Contents

- Synthesis

- History

- Regulation

- Toxicology

- Incidents

- James River estuary

- French Antilles

- References

- External links

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name decachloropentacyclo[5.3.0.02.6.03.9.04.8]decan-5-one [1] | |

| Other names Chlordecone Clordecone Merex CAS name: 1,1a,3,3a,4,5,5,5a,5b,6-decachlorooctahydro-1,3,4-metheno-2H-cyclobuta[cd]pentalen-2-one | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.093 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID | |

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

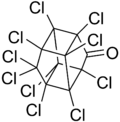

| C10Cl10O | |

| Molar mass | 490.633 g/mol |

| Appearance | tan to white crystalline solid |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 1.6 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 349 °C (660 °F; 622 K) (decomposes) |

| 0.27 g/100 mL | |

| Solubility | soluble in acetone, ketone, acetic acid slightly soluble in benzene, hexane |

| log P | 5.41 |

| Vapor pressure | 3.10−7 kPa |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 764 J/K mol |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | −225.9 kJ/mol |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards | carcinogen [2] |

| Flash point | Non-flammable [2] |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) | 95 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) | none [2] |

REL (Recommended) | Ca TWA 0.001 mg/m3 [2] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) | N.D. [2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

Chlordecone, better known in the United States under the brand name Kepone, is an organochlorine compound and a colourless solid. It is an obsolete insecticide, now prohibited in the Western world, but only after many thousands of tonnes had been produced and used. [3] Chlordecone is a known persistent organic pollutant that was banned globally by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in 2009. [4]