Related Research Articles

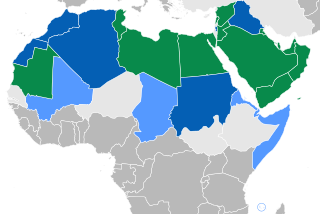

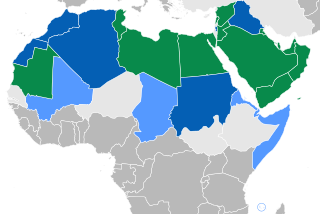

Arabic is a Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The ISO assigns language codes to 32 varieties of Arabic, including its standard form of Literary Arabic, known as Modern Standard Arabic, which is derived from Classical Arabic. This distinction exists primarily among Western linguists; Arabic speakers themselves generally do not distinguish between Modern Standard Arabic and Classical Arabic, but rather refer to both as al-ʿarabiyyatu l-fuṣḥā or simply al-fuṣḥā (اَلْفُصْحَىٰ).

Natives of the Arabian Peninsula, many Qataris are descended from a number of migratory Arab tribes that came to Qatar in the 18th century from mainly the neighboring areas of Nejd and Al-Hasa. Some are descended from Omani tribes. Qatar has about 2.6 million inhabitants as of early 2017, the vast majority of whom live in Doha, the capital. Foreign workers amount to around 88% of the population, the largest of which comprise South Asians, with those from India alone estimated to be around 700,000. Egyptians and Filipinos are the largest non-South Asian migrant group in Qatar. The treatment of these foreign workers has been heavily criticized with conditions suggested to be modern slavery. However the International Labour Organization published report in November 2022 that contained multiple reforms by Qatar for its migrant workers. The reforms included the establishment of the minimum wage, wage protection regulations, improved access for workers to justice, etc. It included data from last 4 years of progress in workers conditions of Qatar. The report also revealed that the freedom to change jobs was initiated, implementation of Occupational safety and health & labor inspection, and also the required effort from the nation's side.

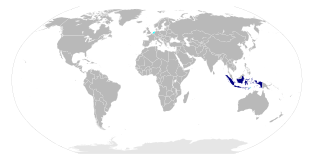

Indonesian is the official and national language of Indonesia. It is a standardized variety of Malay, an Austronesian language that has been used as a lingua franca in the multilingual Indonesian archipelago for centuries. With over 280 million inhabitants, Indonesia ranks as the fourth most populous nation globally. According to the 2020 census, over 97% of Indonesians are fluent in Indonesian, making it the largest language by number of speakers in Southeast Asia and one of the most widely spoken languages in the world. Indonesian vocabulary has been influenced by various regional languages such as Javanese, Sundanese, Minangkabau, Balinese, Banjarese, and Buginese, as well as by foreign languages such as Arabic, Dutch, Portuguese, and English. Many borrowed words have been adapted to fit the phonetic and grammatical rules of Indonesian, enriching the language and reflecting Indonesia's diverse linguistic heritage.

Malay is an Austronesian language that is an official language of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, and that is also spoken in East Timor and parts of Thailand. Altogether, it is spoken by 290 million people across Maritime Southeast Asia.

Javanese is a Malayo-Polynesian language spoken by the Javanese people from the central and eastern parts of the island of Java, Indonesia. There are also pockets of Javanese speakers on the northern coast of western Java. It is the native language of more than 68 million people.

The Javanese are an Austronesian ethnic group native to the central and eastern part of the Indonesian island of Java. With more than 100 million people, Javanese people are the largest ethnic group in both Indonesia and in Southeast Asia as a whole. Their native language is Javanese, it is the largest of the Austronesian languages in number of native speakers and also the largest regional language in Southeast Asia. As the largest ethnic group in the region, the Javanese have historically dominated the social, political, and cultural landscape of both Indonesia and Southeast Asia.

In addition to its classical and modern literary form, Malay had various regional dialects established after the rise of the Srivijaya empire in Sumatra, Indonesia. Also, Malay spread through interethnic contact and trade across the south East Asia Archipelago as far as the Philippines. That contact resulted in a lingua franca that was called Bazaar Malay or low Malay and in Malay Melayu Pasar. It is generally believed that Bazaar Malay was a pidgin, influenced by contact among Malay, Hokkien, Portuguese, and Dutch traders.

In sociolinguistics, a sociolect is a form of language or a set of lexical items used by a socioeconomic class, profession, age group, or other social group.

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) or Modern Written Arabic (MWA) is the variety of standardized, literary Arabic that developed in the Arab world in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and in some usages also the variety of spoken Arabic that approximates this written standard. MSA is the language used in literature, academia, print and mass media, law and legislation, though it is generally not spoken as a first language, similar to Contemporary Latin. It is a pluricentric standard language taught throughout the Arab world in formal education, differing significantly from many vernacular varieties of Arabic that are commonly spoken as mother tongues in the area; these are only partially mutually intelligible with both MSA and with each other depending on their proximity in the Arabic dialect continuum.

The Cirebon or Cirebonese are an indigenous ethnic group native to Cirebon in the northeastern region of West Java Province of Indonesia. With a population of approximately 2 million, the Cirebonese population are mainly adherents of Sunni Islam. Their native language is Cirebonese, which combines elements of both Javanese and Sundanese, but with a heavier influence from Javanese.

Betawi, also known as Betawi Malay, Jakartan Malay, or Batavian Malay, is the spoken language of the Betawi people in Jakarta, Indonesia. It is the native language of perhaps 5 million people; a precise number is difficult to determine due to the vague use of the name.

There are 1,340 recognised ethnic groups in Indonesia, making it one of the most diverse countries in the world. The vast majority of those belong to the Austronesian peoples, with a sizeable minority being Melanesians. Indonesia has the world's largest number of Austronesians and Melanesians.

Communication accommodation theory (CAT) is a theory of communication, developed by Howard Giles, concerning "(1) the behavioral changes that people make to attune their communication to their partner, (2) the extent to which people perceive their partner as appropriately attuning to them". This concept was later applied to the field of sociolinguistics, in which linguistic accommodation or simply accommodation is the process of individuals adapting their style of speaking to become more like the style of their conversational partners.

Javanese culture is the culture of the Javanese people. Javanese culture is centered in the provinces of Central Java, Yogyakarta and East Java in Indonesia. Due to various migrations, it can also be found in other parts of the world, such as Suriname, the broader Indonesian archipelago region, Cape Malay, Malaysia, Singapore, Netherlands and other countries. The migrants bring with them various aspects of Javanese cultures such as Gamelan music, traditional dances and art of Wayang kulit shadow play.

Palembang, also known as Palembang Malay, is a Malayic variety of the Musi dialect chain primarily spoken in the city of Palembang and nearby lowlands, and also as a lingua franca throughout South Sumatra. Since parts of the region used to be under direct Javanese rule for quite a long time, Palembang is significantly influenced by Javanese, down to its core vocabularies.

Varieties of Arabic are the linguistic systems that Arabic speakers speak natively. Arabic is a Semitic language within the Afroasiatic family that originated in the Arabian Peninsula. There are considerable variations from region to region, with degrees of mutual intelligibility that are often related to geographical distance and some that are mutually unintelligible. Many aspects of the variability attested to in these modern variants can be found in the ancient Arabic dialects in the peninsula. Likewise, many of the features that characterize the various modern variants can be attributed to the original settler dialects as well as local native languages and dialects. Some organizations, such as SIL International, consider these approximately 30 different varieties to be separate languages, while others, such as the Library of Congress, consider them all to be dialects of Arabic.

Indonesia–Madagascar relations spans for over a millennium, since the ancestors of the people of Madagascar sailed across the Indian Ocean from the Nusantara Archipelago back in 8th or 9th century AD. Indonesia has an embassy in Antananarivo, while Madagascar does not have an accreditation to Indonesia. It was announced in December 2017 that Madagascar would be opening an embassy in Jakarta in 2018, however, the embassy was never opened.

There have been a number of Arabic-based pidgins and creoles throughout history, including a number of new ones emerging today. These may be broadly divided into the Sudanic pidgins and creoles, which share a common ancestry, and incipient immigrant pidgins. Additionally, Maridi Arabic may have been an 11th-century pidgin.

Indonesian Arabic is a variety of Arabic spoken in Indonesia. It is primarily spoken by people of Arab descents and by students (santri) who study Arabic at Islamic educational institutions or pesantren. This language generally incorporates loanwords from regional Indonesian languages in its usage, reflecting the areas where it is spoken.

References

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, p. 109.

- 1 2 3 Azzuhri 2016, p. 114.

- 1 2 Sholihatin 2008, p. 18.

- ↑ Sholihatin 2008, p. 57.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, p. 108.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, p. 110.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Kinasih 2013, p. 41.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, p. 113.

- ↑ Kinasih 2013, p. 39.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Sholihatin 2008, p. 19.

- ↑ Kinasih 2013, p. 43.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, p. 128.

- ↑ Kinasih 2013, p. 52.

- ↑ Kinasih 2013, pp. 42–49.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, p. 116.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, pp. 116–118.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, p. 123.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, p. 125.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Azzuhri 2016, p. 126.