Structure and bonding

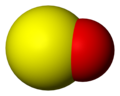

The SO molecule has a triplet ground state similar to O2 and S2, that is, each molecule has two unpaired electrons. [2] The S−O bond length of 148.1 pm is similar to that found in lower sulfur oxides (e.g. S8O, S−O = 148 pm) but is longer than the S−O bond in gaseous S2O (146 pm), SO2 (143.1 pm) and SO3 (142 pm). [2]

The molecule is excited with near infrared radiation to the singlet state (with no unpaired electrons). The singlet state is believed to be more reactive than the ground triplet state, in the same way that singlet oxygen is more reactive than triplet oxygen. [3]

Production and reactions

The SO molecule is thermodynamically unstable, converting initially to S2O2. [2] Consequently controlled syntheses typically do not detect the presence of SO proper, but instead the reaction of a chemical trap or the terminal decomposition products of S2O2 (sulfur and sulfur dioxide).

Production of SO as a reagent in organic syntheses has centred on using compounds that "extrude" SO. Examples include the decomposition of the relatively simple molecule ethylene episulfoxide: [4]

- C2H4SO → C2H4 + SO

Yields directly from an episulfoxide are poor, and improve only moderately when the carbons are sterically shielded. [5] A much better approach decomposes a diaryl cyclic trisulfide oxide, C10H6S3O, produced from naphthalene-1,8-dithiol [ wd ] and thionyl chloride. [6]

SO inserts into alkenes and alkynes to produce thiirane oxides and thiirene S-oxides respectively. It reacts with dienes to produce 2,5-dihydrothiophene [ wd ]S-oxides. [7]

Sulfur monoxide may form transiently during the metallic reduction of thionyl bromide. [8]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.