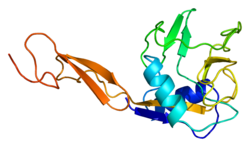

Structure

E selectin has a cassette structure: an N-terminal, C-type lectin domain, an EGF (epidermal-growth-factor)-like domain, 6 Sushi domain (SCR repeat) units, a transmembrane domain (TM) and an intracellular cytoplasmic tail (cyto). The three-dimensional structure of the ligand-binding region of human E-selectin has been determined at 2.0 Å resolution in 1994. [6] The structure reveals limited contact between the two domains and a coordination of Ca2+ not predicted from other C-type lectins. Structure/function analysis indicates a defined region and specific amino-acid side chains that may be involved in ligand binding. The E-selectin bound to sialyl-LewisX (SLeX; NeuNAcα2,3Galβ1,4[Fucα1,3]GlcNAc) tetrasaccharide was solved in 2000. [7]

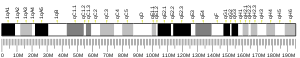

Gene and regulation

In humans, E-selectin is encoded by the SELE gene. Its C-type lectin domain, EGF-like, SCR repeats, and transmembrane domains are each encoded by separate exons, whereas the E-selectin cytosolic domain derives from two exons. The E-selectin locus flanks the L-selectin locus on chromosome 1. [8]

Different from P-selectin, which is stored in vesicles called Weibel-Palade bodies, E-selectin is not stored in the cell and has to be transcribed, translated, and transported to the cell surface. The production of E-selectin is stimulated by the expression of P-selectin which in turn, is stimulated by tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), interleukin-1 (IL-1) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS). [9] [10] It takes about two hours, after cytokine recognition, for E-selectin to be expressed on the endothelial cell's surface. Maximal expression of E-selectin occurs around 6–12 hours after cytokine stimulation, and levels returns to baseline within 24 hours. [10]

Shear forces are also found to affect E-selectin expression. A high laminar shear enhances acute endothelial cell response to interleukin-1β in naïve or shear-conditioned endothelial cells as may be found in the pathological setting of ischemia/reperfusion injury while conferring rapid E-selectin down regulation to protect against chronic inflammation. [11]

Phytoestrogens, plant compounds with estrogen-like biological activity, such as genistein, formononetin, biochanin A and daidzein, as well as a mixture of these phytoestrogens were found able to reduce E-selectin as well as VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 on cell surface and in culture supernatant. [12]

Ligands

E-selectin recognizes and binds to sialylated carbohydrates present on the surface proteins of certain leukocytes. E-selectin ligands are expressed by neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils, memory-effector T-like lymphocytes, and natural killer cells. Each of these cell types is found in acute and chronic inflammatory sites in association with expression of E-selectin, thus implicating E-selectin in the recruitment of these cells to such inflammatory sites.

These carbohydrates include members of the Lewis X and Lewis A families found on monocytes, granulocytes, and T-lymphocytes. [13]

The glycoprotein ESL-1, present on neutrophils and myeloid cells, was the first counter-receptor for E-selectin to be described. It is a variant of the tyrosine kinase FGF glycoreceptor, raising the possibility that its binding to E-selectin is involved in initiating signaling in the bound cells.

P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1) derived from human neutrophils is also a high-efficiency ligand for endothelium-expressed E-selectin under flow. [14] It mediates the rolling of leukocytes on the activated endothelium surrounding an inflamed tissue.

Both ESL-1 and PSGL-1 should bear sialyl Lewis a/x in order to bind E/P-selectins. [15]

E-selectin is found to mediate the adhesion of tumor cells to endothelial cells, by binding to E-selectin ligands on the tumor cells. E-selectin ligands also play a role in cancer metastasis. The role of these two E-selectin ligands in metastasis in vivo is poorly defined and remains to be firmly demonstrated. PSGL-1 was detected on the surfaces of bone-metastatic prostate tumor cells, suggesting that it may have a functional role in the bone tropism of prostate tumor cells. [16]

In cancer cells, CD44, death receptor-3 (DR3), LAMP1, and LAMP2 were identified as E-selectin ligands present on colon cancer cells, [17] and CD44v, Mac2-BP, and gangliosides were identified as E-selectin ligands present on breast cancer cells. [18] [19] [20]

On human neutrophils the glycosphingolipid NeuAcα2-3Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3[Galβ1-4(Fucα1-3)GlcNAcβ1-3]2[Galβ1-4GlcNAcβ1-3]2Galβ1-4GlcβCer (and closely related structures) are functional E-selectin receptors. [21]

Function

Role in inflammation

During inflammation, E-selectin plays an important part in recruiting leukocytes to the site of injury. The local release of cytokines IL-1 and TNF-α by macrophages in the inflamed tissue induces the over-expression of E-selectin on endothelial cells of nearby blood vessels. [22] Leukocytes in the blood expressing the correct ligand will bind with low affinity to E-selectin, also under the shear stress of blood flow, causing the leukocytes to "roll" along the internal surface of the blood vessel as temporary interactions are made and broken.

As the inflammatory response progresses, chemokines released by injured tissue enter the blood vessels and activate the rolling leukocytes, which are now able to tightly bind to the endothelial surface and begin making their way into the tissue. [13]

P-selectin has a similar function, but is expressed on the endothelial cell surface within minutes as it is stored within the cell rather than produced on demand. [13]

Role in cancer

E-selectin was first discovered as an transmembrane receptor induced in endothelial cells upon inflammatory stimulation which mediated adhesion of monocytic or HL60 leukemic cells. [23] [24] This led to the hypothesis that cancer cells secreted inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β or TNFα to induce E-selectin at distant metastatic sites. This induction would enable circulating tumor cells to arrest at stimulated sites, roll along activated endothelium, extravasate, and form metastases. [25] Studies since have shown that E-selectin binding to colon cancer cells correlates with increasing metastatic potential, [26] and that cancer cells of multiple tumor types bind E-selectin using glycoprotein or glycolipid ligands normally expressed on immune cells. [27] [28] Studies have further described a mechanistic cascade wherein cancer cells first bind E-selectin at shear flow rates: E-selectin binding results in a velcro-like interaction allowing the cancer cells to engage higher affinity integrin binding that eventually results in a tight binding between tumor cells and the activated endothelium. [29] [30]

While numerous pieces of in vitro and clinical evidence continue to support this hypothesis of E-selectin-mediated cancer metastasis, in vivo studies of cancer metastasis have shown that E-selectin knockout only minimally affects leukemic cell adhesion to bone immediately following injection. [31] while experimental lung metastasis is not affected by the genetic deletion of E-selectin. [32] [33] Furthermore, studies have also shown that primary tumor growth is increased in E-selectin knockout mice. [34] [35] This paradox was more recently solved by a trio of studies showing that E-selectin is only constitutively expressed in the bone marrow endothelium [36] where it is thought to perform functions vital to hematopoiesis. [37] that are hijacked specifically by cells metastasizing to bone and not other sites. [38] This data supports ongoing clinical efforts to inhibit breast cancer bone metastasis with E-selectin-blocking agents. [39] The complexity of E-selectin ligand biology may also play a role in these discrepant in vitro and in vivo results. At least 15 different glycoprotein and glycolipid substrates for E-selectin have been described on various cancer cells, while only n-glycan Glg1 (Esl1) was shown to mediate bone metastasis. [40] Other ligands or combinations thereof may result in distinct mechanisms during cancer metastasis.

Beyond a direct interaction with tumor cells, E-selectin induction in response to cytokines locally secreted by cancer cells enables specific tumor targeting of sLeX-conjugated nanoparticles or thioaptamers containing anti-tumor payloads. [41] In addition, E-selectin may also function to recruit monocytes to primary tumors or lung metastases to promote an inflammatory pro-tumor microenvironment. [42] Blocking these interactions or enabling trafficking of CAR-T cells to E-selectin-positive sites may hold promise for future therapeutic development.

Pathological relevance

Critical illness polyneuromyopathy

In cases of elevated blood glucose levels, such as in sepsis, E-selectin expression is higher than normal, resulting in greater microvascular permeability. The greater permeability leads to edema (swelling) of the skeletal endothelium (blood vessel linings), resulting in skeletal muscle ischemia (restricted blood supply) and eventually necrosis (cell death). This underlying pathology is the cause of the symptomatic disease critical illness polyneuromyopathy (CIPNM). [43] Traditional Chinese herbal medicines, like berberine downregulate E-selectin. [44]

Pathogen attachment

Study shows the adherence of Porphyromonas gingivalis to human umbilical vein endothelial cells increases with the induction of E-selectin expression by TNF-α. An antibody to E-selectin and sialyl LewisX suppressed P. gingivalis adherence to stimulated HUVECs. P. gingivalis mutants lacking OmpA-like proteins Pgm6/7 had reduced adherence to stimulated HUVECs, but fimbriae-deficient mutants were not affected. E-selecin-mediated P. gingivalis adherence activated endothelial exocytosis. These results suggest that the interaction between host E-selectin and pathogen Pgm6/7 mediates P. gingivalis adherence to endothelial cells and may trigger vascular inflammation. [45]

Acute coronary syndrome

The immunohistochemical expressions of E-selectin and PECAM-1 were significantly increased at intima in vulnerable plaques of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) group, especially in neovascular endothelial cells, and positively correlated with inflammatory cell density, suggesting that PECAM-1 and E-selectin might play an important role in inflammatory reaction and development of vulnerable plaque. E-selectin Ser128Arg polymorphism is associated with ACS, and it might be a risk factor for ACS. [46]

Smoking is highly correlated with enhanced likelihood of atherosclerosis by inducing endothelial dysfunction. In endothelial cells, various cell-adhesion molecules including E-selectin, are shown to be upregulated upon exposure to nicotine, the addictive component of tobacco smoke. Nicotine-stimulated adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells is dependent on the activation of α7-nAChRs, β-Arr1 and cSrc regulated increase in E2F1-mediated transcription of E-selectin gene. Therefore, agents such as RRD-251 that can target activity of E2F1 may have potential therapeutic benefit against cigarette smoke induced atherosclerosis. [47]

Cerebral aneurysm

It's also found that E-selectin expression increased in human ruptured cerebral aneurysm tissues. E-selectin might be an important factor involved in the process of cerebral aneurysm formation and rupture, by promoting inflammation and weakening cerebral artery walls. [48]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.