A prayer wheel is a cylindrical wheel on a spindle made from metal, wood, stone, leather or coarse cotton. Traditionally, the mantra Om Mani Padme Hum is written in Newari language of Nepal, on the outside of the wheel. Also sometimes depicted are Dakinis, Protectors and very often the 8 auspicious symbols Ashtamangala. At the core of the cylinder is a "Life Tree" often made of wood or metal with certain mantras written on or wrapped around it. Many thousands of mantras are then wrapped around this life tree. The Mantra Om Mani Padme Hum is most commonly used, but other mantras may be used as well. According to the Tibetan Buddhist tradition based on the lineage texts regarding prayer wheels, spinning such a wheel will have much the same meritorious effect as orally reciting the prayers.

Tibetan Buddhism is the form of Buddhism named after the lands of Tibet where it is the dominant religion. It is also found in the regions surrounding the Himalayas, much of Chinese Central Asia, the Southern Siberian regions such as Tuva, as well as in Mongolia.

Amitābha, also known as Amida or Amitāyus, is a celestial buddha according to the scriptures of Mahayana Buddhism. Amitābha is the principal buddha in Pure Land Buddhism, a branch of East Asian Buddhism. In Vajrayana Buddhism, Amitābha is known for his longevity attribute, magnetising red fire element, the aggregate of discernment, pure perception and the deep awareness of emptiness of phenomena. According to these scriptures, Amitābha possesses infinite merit resulting from good deeds over countless past lives as a bodhisattva named Dharmakāra. Amitābha means "Infinite Light", and Amitāyus means "Infinite Life" so Amitābha is also called "The Buddha of Immeasurable Light and Life".

Śūnyatā – pronounced in English as (shoon-ya-ta), translated most often as emptiness and sometimes voidness – is a Buddhist concept which has multiple meanings depending on its doctrinal context. It is either an ontological feature of reality, a meditative state, or a phenomenological analysis of experience.

Avalokiteśvara or Padmapani is a bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas. This bodhisattva is variably depicted, described and portrayed in different cultures as either male or female. In Tibet, he is known as Chenrezik, and in Cambodia as "អវលោកិតេស្វរៈ". In Chinese Buddhism, Avalokiteśvara has evolved into the somewhat different female figure Guanyin, also known in Japan as Kanzeon or Kannon. In Nepal Mandal this figure is known as Jana Baha Dyah, Karunamaya, Seto Machindranath.

The Heart Sūtra is a popular sutra in Mahāyāna Buddhism. Its Sanskrit title, Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya, can be translated as "The Heart of the Perfection of Wisdom".

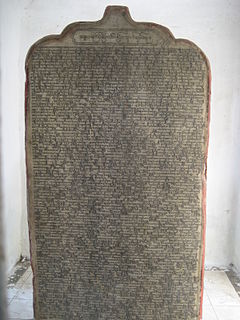

Buddhist texts were initially passed on orally by monks, but were later written down and composed as manuscripts in various Indo-Aryan languages which were then translated into other local languages as Buddhism spread. They can be categorized in a number of ways. The Western terms "scripture" and "canonical" are applied to Buddhism in inconsistent ways by Western scholars: for example, one authority refers to "scriptures and other canonical texts", while another says that scriptures can be categorized into canonical, commentarial and pseudo-canonical. Buddhist traditions have generally divided these texts with their own categories and divisions, such as that between buddhavacana "word of the Buddha," many of which are known as "sutras," and other texts, such as shastras (treatises) or Abhidharma.

Mañjuśrī is a bodhisattva associated with prajñā (insight) in Mahayana Buddhism. In Tibetan Buddhism, he is also a yidam. His name means "Gentle Glory" in Sanskrit. Mañjuśrī is also known by the fuller name of Mañjuśrīkumārabhūta, literally "Mañjuśrī, Still a Youth" or, less literally, "Prince Mañjuśrī". Other deity name of Mañjuśrī is Manjughosha.

Auṃ maṇi padme hūṃ is the six-syllabled Sanskrit mantra particularly associated with the four-armed Shadakshari form of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. It first appears in the Mahayana Kāraṇḍavyūhasūtra where it is also referred to as the sadaksara and the paramahrdaya, or “innermost heart” of Avalokiteshvara. In this text the mantra is seen as condensed form of all the Buddhist teachings.

The Dharmaguptaka are one of the eighteen or twenty early Buddhist schools, depending on the source. They are said to have originated from another sect, the Mahīśāsakas. The Dharmaguptakas had a prominent role in early Central Asian and Chinese Buddhism, and their Prātimokṣa are still in effect in East Asian countries to this day, including China, Vietnam, Korea, and Japan. They are one of three surviving Vinaya lineages, along with that of the Theravāda and the Mūlasarvāstivāda.

A thangka, variously spelt as thangka, tangka, thanka, or tanka, is a Tibetan Buddhist painting on cotton, silk appliqué, usually depicting a Buddhist deity, scene, or mandala. Thangkas are traditionally kept unframed and rolled up when not on display, mounted on a textile backing somewhat in the style of Chinese scroll paintings, with a further silk cover on the front. So treated, thangkas can last a long time, but because of their delicate nature, they have to be kept in dry places where moisture will not affect the quality of the silk. Most thangkas are relatively small, comparable in size to a Western half-length portrait, but some are extremely large, several metres in each dimension; these were designed to be displayed, typically for very brief periods on a monastery wall, as part of religious festivals. Most thangkas were intended for personal meditation or instruction of monastic students. They often have elaborate compositions including many very small figures. A central deity is often surrounded by other identified figures in a symmetrical composition. Narrative scenes are less common, but do appear.

Buddhism in Nepal started spreading since the reign of Ashoka through Indian and Tibetan missionaries. The Kiratas were the first people in Nepal who embraced Gautama Buddha’s teachings, followed by the Licchavis and Newars. Buddha was born in Lumbini in the Shakya Kingdom. Lumbini is considered to lie in present-day Rupandehi district, Lumbini zone of Nepal. Buddhism is the second-largest religion in Nepal. According to 2011 census, the Buddhist population in Nepal is 9% of the country population. It has not been possible to assign with certainty the year in which Prince Siddhartha, the birth name of the Buddha, was born, it is usually placed at around 563 BCE. According to 2001 census, 10.74% of Nepal's population practice Buddhism, consisting mainly of Tibeto-Burman-speaking ethnicities, the Newar. In Nepal's hill and mountain regions Hinduism has absorbed Buddhist tenets to such an extent that in many cases they have shared deities as well as temples. For instance, the Muktinath Temple is sacred and a common house of worship for both Hindus and Buddhists.

The expression Nepalese Scripts refers to alphabetic writing systems employed historically in Nepala Mandala by the indigenous Newars for primarily writing Nepalbhasa and for transcribing Sanskrit. There are also some claims they have also been used to write the Parbatiya (Khas) language but all Pahari languages were traditionally written with the Takri alphabet and now Devanagari.

In epigraphy, a bilingual is an inscription that includes the same text in two languages. Bilinguals are important for the decipherment of ancient writing systems, and for the study of ancient languages with small or repetitive corpora.

Prayer Wheels are widely used in Tibet and areas where Tibetan culture is predominant.

The Shurangama or Śūraṅgama mantra is a dhāraṇī or long mantra of Buddhist practice in China, Japan and Korea. Although relatively unknown in modern Tibet, there are several Śūraṅgama Mantra texts in the Tibetan Buddhist canon. It is associated with Chinese Esoteric Buddhism and Shingon Buddhism.

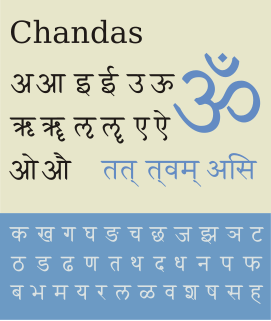

Sanskrit Buddhist literature refers to Buddhist texts composed either in classical Sanskrit, or in a register that has been called "Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit" (BHS), or a mixture of the two. Several non-Mahāyāna Nikāyas appear to have kept their canons in Sanskrit, most prominent among which was the Sarvāstivāda. The Mahāyāna Sūtras are also in Sanskrit, with less classical registers prevalent in the gāthā portions. Buddhist Tantras too are written in Sanskrit, sometimes interspersed with Apabhramśa, and often containing notable irregularities in grammar and meter.

Dānapāla or Shihu (?–1017) was an Indian Buddhist monk and prolific translator of Sanskrit Buddhist sutras during the Song dynasty in China.