Makassarese, sometimes called Makasar, Makassar, or Macassar, is a language of the Makassarese people, spoken in South Sulawesi province of Indonesia. It is a member of the South Sulawesi group of the Austronesian language family, and thus closely related to, among others, Buginese, also known as Bugis. The areas where Makassarese is spoken include the Gowa, Sinjai, Maros, Takalar, Jeneponto, Bantaeng, Pangkajene and Islands, Bulukumba, and Selayar Islands Regencies, and Makassar. Within the Austronesian language family, Makassarese is part of the South Sulawesi language group, although its vocabulary is considered divergent compared to its closest relatives. In 2000, Makassarese had approximately 2.1 million native speakers.

Vaeakau-Taumako is a Polynesian language spoken in some of the Reef Islands as well as in the Taumako Islands in the Temotu province of Solomon Islands.

The Wariʼ language is the sole remaining vibrant language of the Chapacuran language family of the Brazilian–Bolivian border region of the Amazon. It has about 2,700 speakers, also called Wariʼ, who live along tributaries of the Pacaas Novos river in Western Brazil. The word wariʼ means "we!" in the Wariʼ language and is the term given to the language and tribe by its speakers. Wariʼ is written in the Latin script.

Wintu is a Wintu language which was spoken by the Wintu people of Northern California. It was the northernmost member of the Wintun family of languages. The Wintun family of languages was spoken in the Shasta County, Trinity County, Sacramento River Valley and in adjacent areas up to the Carquinez Strait of San Francisco Bay. Wintun is a branch of the hypothetical Penutian language phylum or stock of languages of western North America, more closely related to four other families of Penutian languages spoken in California: Maiduan, Miwokan, Yokuts, and Costanoan.

The Sasak language is spoken by the Sasak ethnic group, which make up the majority of the population of Lombok, an island in the West Nusa Tenggara province of Indonesia. It is closely related to the Balinese and Sumbawa languages spoken on adjacent islands, and is part of the Austronesian language family. Sasak has no official status; the national language, Indonesian, is the official and literary language in areas where Sasak is spoken.

Sa or Saa language is an Austronesian language spoken in southern Pentecost Island, Vanuatu. It had an estimated 2,500 speakers in the year 2000.

Oroha, categorized as an Austronesian language, is one of many languages spoken by Melanesian people in the Solomon Islands. It is also known as Maramasike, Mara Ma-Siki, Oraha, and Oloha, and is used primarily in the southern part of Malaita Island within the Malaita Province. Little Mala is composed of three indigenous languages of the 'Tolo' people which are Na’oni, Pau, and Oroha. They are all slightly different, yet come from the same origin. The three languages may be thought of as different dialects of the same language. The three Tolo villages now harbor schools under the Melanesian Mission.

Cora is an indigenous language of Mexico of the Uto-Aztecan language family, spoken by approximately 30,000 people. It is spoken by the ethnic group that is widely known as the Cora, but who refer to themselves as Naáyarite. The Cora inhabit the northern sierra of the Mexican state Nayarit which is named after its indigenous inhabitants. A significant portion of Cora speakers have formed an expatriate community along the southwestern part of Colorado in the United States. Cora is a Mesoamerican language and shows many of the traits defining the Mesoamerican Linguistic Area. Under the General Law of Linguistic Rights of the Indigenous Peoples, it is recognized as a "national language", along with 62 other indigenous languages and Spanish which have the same "validity" in Mexico.

Apma is the language of central Pentecost island in Vanuatu. Apma is an Oceanic language. Within Vanuatu it sits between North Vanuatu and Central Vanuatu languages, and combines features of both groups.

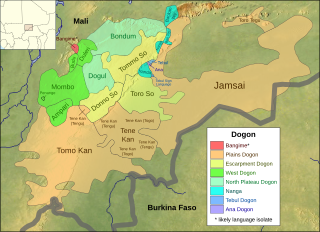

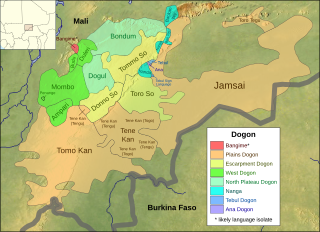

Bangime is a language isolate spoken by 3,500 ethnic Dogon in seven villages in southern Mali, who call themselves the bàŋɡá–ndɛ̀. Bangande is the name of the ethnicity of this community and their population grows at a rate of 2.5% per year. The Bangande consider themselves to be Dogon, but other Dogon people insist they are not. Bangime is an endangered language classified as 6a - Vigorous by Ethnologue. Long known to be highly divergent from the (other) Dogon languages, it was first proposed as a possible isolate by Blench (2005). Heath and Hantgan have hypothesized that the cliffs surrounding the Bangande valley provided isolation of the language as well as safety for Bangande people. Even though Bangime is not closely related to Dogon languages, the Bangande still consider their language to be Dogon. Hantgan and List report that Bangime speakers seem unaware that it is not mutually intelligible with any Dogon language.

The Wuvulu-Aua language is an Austronesian language which is spoken on the Wuvulu and Aua Islands and in the Manus Province of Papua New Guinea.

Abui is a non-Austronesian language of the Alor Archipelago. It is spoken in the central part of Alor Island in Eastern Indonesia, East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) province by the Abui people. The native name in the Takalelang dialect is Abui tanga which literally translates as 'mountain language'.

Moronene is an Austronesian language spoken in Bombana Regency, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia. It belongs to the Bungku–Tolaki branch of the Celebic subgroup.

Kokota is spoken on Santa Isabel Island, which is located in the Solomon Island chain in the Pacific Ocean. Santa Isabel is one of the larger islands in the chain, but it has a very low population density. Kokota is the main language of three villages: Goveo and Sisigā on the North coast, and Hurepelo on the South coast, though there are a few speakers who reside in the capital, Honiara, and elsewhere. The language is classified as a 6b (threatened) on the Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (GIDS). To contextualize '6b', the language is not in immediate danger of extinction since children in the villages are still taught Kokota and speak it at home despite English being the language of the school system. However, Kokota is threatened by another language, Cheke Holo, as speakers of this language move from the west of the island closer to the Kokota-speaking villages. Kokota is one of 37 languages in the Northwestern Solomon Group, and as with other Oceanic languages, it has limited morphological complexity.

Kei is an Austronesian language spoken in a small region of the Moluccas, a province of Indonesia.

The Hawu language is the language of the Savu people of Savu Island in Indonesia and of Raijua Island off the western tip of Savu. Hawu has been referred to by a variety of names such as Havu, Savu, Sabu, Sawu, and is known to outsiders as Savu or Sabu. Hawu belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian language family, and is most closely related to Dhao and the languages of Sumba. Dhao was once considered a dialect of Hawu, but the two languages are not mutually intelligible.

The Savu languages, Hawu and Dhao, are spoken on Savu and Ndao Islands in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia.

Tamashek or Tamasheq is a variety of Tuareg, a Berber macro-language widely spoken by nomadic tribes across North Africa in Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Tamasheq is one of the three main varieties of Tuareg, the others being Tamajaq and Tamahaq.

Nuaulu is a language indigenous to the island of Seram Island in Indonesia, and it is spoken by the Nuaulu people. The language is split into two dialects, a northern and a southern dialect, between which there a communication barrier. The dialect of Nuaulu referred to on this page is the southern dialect, as described in Bolton 1991.

Wamesa is an Austronesian language of Indonesian New Guinea, spoken across the neck of the Doberai Peninsula or Bird's Head. There are currently 5,000–8,000 speakers. While it was historically used as a lingua franca, it is currently considered an under-documented, endangered language. This means that fewer and fewer children have an active command of Wamesa. Instead, Papuan Malay has become increasingly dominant in the area.