The ancient Aramaic alphabet was used to write the Aramaic languages spoken by ancient Aramean pre-Christian tribes throughout the Fertile Crescent. It was also adopted by other peoples as their own alphabet when empires and their subjects underwent linguistic Aramaization during a language shift for governing purposes — a precursor to Arabization centuries later — including among the Assyrians and Babylonians who permanently replaced their Akkadian language and its cuneiform script with Aramaic and its script, and among Jews, but not Samaritans, who adopted the Aramaic language as their vernacular and started using the Aramaic alphabet, which they call "Square Script", even for writing Hebrew, displacing the former Paleo-Hebrew alphabet. The modern Hebrew alphabet derives from the Aramaic alphabet, in contrast to the modern Samaritan alphabet, which derives from Paleo-Hebrew.

The Hebrew alphabet, known variously by scholars as the Ktav Ashuri, Jewish script, square script and block script, is traditionally an abjad script used in the writing of the Hebrew language and other Jewish languages, most notably Yiddish, Ladino, Judeo-Arabic, and Judeo-Persian. In modern Hebrew, vowels are increasingly introduced. It is also used informally in Israel to write Levantine Arabic, especially among Druze. It is an offshoot of the Imperial Aramaic alphabet, which flourished during the Achaemenid Empire and which itself derives from the Phoenician alphabet.

The Phoenician alphabet is an abjad used across the Mediterranean civilization of Phoenicia for most of the 1st millennium BC. It was the first alphabet ever developed, and attested in Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions found across the Mediterranean region. In the history of writing systems, the Phoenician script also marked the first to have a fixed writing direction—while previous systems were multi-directional, Phoenician was written horizontally, from right to left. It developed directly from the Proto-Sinaitic script used during the Late Bronze Age, which was derived in turn from Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Lachish was an ancient Israelite city in the Shephelah region of Canaan on the south bank of the Lakhish River mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible. The current tell by that name, known as Tel Lachish or Tell el-Duweir, has been identified with Lachish. Today, it is an Israeli national park operated and maintained by the Israel Nature and Parks Authority. It lies near the present-day moshav of Lakhish, which was named in honor of the ancient city.

Phoenician is an extinct Canaanite Semitic language originally spoken in the region surrounding the cities of Tyre and Sidon. Extensive Tyro-Sidonian trade and commercial dominance led to Phoenician becoming a lingua franca of the maritime Mediterranean during the Iron Age. The Phoenician alphabet spread to Greece during this period, where it became the source of all modern European scripts.

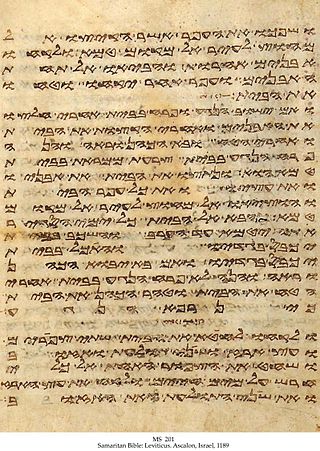

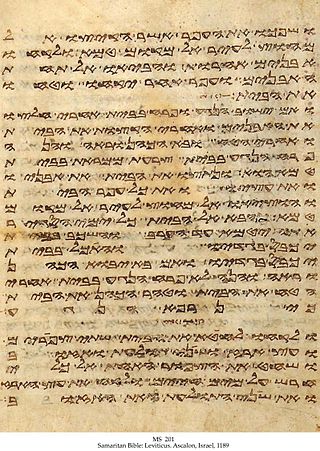

The Samaritan Hebrew script, or simply Samaritan script is used by the Samaritans for religious writings, including the Samaritan Pentateuch, writings in Samaritan Hebrew, and for commentaries and translations in Samaritan Aramaic and occasionally Arabic.

The Paleo-Hebrew script, also Palaeo-Hebrew, Proto-Hebrew or Old Hebrew, is the writing system found in Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, including pre-Biblical and Biblical Hebrew, from southern Canaan, also known as the biblical kingdoms of Israel (Samaria) and Judah. It is considered to be the script used to record the original texts of the Bible due to its similarity to the Samaritan script; the Talmud states that the Samaritans still used this script. The Talmud described it as the "Livonaʾa script", translated by some as "Lebanon script". However, it has also been suggested that the name is a corrupted form of "Neapolitan", i.e. of Nablus. Use of the term "Paleo-Hebrew alphabet" is due to a 1954 suggestion by Solomon Birnbaum, who argued that "[t]o apply the term Phoenician [from Northern Canaan, today's Lebanon] to the script of the Hebrews [from Southern Canaan, today's Israel-Palestine] is hardly suitable". The Paleo-Hebrew and Phoenician alphabets are two slight regional variants of the same script.

The Proto-Sinaitic script is a Middle Bronze Age writing system known from a small corpus of about 30-40 inscriptions and fragments from Serabit el-Khadim in the Sinai Peninsula, as well as two inscriptions from Wadi el-Hol in Middle Egypt. Together with about 20 known Proto-Canaanite inscriptions, it is also known as Early Alphabetic, i.e. the earliest trace of alphabetic writing and the common ancestor of both the Ancient South Arabian script and the Phoenician alphabet, which led to many modern alphabets including the Greek alphabet. According to common theory, Canaanites or Hyksos who spoke a Canaanite language repurposed Egyptian hieroglyphs to construct a different script.

The history of the alphabet goes back to the consonantal writing system used to write Semitic languages in the Levant during the 2nd millennium BCE. Nearly all alphabetic scripts used throughout the world today ultimately go back to this Semitic script. Its first origins can be traced back to a Proto-Sinaitic script developed in Ancient Egypt to represent the language of Semitic-speaking workers and slaves in Egypt. Unskilled in the complex hieroglyphic system used to write the Egyptian language, which required a large number of pictograms, they selected a small number of those commonly seen in their surroundings to describe the sounds, as opposed to the semantic values, of their own Canaanite language. This script was partly influenced by the older Egyptian hieratic, a cursive script related to Egyptian hieroglyphs. The Semitic alphabet became the ancestor of multiple writing systems across the Middle East, Europe, northern Africa, and South Asia, mainly through Phoenician and the closely related Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, and later Aramaic and the Nabatean—derived from the Aramaic alphabet and developed into the Arabic alphabet—five closely related members of the Semitic family of scripts that were in use during the early first millennium BCE.

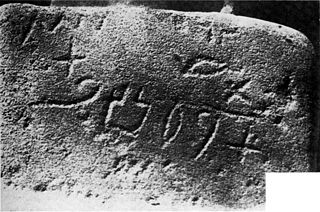

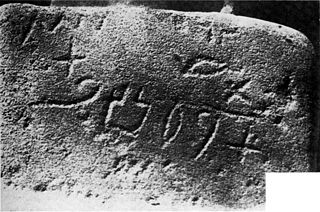

The Zayit Stone is a 38-pound (17 kg) limestone boulder dating to the 10th century BCE, discovered on 15 July 2005 at Tel Zayit (Zeitah) in the Guvrin Valley, about 50 kilometres (31 mi) southwest of Jerusalem. The boulder measures 37.5 by 27 by 15.7 centimetres and was embedded in the stone wall of a building. It is the earliest known example of the complete Phoenician or Paleo-Hebrew alphabet as it had developed after the Bronze Age collapse out of the Proto-Canaanite alphabet.

The Gezer calendar is a small limestone tablet with an early Canaanite inscription discovered in 1908 by Irish archaeologist R. A. Stewart Macalister in the ancient city of Gezer, 20 miles west of Jerusalem. It is commonly dated to the 10th century BCE, although the excavation was not stratified.

The Philistine language is the extinct language of the Philistines. Very little is known about the language, of which a handful of words survived as cultural loanwords in Biblical Hebrew, describing specifically Philistine institutions, like the seranim, the "lords" of the Philistine five cities ("pentapolis"), or the 'argáz receptacle, which occurs in 1 Samuel 6 and nowhere else, or the title padî.

Northwest Semitic is a division of the Semitic languages comprising the indigenous languages of the Levant. It emerged from Proto-Semitic in the Early Bronze Age. It is first attested in proper names identified as Amorite in the Middle Bronze Age. The oldest coherent texts are in Ugaritic, dating to the Late Bronze Age, which by the time of the Bronze Age collapse are joined by Old Aramaic, and by the Iron Age by Sutean and the Canaanite languages.

Khirbet Qeiyafa, also known as Elah Fortress and in Hebrew as Horbat Qayafa, is the site of an ancient fortress city overlooking the Elah Valley and dated to the first half of the 10th century BCE. The ruins of the fortress were uncovered in 2007, near the Israeli city of Beit Shemesh, 30 km (20 mi) from Jerusalem. It covers nearly 2.3 ha and is encircled by a 700-meter-long (2,300 ft) city wall constructed of field stones, some weighing up to eight tons. Excavations at site continued in subsequent years. A number of archaeologists, mainly the two excavators, Yosef Garfinkel and Saar Ganor, have claimed that it might be one of two biblical cities, either Sha'arayim, whose name they interpret as "Two Gates", because of the two gates discovered on the site, or Neta'im; and that the large structure at the center is an administrative building dating to the reign of King David, where he might have lodged at some point. This is based on their conclusions that the site dates to the early Iron IIA, ca. 1025–975 BCE, a range which includes the biblical date for the biblical Kingdom of David. Others suggest it might represent either a North Israelite, Philistine, or Canaanite fortress, a claim rejected by the archaeological team that excavated the site. The team's conclusion that Khirbet Qeiyafa was a fortress of King David has been criticised by some scholars. Garfinkel (2017) changed the chronology of Khirbet Qeiyafa to ca. 1000–975 BCE.

The Hebrew alphabet is a script that was derived from the Aramaic alphabet during the Persian, Hellenistic and Roman periods. It replaced the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet which was used in the earliest epigraphic records of the Hebrew language.

Yosef Garfinkel is an Israeli archaeologist and academic. He is a professor of Prehistoric Archaeology and of Archaeology of the Biblical Period at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Biblical Hebrew orthography refers to the various systems which have been used to write the Biblical Hebrew language. Biblical Hebrew has been written in a number of different writing systems over time, and in those systems its spelling and punctuation have also undergone changes.

Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples or Proto-Semitic people were speakers of Semitic languages who lived throughout the ancient Near East and North Africa, including the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Arabian Peninsula and Carthage from the 3rd millennium BC until the end of antiquity, with some, such as Arabs, Arameans, Assyrians, Jews, Mandaeans, and Samaritans having a continuum into the present day.

The Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon is a 15-by-16.5-centimetre ostracon with five lines of text, discovered in Building II, Room B, in Area B of the excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa in 2008. Hebrew University archaeologist Amihai Mazar said the inscription was the longest Proto-Canaanite text ever found. Carbon-14 dating of 4 olive pips found in the same context with the ostracon and pottery analysis offer a date of Iron Age IIA c. 3,000 years ago.