Balkh is a town in the Balkh Province of Afghanistan. It is located approximately 20 kilometres (12 mi) to the northwest of the provincial capital city Mazar-i-Sharif and approximately 74 kilometres (46 mi) to the south of the Amu Darya and the Afghanistan–Uzbekistan border. In 2021–2022, the National Statistics and Information Authority reported that the town had 138,594 residents. Listed as the eighth largest settlement in the country, unofficial 2024 estimates set its population at around 114,883 people.

The Kambojas were a southeastern Iranian people who inhabited the northeastern most part of the territory populated by Iranian tribes, which bordered the Indian lands. They only appear in Indo-Aryan inscriptions and literature, being first attested during the later part of the Vedic period.

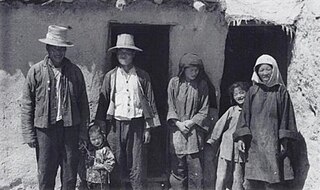

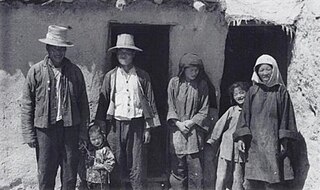

Tibetan Muslims, also known as the Khache, are Tibetans who adhere to Islam. Many are descendants of Kashmiris, Ladakhis, and Nepalis who arrived in Tibet in the 14th to 17th centuries. There are approximately 5,000 Tibetan Muslims living in China, over 1,500 in India, and 300 to 400 in Nepal.

Tokharistan is an ancient Early Middle Ages name given to the area which was known as Bactria in Ancient Greek sources.

Buddhism has a long history in Indonesia, and it is one of the six recognized religions in the country, along with Islam, Christianity, Hinduism and Confucianism. According to 2023 estimates roughly 0.71% of the total citizens of Indonesia were Buddhists, numbering around 2 million. Most Buddhists are concentrated in Jakarta, Riau, Riau Islands, Bangka Belitung, North Sumatra, and West Kalimantan. These totals, however, are probably inflated, as practitioners of Taoism and Chinese folk religion, which are not considered official religions of Indonesia, likely declared themselves as Buddhists on the most recent census. Today, the majority of Buddhists in Indonesia are Chinese and other East Asians, but small communities of native Buddhists also exist.

Buddhism, a religion founded by Gautama Buddha, first arrived in modern-day Afghanistan through the conquests of Ashoka, the third emperor of the Maurya Empire. Among the earliest notable sites of Buddhist influence in the country is a bilingual mountainside inscription in Greek and Aramaic that dates back to 260 BCE and was found on the rocky outcrop of Chil Zena near Kandahar.

Jaʽfar ibn Yahya Barmaki or Jafar al-Barmaki (767–803), also called Aba-Fadl, was a Persian vizier of the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid, succeeding his father in that position. He was a member of the influential Barmakid family, formerly Buddhist leaders of the Nava Vihara monastery. He was executed in 803 at the orders of Harun al-Rashid.

The Nava Vihāra were two Buddhist monasteries close to the ancient city of Balkh in northern Afghanistan. Historical accounts report it as flourishing as an important centre of Buddhism between the seventh and eleventh centuries CE. It may have been founded considerably earlier, perhaps in or after the reign of the Kushan emperor Kaniṣka, in the second century CE.

Many adherents of Buddhism have experienced religious persecution because of their adherence to the Buddhist practice, including unwarranted arrests, imprisonment, beating, torture, and/or execution. The term also may be used in reference to the confiscation or destruction of property, temples, monasteries, centers of learning, meditation centers, historical sites, or the incitement of hatred towards Buddhists.

Buddhism in Central Asia mainly existed in Mahayana forms and was historically especially prevalent along the Silk Road. The history of Buddhism in Central Asia is closely related to the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism during the first millennium of the common era. It has been argued that the spread of Indian culture and religions, especially Buddhism, as far as Sogdia, corresponded to the rule of the Kidarites over the regions from Sogdia to Gandhara.

Kalafgan District is a district of Takhar Province, Afghanistan. The district is well governed, with self-governance in parts of Kalafgan because of how remote they are. 42 villages are located in the district. In 2017, Kalafgan was considered to be under full control by the Afghan Government. However, the Taliban had taken full control by August 2021.

Buddhism in Iran dates back to the 2nd century, when Parthian Buddhist missionaries, such as An Shigao and An Xuan, were active in spreading Buddhism in China. Many of the earliest translators of Buddhist literature into Chinese were from Parthia and other kingdoms linked with present-day Iran.

Trapusa and Bahalika are traditionally regarded as the first disciples of the Buddha. The first account of Trapusa and Bahalika appears in the Vinaya section of the Tripiṭaka where they offer the Buddha his first meal after enlightenment, take refuge in the Dharma, and become the Buddha's first disciples. According to the Pali canon, they were caravan drivers from Puṣkalāvatī, in ukkalapada on way to Uttarapatha. However, most ancient Buddhist texts state that they came from Orissa or Burma i.e. modern Myanmar. Xuanzang (玄奘) says that Buddhism was brought to Central Asia by Trapusa and Bahalika, two Burmese merchants who offered food to the Buddha after his enlightenment.

Turkic peoples began settling in the Tarim Basin in the 7th century. The area was later settled by the Turkic Uyghurs, who founded the Qocho Kingdom there in the 9th century. The historical area of what is modern-day Xinjiang in China consisted of the distinct areas of the Tarim Basin and Dzungaria. The area was first populated by the Tocharians and the Saka, who were Indo-Europeans and practiced Buddhism. The Tocharian and Saka peoples came under Xiongnu and then Chinese rule during the Han dynasty as the Protectorate of the Western Regions due to wars between the Han dynasty and the Xiongnu. The First Turkic Khaganate conquered this region in 560, and in 603, after a series of civil wars, the First Turkic Khaganate was separated into the Eastern Turkic Khaganate and the Western Turkic Khaganate, with Xinjiang coming under the latter. The region then became part of the Tang dynasty as the Protectorate General to Pacify the West after the Tang campaigns against the Western Turks. The Tang dynasty withdrew its control of the region in the Protectorate General to Pacify the West and the Four Garrisons of Anxi after the An Lushan Rebellion, after which the Turkic peoples and the other native inhabitants living in the area gradually converted to Islam following Arab incursions into Central Asia.

The Tokhara Yabghus or Yabghus of Tokharistan were a dynasty of Western Turk–Hephtalite sub-kings with the title "Yabghus", who ruled from 625 CE in the area of Tokharistan north and south of the Oxus River, with some smaller remnants surviving in the area of Badakhshan until 758 CE. Their legacy extended to the southeast where it came into contact with the Turk Shahis and the Zunbils until the 9th century CE.

Tepe Sardar, also Tapa Sardar or Tepe-e-Sardar, is an ancient Buddhist monastery in Afghanistan. It is located near Ghazni, and it dominates the Dasht-i Manara plain. The site displays two major artistic phases, an Hellenistic phase during the 3rd to 6th century CE, followed by a Sinicized-Indian phase during the 7th to 9th century.

Anna Ayșe Akasoy is a German orientalist and professor of Islamic intellectual history at the Graduate Center, CUNY. Akasoy works on the intellectual history of Islam, especially of al-Andalus, on Islamic philosophy as well as on Arab veterinary medicine, falconry and hunting.

Barha Tegin was the first ruler of the Turk Shahis. He is only known in name from the accounts of the Muslim historian Al-Biruni and reconstructions from Chinese sources, and the identification of his coinage remains conjectural.

Khingala, also transliterated Khinkhil, Khinjil or Khinjal, was a ruler of the Turk Shahis. He is only known in name from the accounts of the Muslim historian Ya'qubi and from an epigraphical source, the Gardez Ganesha. The identification of his coinage remains conjectural.

Bo Fuzhun, also Bofuzhun was a ruler of the Turk Shahis. He is only known in name from Chinese imperial accounts and possibly numismatic sources. The identification of his coinage remains conjectural.