Antidepressants are a class of medications used to treat major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, chronic pain, and addiction.

An anxiolytic is a medication or other intervention that reduces anxiety. This effect is in contrast to anxiogenic agents which increase anxiety. Anxiolytic medications are used for the treatment of anxiety disorders and their related psychological and physical symptoms.

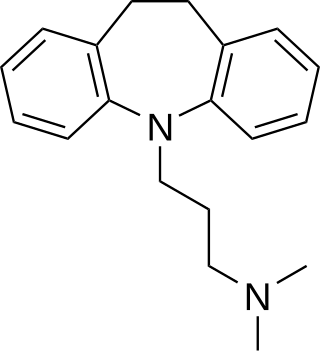

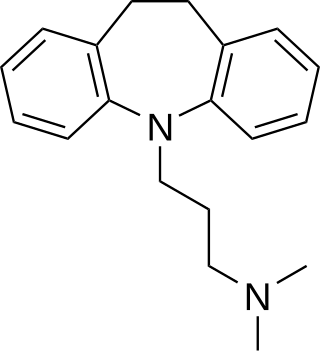

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are a class of medications that are used primarily as antidepressants. TCAs were discovered in the early 1950s and were marketed later in the decade. They are named after their chemical structure, which contains three rings of atoms. Tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs), which contain four rings of atoms, are a closely related group of antidepressant compounds.

Fluvoxamine, sold under the brand name Luvox among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class. It is primarily used to treat major depressive disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), but is also used to treat anxiety disorders such as panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

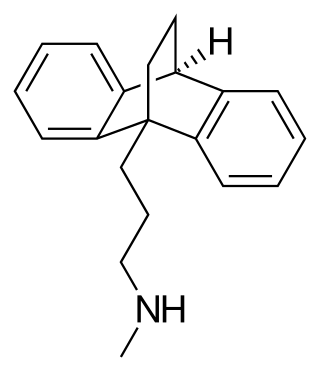

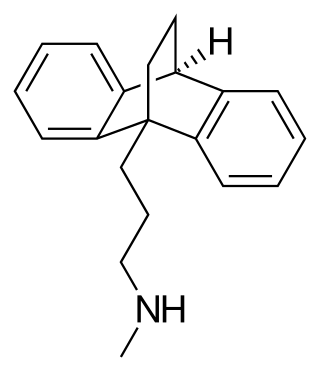

Maprotiline, sold under the brand name Ludiomil among others, is a tetracyclic antidepressant (TeCA) that is used in the treatment of depression. It may alternatively be classified as a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), specifically a secondary amine. In terms of its chemistry and pharmacology, maprotiline is closely related to such-other secondary-amine TCAs as nortriptyline and protriptyline and has similar effects to them, albeit with more distinct anxiolytic effects. Additionally, whereas protriptyline tends to be somewhat more stimulating and in any case is distinctly more-or-less non-sedating, mild degrees of sedation may be experienced with maprotiline.

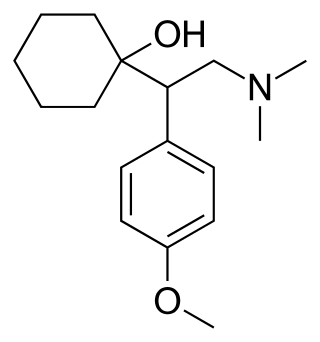

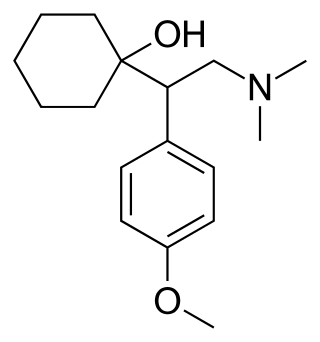

Venlafaxine, sold under the brand name Effexor among others, is an antidepressant medication of the serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) class. It is used to treat major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder. Studies have shown that venlafaxine improves post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It may also be used for chronic pain. It is taken orally. It is also available as the salt venlafaxine besylate in an extended-release formulation.

Mirtazapine, sold under the brand name Remeron among others, is an atypical tetracyclic antidepressant, and as such is used primarily to treat depression. Its effects may take up to four weeks but can also manifest as early as one to two weeks. It is often used in cases of depression complicated by anxiety or insomnia. The effectiveness of mirtazapine is comparable to other commonly prescribed antidepressants. It is taken by mouth.

Duloxetine, sold under the brand name Cymbalta among others, is a medication used to treat major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, fibromyalgia, neuropathic pain and central sensitization. It is taken by mouth.

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are a class of antidepressant medications used to treat major depressive disorder (MDD), anxiety disorders, social phobia, chronic neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS), and menopausal symptoms. Off-label uses include treatments for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), and migraine prevention. SNRIs are monoamine reuptake inhibitors; specifically, they inhibit the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine. These neurotransmitters are thought to play an important role in mood regulation. SNRIs can be contrasted with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs), which act upon single neurotransmitters.

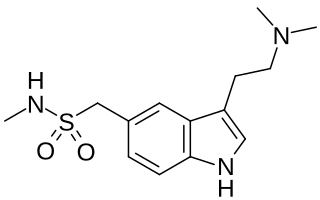

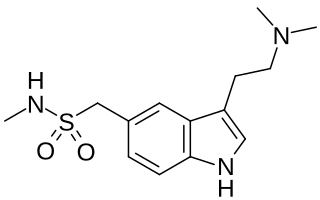

Triptans are a family of tryptamine-based drugs used as abortive medication in the treatment of migraines and cluster headaches. This drug class was first commercially introduced in the 1990s. While effective at treating individual headaches, they do not provide preventive treatment and are not considered a cure. They are not effective for the treatment of tension–type headache, except in persons who also experience migraines. Triptans do not relieve other kinds of pain.

Reboxetine, sold under the brand name Edronax among others, is a drug of the norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (NRI) class, marketed as an antidepressant by Pfizer for use in the treatment of major depression, although it has also been used off-label for panic disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It is approved for use in many countries worldwide, but has not been approved for use in the United States. Although its effectiveness as an antidepressant has been challenged in multiple published reports, its popularity has continued to increase.

Moclobemide, sold under the brand names Amira, Aurorix, Clobemix, Depnil and Manerix among others, is a reversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase A (RIMA) drug primarily used to treat depression and social anxiety. It is not approved for use in the United States, but is approved in other Western countries such as Canada, the UK and Australia. It is produced by affiliates of the Hoffmann–La Roche pharmaceutical company. Initially, Aurorix was also marketed by Roche in South Africa, but was withdrawn after its patent rights expired and Cipla Medpro's Depnil and Pharma Dynamic's Clorix became available at half the cost.

A serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI), also known as a triple reuptake inhibitor (TRI), is a type of drug that acts as a combined reuptake inhibitor of the monoamine neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. It does this by concomitantly inhibiting the serotonin transporter (SERT), norepinephrine transporter (NET), and dopamine transporter (DAT), respectively. Inhibition of the reuptake of these neurotransmitters increases their extracellular concentrations and, therefore, results in an increase in serotonergic, adrenergic, and dopaminergic neurotransmission. The naturally-occurring and potent SNDRI cocaine is widely used recreationally and often illegally for the euphoric effects it produces.

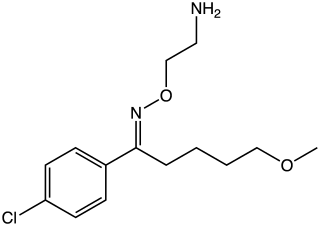

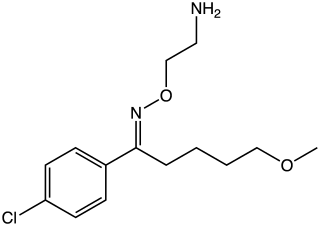

Clovoxamine (INN) is a drug that was discovered in the 1970s and was subsequently investigated as an antidepressant and anxiolytic agent but was never marketed. It acts as a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), with little affinity for the muscarinic acetylcholine, histamine, adrenergic, and serotonin receptors. The compound is structurally related to fluvoxamine.

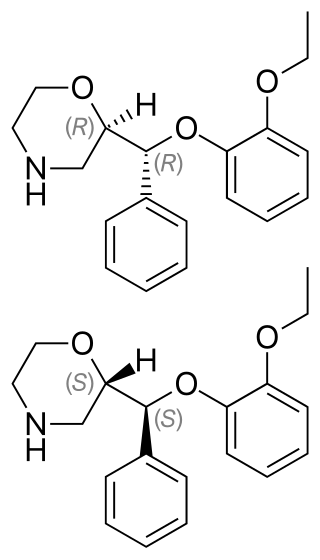

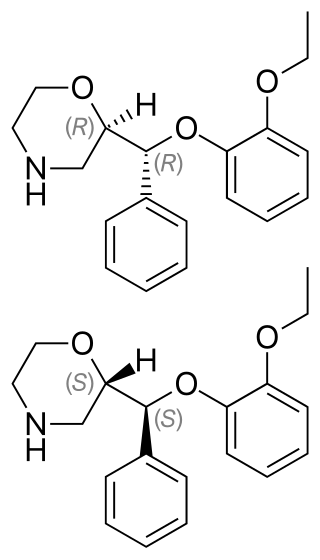

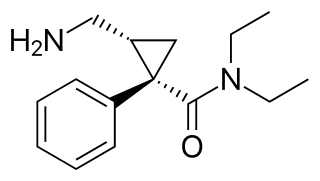

Levomilnacipran is an antidepressant which was approved in the United States in 2013 for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD) in adults. It is the levorotatory enantiomer of milnacipran, and has similar effects and pharmacology, acting as a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a class of drugs that are typically used as antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and other psychological conditions.

Ifoxetine (CGP-15,210-G) is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) which was investigated as an antidepressant in the 1980s but was never marketed. Ifoxetine selectively blocks the reuptake of serotonin in the brain supposedly without affecting it in the periphery. Supporting this claim, ifoxetine was found to be efficacious in clinical trials and was very well tolerated, producing almost no physical side effects or other complaints of significant concern.

Amitifadine is a serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI) or so-called triple reuptake inhibitor (TRI) which is or was being developed by Euthymics Bioscience It was under development for the treatment of major depressive disorder, but in May 2013, it was reported that the drug failed to show superior efficacy to placebo in a phase IIb/IIIa clinical trial. It was suggested that this may have been due to the drug being underdosed. In September 2017, development of amitifadine for the treatment of major depressive disorder was finally officially discontinued. As of September 2017, it is still listed as being under development for the treatment of alcoholism and smoking withdrawal.

The pharmacology of antidepressants is not entirely clear. The earliest and probably most widely accepted scientific theory of antidepressant action is the monoamine hypothesis, which states that depression is due to an imbalance of the monoamine neurotransmitters. It was originally proposed based on the observation that certain hydrazine anti-tuberculosis agents produce antidepressant effects, which was later linked to their inhibitory effects on monoamine oxidase, the enzyme that catalyses the breakdown of the monoamine neurotransmitters. All currently marketed antidepressants have the monoamine hypothesis as their theoretical basis, with the possible exception of agomelatine which acts on a dual melatonergic-serotonergic pathway. Despite the success of the monoamine hypothesis it has a number of limitations: for one, all monoaminergic antidepressants have a delayed onset of action of at least a week; and secondly, there are a sizeable portion (>40%) of depressed patients that do not adequately respond to monoaminergic antidepressants. Further evidence to the contrary of the monoamine hypothesis are the recent findings that a single intravenous infusion with ketamine, an antagonist of the NMDA receptor — a type of glutamate receptor — produces rapid, robust and sustained antidepressant effects. Monoamine precursor depletion also fails to alter mood. To overcome these flaws with the monoamine hypothesis a number of alternative hypotheses have been proposed, including the glutamate, neurogenic, epigenetic, cortisol hypersecretion and inflammatory hypotheses. Another hypothesis that has been proposed which would explain the delay is the hypothesis that monoamines don't directly influence mood, but influence emotional perception biases.