on adverse health outcomes linked to DES including infertility, miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, preeclampsia, preterm birth, stillbirth, infant death, menopause prior to age 45, breast cancer, cervical cancer, and vaginal cancer. While most commonly taken by mouth, DES was available for use by other routes as well, for instance, vaginal, topical, and by injection.

Ethinylestradiol (EE) is an estrogen medication which is used widely in birth control pills in combination with progestins. In the past, EE was widely used for various indications such as the treatment of menopausal symptoms, gynecological disorders, and certain hormone-sensitive cancers. It is usually taken by mouth but is also used as a patch and vaginal ring.

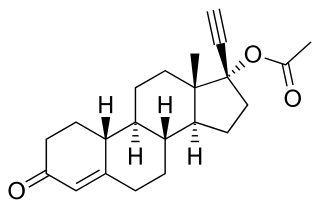

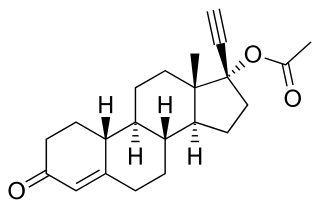

Norethisterone acetate (NETA), also known as norethindrone acetate and sold under the brand name Primolut-Nor among others, is a progestin medication which is used in birth control pills, menopausal hormone therapy, and for the treatment of gynecological disorders. The medication available in low-dose and high-dose formulations and is used alone or in combination with an estrogen. It is ingested orally.

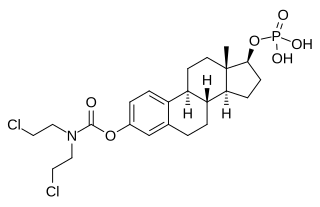

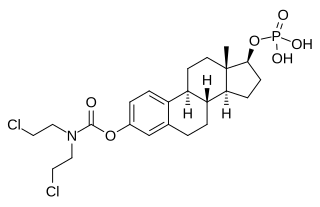

Estramustine phosphate (EMP), also known as estradiol normustine phosphate and sold under the brand names Emcyt and Estracyt, is a dual estrogen and chemotherapy medication which is used in the treatment of prostate cancer in men. It is taken multiple times a day by mouth or by injection into a vein.

Dydrogesterone, sold under the brand name Duphaston & Dydroboon among others, is a progestin medication which is used for a variety of indications, including threatened or recurrent miscarriage during pregnancy, dysfunctional bleeding, infertility due to luteal insufficiency, dysmenorrhea, endometriosis, secondary amenorrhea, irregular cycles, premenstrual syndrome, and as a component of menopausal hormone therapy. It is taken by mouth.

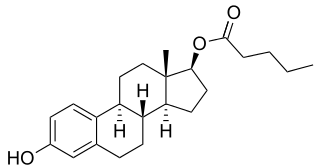

Hydroxyprogesterone caproate (OHPC), sold under the brand names Proluton and Makena among others, is a progestin medication which is used to prevent preterm birth in pregnant women with a history of the condition and to treat gynecological disorders. It has also been formulated in combination with estrogens for various indications and as a form of long-lasting injectable birth control. It is not used by mouth and is instead given by injection into muscle or fat, typically once per week to once per month depending on the indication.

Feminizing hormone therapy, also known as transfeminine hormone therapy, is hormone therapy and sex reassignment therapy to change the secondary sex characteristics of transgender people from masculine or androgynous to feminine. It is a common type of transgender hormone therapy and is used to treat transgender women and non-binary transfeminine individuals. Some, in particular intersex people but also some non-transgender people, take this form of therapy according to their personal needs and preferences.

Dienogest, sold under the brand name Visanne among others, is a progestin medication which is used in birth control pills and in the treatment of endometriosis. It is also used in menopausal hormone therapy and to treat heavy periods. Dienogest is available both alone and in combination with estrogens. It is taken by mouth.

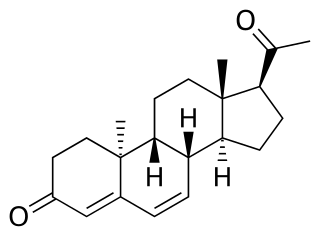

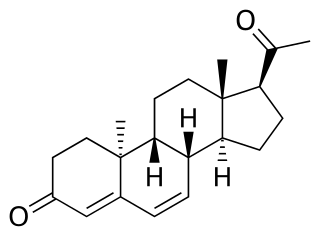

Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), also known as depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) in injectable form and sold under the brand name Depo-Provera among others, is a hormonal medication of the progestin type. It is used as a method of birth control and as a part of menopausal hormone therapy. It is also used to treat endometriosis, abnormal uterine bleeding, abnormal sexuality in males, and certain types of cancer. The medication is available both alone and in combination with an estrogen. It is taken by mouth, used under the tongue, or by injection into a muscle or fat.

Nomegestrol acetate (NOMAC), sold under the brand names Lutenyl and Zoely among others, is a progestin medication which is used in birth control pills, menopausal hormone therapy, and for the treatment of gynecological disorders. It is available both alone and in combination with an estrogen. NOMAC is taken by mouth. A birth control implant for placement under the skin was also developed but ultimately was not marketed.

Estradiol undecylate, also known as estradiol undecanoate and formerly sold under the brand names Delestrec and Progynon Depot 100 among others, is an estrogen medication which has been used in the treatment of prostate cancer in men. It has also been used as a part of hormone therapy for transgender women. Although estradiol undecylate has been used in the past, it was discontinued and hence is no longer available. The medication has been given by injection into muscle usually once a month.

Conjugated estrogens (CEs), or conjugated equine estrogens (CEEs), sold under the brand name Premarin among others, is an estrogen medication which is used in menopausal hormone therapy and for various other indications. It is a mixture of the sodium salts of estrogen conjugates found in horses, such as estrone sulfate and equilin sulfate. CEEs are available in the form of both natural preparations manufactured from the urine of pregnant mares and fully synthetic replications of the natural preparations. They are formulated both alone and in combination with progestins such as medroxyprogesterone acetate. CEEs are usually taken by mouth, but can also be given by application to the skin or vagina as a cream or by injection into a blood vessel or muscle.

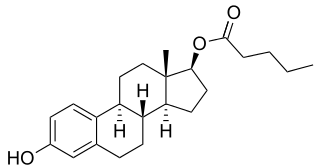

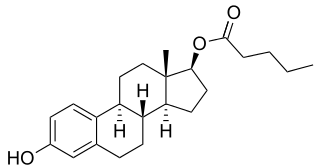

Estradiol (E2) is a medication and naturally occurring steroid hormone. It is an estrogen and is used mainly in menopausal hormone therapy and to treat low sex hormone levels in women. It is also used in hormonal birth control for women, in hormone therapy for transgender women, and in the treatment of hormone-sensitive cancers like prostate cancer in men and breast cancer in women, among other uses. Estradiol can be taken by mouth, held and dissolved under the tongue, as a gel or patch that is applied to the skin, in through the vagina, by injection into muscle or fat, or through the use of an implant that is placed into fat, among other routes.

Progesterone (P4) is a medication and naturally occurring steroid hormone. It is a progestogen and is used in combination with estrogens mainly in hormone therapy for menopausal symptoms and low sex hormone levels in women. It is also used in women to support pregnancy and fertility and to treat gynecological disorders. Progesterone can be taken by mouth, in through the vagina, and by injection into muscle or fat, among other routes. A progesterone vaginal ring and progesterone intrauterine device used for birth control also exist in some areas of the world.

An estrogen (E) is a type of medication which is used most commonly in hormonal birth control and menopausal hormone therapy, and as part of feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women. They can also be used in the treatment of hormone-sensitive cancers like breast cancer and prostate cancer and for various other indications. Estrogens are used alone or in combination with progestogens. They are available in a wide variety of formulations and for use by many different routes of administration. Examples of estrogens include bioidentical estradiol, natural conjugated estrogens, synthetic steroidal estrogens like ethinylestradiol, and synthetic nonsteroidal estrogens like diethylstilbestrol. Estrogens are one of three types of sex hormone agonists, the others being androgens/anabolic steroids like testosterone and progestogens like progesterone.

The pharmacology of estradiol, an estrogen medication and naturally occurring steroid hormone, concerns its pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, and various routes of administration.

Estradiol valerate/hydroxyprogesterone caproate (EV/OHPC), sold under the brand names Gravibinon and Injectable No. 1 among others, is a combined estrogen and progestogen medication which is used in the treatment of threatened miscarriage and other indications and as a form of combined injectable birth control to prevent pregnancy. It contains estradiol valerate (EV), an estrogen, and hydroxyprogesterone caproate (OHPC), a progestin. The medication is given by injection into muscle once a day to once a month depending on the indication.

Estradiol valerate/gestonorone caproate (EV/GC), known by the developmental code names SH-834 and SH-8.0834, is a high-dose combination medication of estradiol valerate (EV), an estrogen, and gestonorone caproate, a progestin, which was developed and studied by Schering in the 1960s and 1970s for potential use in the treatment of breast cancer in women but was ultimately never marketed. It contained 90 mg EV and 300 mg GC in each 3 mL of oil solution and was intended for use by intramuscular injection once a week. The combination has also been studied incidentally in the treatment of ovarian cancer.